The Oval Office’s new occupant will soon be known, but regardless of the election’s outcome, the India-United States Strategic Partnership across 51 bilateral areas of common interest, of which defence and trade are foremost, will continue to be a reality in the foreseeable future[1].

The changing geopolitics in the Indian Ocean with a militarily assertive China, a sluggish U.S. economy in search of markets, a dynamic, highly skilled Indian American diaspora make the India-U.S. partnership a perfect fit. An added bonus is their shared political ideology of constitutional democracy.

These commonalities have emerged rather more recently compared to the 200-year-old business, cultural and people-to-people connections between the Indian subcontinent and the U.S., which, in the late 18th century, was centred on the port cities of Calcutta and Bombay, and to a lesser extent, Madras.

It was trade mainly that yoked Bombay and America together whereas the country’s Calcutta connections were far more nuanced and diverse, encompassing culture and religion, such as the influence of the Brahmo Samaj movement on American transcendentalism[2] of the early 19th century.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

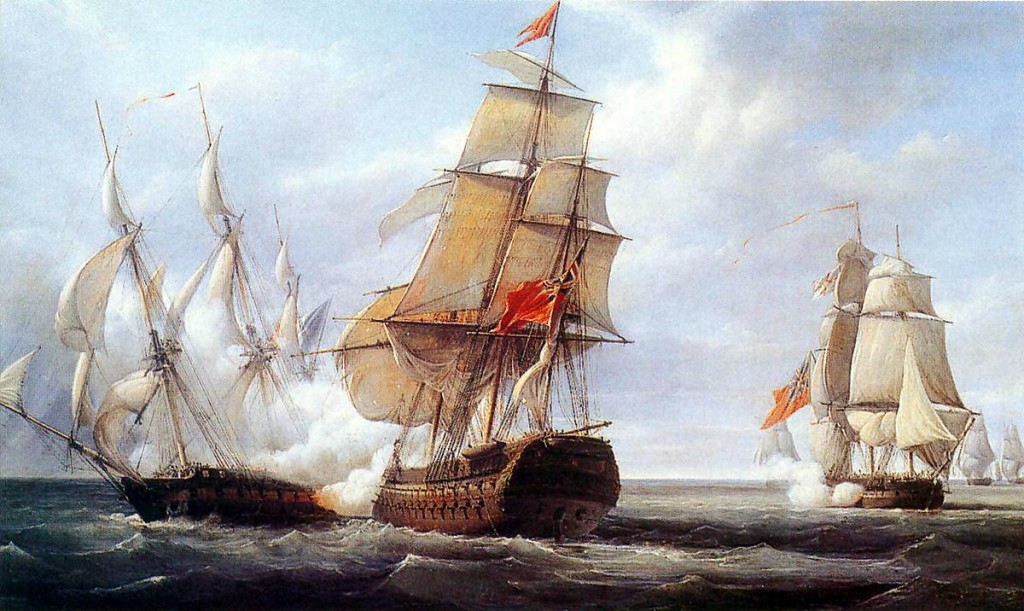

Early American trade

American trade with the Indian subcontinent began after the American War of Independence (1775-1783) and the Treaty of Paris (1783) between Britain and its former 13 American colonies, which resulted in the bestowing of most-favoured-nation status (MFN) to the country. This meant that theAmericans were now ‘free traders’ who could sail into any British colonial port in spite of the English East India Company’s monopoly over trade with both India and China. This had prevented private British traders from entering these markets till the Company’s monopoly over Indian trade ended in 1813 and over the China segment in 1833.

The nifty American clippers (ships of 400 to 600 tonnes), with their small crew and supercargo or business manager, were initially welcomed at British colonial ports, particularly Bombay and Surat[3], where they brought in huge amounts of silver specie (coins) in the early years in exchange for Surat piece goods (cloth). This silver was what the Company used to pay for its China trade and its mint at Bombay. For example in 1804, American imports into these two ports were made up of sicca rupee[4] 2, 07, 564 of treasure, but only sicca rupee 9,071 of merchandise[5].

