The years 1858 to 1939 form the foundations of and add historic and cultural depth to the current India-Japan bilateral relationship. These engagements during the colonial period are well-documented and within living memory, unlike the ancient shared Buddhist past of both nations. The tangible milestones of these booming trade ties can be found in Japanese and Indian corporate histories, and historic sites in the city of Bombay (now Mumbai).

The enormous carrying trade in raw cotton and yarn[1] from Bombay port to the Japanese ports like Kobe and to a lesser extent Yokohama, was the foundation of Japan’s ‘First Industrial Revolution’ which began with its textile mill industry and its ancillary manufacturing and services sectors, like banking, insurance, and shipping.[2] Bombay and its twin city of Karachi, part of the Presidency of Bombay, were key ports for the export of Indian cotton to Japan. By 1935-36, Japanese cloth imports into India surpassed Great Britain’s. These ties, India-Japan’s co-dependency in the pre-Second World War era, was later revived in the 1960s with Indian iron ore exports playing a critical role in the high-growth, heavy industries strategy adopted by post-war Japan.

The port of Bombay and its markets played an important role in anchoring the pre-1945 trade and commerce between India and Japan. Bombay city was a major hub for the export of Indian yarn and cotton to Japan. From the 1890s, short-staple Deccan cotton from the city’s hinterland was the main commodity of export from Bombay, and colourfully printed cheaply-priced Japanese textiles were the main imports by the 1920s, rivalling both local and British mill-made textiles. It was around this trade that an entire ecosystem of Japanese trading firms, two shipping companies, banks, and the Association of Japanese Cotton Buyers was established in the city.

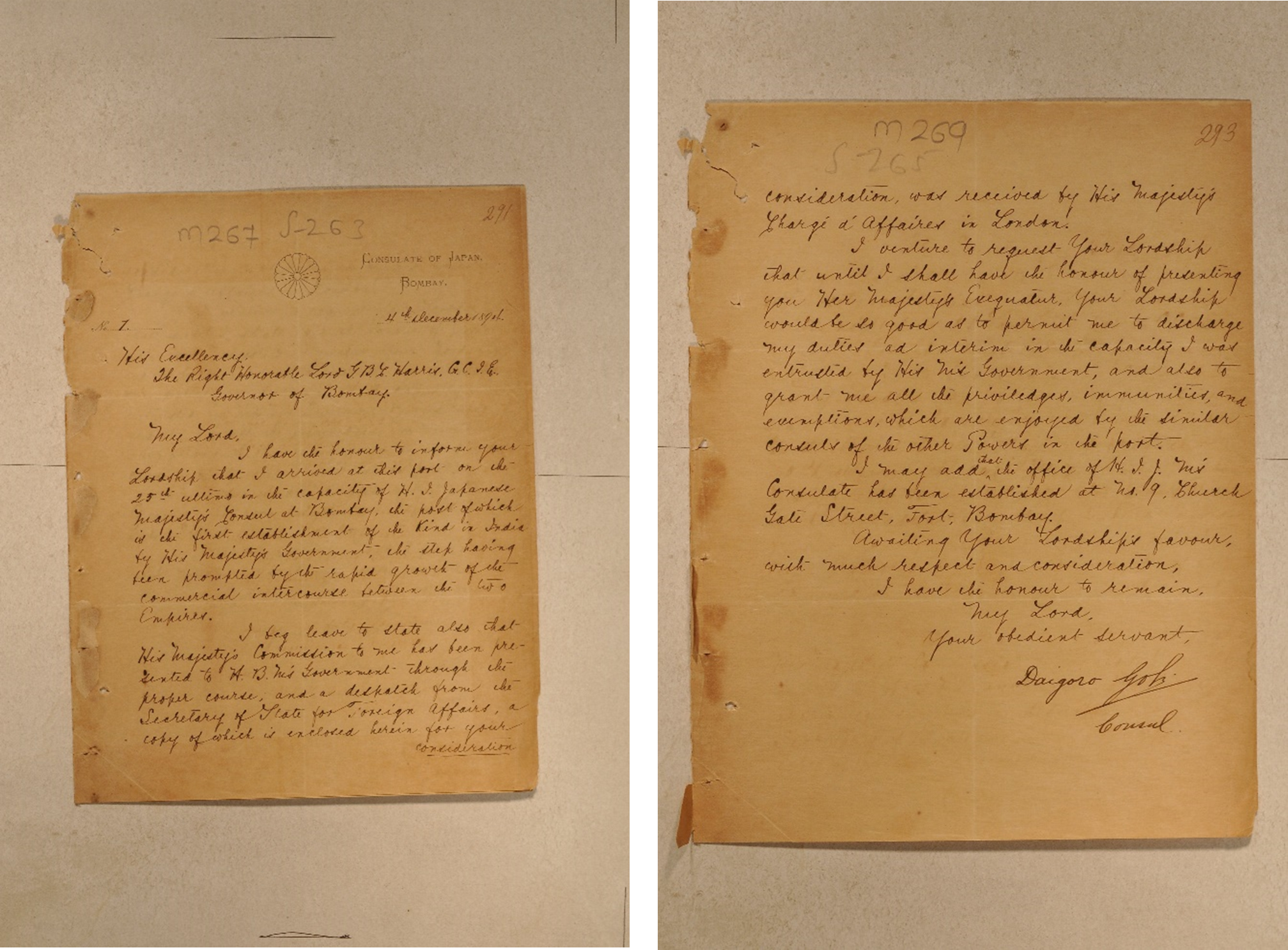

The 1890s saw the entry of big Japanese firms like Mitsui Busan (Mitsui Trading Company) in 1893,[3] who began carrying a greater part of this trade from the period just before the First World War (1914 to 1918). This was followed the next year by the establishment of Japan’s first official mission[4][5] in India headed by Consul Dargoro Goh. In that same year – 1894, the Yokohama Specie Bank (YSB) opened its first agency (it became a branch in 1900) in the city.[6]

The 1890s was also a time when increasing amounts of raw (ginned) cotton as against cotton yarn from Bombay’s mills, was being exported to Japan. This shift was due to the growth in the number of Japanese spinning mills, the first of which was the Osaka Spinning Mill (1888), which began producing superior yarn compared to foreign imports for Japan’s textile mills centered in Kobe-Osaka. By the early 20th century, it was evident that Japanese mills enjoyed a marked advantage. This derived from a combination of higher labour productivity, low cost of raw material, finer counts of cloth due to indigenous improvements in textile technology, the rationalization of the textile industry from 1921, and a currency weighed in its favour because of the conterminous events of devaluation of the Yen and Japan going off the Gold Standard in 1931 to peg its currency to the British pound.[7]

The Indian Rupee in contrast was artificially kept high by the India Office at one pound six deuce because it was advantageous to Great Britain. This impacted India’s industrialization and encouraged cheap (Japanese) exports.[8] This was a turning point, as now Japan began looking to India and the South and Southeast Asian markets to sell its enormous surplus of finished cloth.

In Bombay, the cotton purchases of Japanese trading firms like Mitsui, Nippon Menka Kabushiki Kaisha (Japan Cotton Trading Co. Ltd.)[9], Gosho Kabushiki Kaisha Ltd., Toyo Menka Kaisha Ltd., were financed by a mix of foreign chartered banks (led by HSBC) and Japanese banks (largely YSB), who worked with the Bank of Bombay’s rural branches and even native shroffs (bankers) in the cotton hinterland.

When Japan’s trade with Bombay began in the mid-19th century, Japanese buyers contracted for their cotton consignments through foreign trading houses[10] like Rallis and Volkart but soon ventured into the cotton-growing areas themselves to contract for the crop directly with farmers.[11] Of special note are the three San-men: Toyo Menka (separated from Mitsui Busan in March 1920), Nihon Menka and Gosho firms who by 1918-19 had a mix of Japanese and Indian employees who went into the cotton-growing regions of what is in today’s Gujarat, central Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Punjab, to buy and have the raw cotton ginned (cleaned) and baled, and then transported to the city for shipping to Japan. In the case of Toyo Menka, who began direct purchases from 1907, direct purchases constituted 84.3% of Mitsui’s purchases by 1918.[12]

The direct purchase process which lasted till about 1934-35 for Toyo Menka, had begun declining from 1924-25 because of competition in the hinterland from a group of Bombay broker-buyers known as Jettawalas who also ventured into the hinterland to make their purchases.[13] Moreover, the success of direct purchases hinged on the agreements between the trading firm sourcing the cotton and the big spinning mills in Japan. The agreements between the San-men and their buyers, the mills, diminished during the First World War, after which the mills began looking to international markets for their purchases which were made year-round.

However, while it lasted, it involved a mix of financial instruments to underwrite it that ranged from forward contracts or Sutta from the Japanese mills, letters of credit issued by banks, bills of exchange, and even the local Hundis were used to facilitate the cotton trade as purchases from farmers had to be made in the Indian silver rupee.

It appears that these firms conducted the inland purchases for the Japanese firms in Bombay. An indication of the size of this trade in 1913 is evident from the Yen value of the size of exports from India as compared to that from China, which was Yen 148,082,178 and Yen 16, 205, 545 respectively.[14] More importantly, in 1922-23 they dealt with 30% of India’s cotton exports and even began selling it in Europe and China.

Parallel to the slow decline in raw cotton purchases by Japanese trading houses was the increase in the imports of Japanese textiles into India. The rationalization of the Japanese cotton industry, beginning in the mid-1920s, was followed by a devaluation of the Japanese Yen after Japan abandoned the gold standard in December 1932 and pegged its currency to the pound sterling. These factors, amongst others like higher labour productivity and an artificially high Indian rupee, made Japanese textiles extremely competitive compared to Indian and British ones despite the increasing import tariff on them by the British Indian government. By early 1933, the tariff on non-British cotton goods was 50% compared to 25% on British ones. In June 1933, this duty was raised from 50% to 75%, resulting in a boycott of Indian raw cotton by Japanese industrialists from July to December 1933. This trade war resulted in the first Indo-Japanese trade negotiations, which began in September 1933 and was formally concluded in early January 1934.[15]

The main pivot of both the first and the second Indo-Japanese commercial treaties is that both were based on barter. In the first treaty, Japan could export a full quota of 400 million yards of textiles[16] only if it imported 1.5 million bales of cotton in return, thereby linking the quantum of exports to imports of raw cotton from India. The import tariff on non-British textiles was now stabilized between 40-50%. The Second Treaty was concluded in March 1937.

This robust Bombay-Japan trade from the 1890s ensured an active circulation of people between the two countries, which naturally expanded into the cultural, political, and religious realms to forge memories between the city and Japan. These social, religious, and cultural confluences were snapped during the period of the Second World War and never recovered thereafter. Studies on economic-social-cultural-religious ties must therefore be rooted in the geo economic and geopolitical situations which not only brought the two nations together, but also disrupted relations during 1939 to 1952[17] because of British India being a colony of Great Britain.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History at Gateway House.

This an excerpt from the chapter titled ‘Japan in Bombay and its presidency: trade, community, and the Japan Buddha Order (19th to mid-20th century)’ which appears in the book, ‘Geographies of Exchange between India and Japan’ edited by Sushila Narasimhan and Parul Bakshi, published by Manak Publications Pvt. Ltd (2024).

It is republished here with permission.

References

[1] Cotton yarn was initially the main export till Japan began setting up its own spinning mills. The first spinning mill in Japan was the Osaka Spinning Mill established in 1888. Later ginned cotton formed the bulk of exports from India, alongside Chinese and American cotton, all feeding into the Japanese spinning and weaving industry.

[2] Tikekar, A. 1994a. A Century of Ties Bombay and Japan. 1st ed. Bombay: The Consulate General of Japan in Bombay, pp.11–12.

[3] One should not confuse the current Mitsui & Co. Ltd. India, as being a continuation of the old Mitsui & Co. in British Bombay, as legally both firms are separate entities. The old Mitsui opened its office in Bombay in 1893 and was located at 193, Hornby Road, originally known as the Dwarkadas building, which is today’s Kitab Mahal. However, after the war in 1951 the current Mitsui & Co. opened offices in the city as a new legal entity.

[4] Consul Goh in his letter of introduction to the Governor of Bombay on 4 December, stated that the Consulate was located at 9 Churchgate Street (Fort).

[5] Tikekar,1994:11-12.

[6] Nishimura, Shizuya, Toshio Suzuki, and Ranald Michie, eds., 2012. The Origins of International Banking in Asia: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, p.181.

[7] Choi, Chi-Cheung, Tomoko Shiroyama, and Takashi Oishi. 2019. Chinese and Indian merchants in modern Asia networking businesses and the formation of a regional economy. Leiden Boston Brill, p.231.

[8] Choi, Chi-Cheung, Takashi Oishi and Tomoko Shiroyama. 2019. Chinese and Indian Merchants in Modern Asia. BRILL, p.234.

[9] Nippon Menka Kabushiki Kaisha was headquartered in Osaka. The Bombay office was located in Nippon Building on Outram Road.

[10] These were the agency houses that provided a wide spectrum of commercial services for their clients. They had rural networks that facilitated the purchase of commodities by using local brokers and native bankers.

[11] Tikekar, 1994:11.

[12] Kagotani, N. 2013. Chapter 11 ‘Up-country Purchase Activity of Indian Raw Cotton by Toyo Menka’s Bombay Branch 1896-1935’ in Commercial Networks in Modern Asia. Routledge.

[13] Kagotani, 2013:209.

[14] Nishimura, Shizuya, Toshio Suzuki and Ranald Michie. 2012. The origins of international banking in Asia: the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.186.

[15] Choi, Chi-Cheung, Takashi Oishi and Tomoko Shiroyama. 2019. Chinese and Indian Merchants in Modern Asia. BRILL, pp. 231-33, 247.

[16] This yardage was further broken down into quotas for different categories like Grays, Bordered Grays, Bleached, Prints, Coloured or Dyed, and Woven fabrics.

[17] The year 1952 is when the Japanese Consulate in Bombay was re-established. Although in 1948, the first trade mission from Japan had arrived in Bombay to restart trade in cotton between the two countries.