The balance of trade began changing almost imperceptibly in favour of the Americans. Each voyage generated profits, with a clipper spending an average of one to three years, out on the Indian Ocean, laying anchor at port after port: 20% or more of the proceeds had to go to the investors.

America’s first millionaire, Elias Haskett Derby, who made a fortune trading in Deccan cotton, sourced from Bombay, serves as illustration. It was during the second voyage of his clipper, ‘Grand Turk’, in 1787-88, that his son, Elias Haskett Derby Jr., in his capacity as supercargo, returned with a cargo of Deccan, short-staple cotton from Bombay. The Derbys tried to sell this in Salem, but were unsuccessful. This was the first cargo of Deccan cotton to arrive in the United States, which was then made up of only 13 states.

Instead of disposing of this cotton at a loss, Derby Sr. sent it on to Canton (Guangzhou), where there was an established market for Deccan cotton. Now, having stumbled on the valuable country trade in Deccan cotton from Bombay to Canton, he backed this up by purchasing more raw cotton at Bombay and sending it directly to Canton, where he exchanged it for Chinese tea and silks. These, in turn, along with Indian goods, like indigo, ginger, and saltpetre (potassium nitrate used in gunpowder), were sold at various ports in Europe, in the Caribbean, and South America, as the American market was too small to absorb the volume of this trade.

Simultaneously, the Americans’ import of silver specie into Bombay almost stopped by the first decade of the 19th century as goods that they brought in, such as brandy, claret and port wine; metals; cordage, oil and sugar, generated for them the money to buy cotton, and later Malwa opium, in Bombay, for the China market.

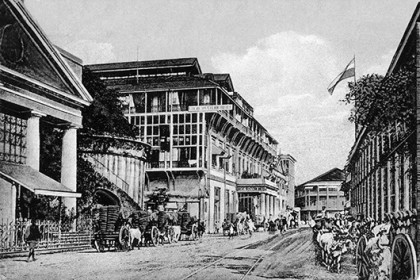

Image courtesy: Eminence Designs Pvt Ltd. Bombay The Cities Within (1995)

Frederick Tudor – ice man from Boston

The American merchants were constantly on the look out for saleable merchandise, and ballast for the clippers, that were setting out of the ports of Salem, Newburyport, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Castle, to the East. Wish fulfilment came when Boston businessman Frederick Tudor devised a way to transport large blocks of ice across the Atlantic into the Indian Ocean ports of Calcutta in 1833, and Bombay in 1834.

The blocks, which were cut from the frozen ponds of Boston and its vicinity, were insulated with pine dust and wrapped in felt. Further, the holds of the clippers themselves were insulated to ensure that at least three-fourths of it reached the various destinations.

In Bombay, the recipient of the first consignment of ice was Jehangir Nusserwanjee Wadia, the son of Nusserwanjee Maneckjee Wadia, a merchant who transacted all the American business in the city. The Wadias belonged to the famous Bombay ship-builder family that was responsible for building the Royal Navy warship, HMS Minden, aboard which the American national anthem—‘The Star-Spangled Banner’–was composed by poet Francis Scott Key, while being held prisoner on board during the 1812 British-American war.

That first consignment of ice created quite a stir in the city,it being allowed to bypass customs . It was unloaded at night to prevent melting, and its consumption (as reported by the Gujarati newspaper Bombay Samachar) at a party hosted by Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, merchant and philanthropist, resulted in the host and his guests coming down with a cold the next day[6].

This did not dampen the enthusiasm for American ice in the city, with an ice committee being setup to supervise its storage and distribution, and an ice house being built in 1843 outside the Naval Dockyard gate at the same spot where the K.R. Cama Oriental Institute now stands.

The ice trade ended in the 1880s, with ice factories being set up in Bombay. In a sense, it marked the transition of American trade–from its early years, when it enjoyed MFN status–to when tariff barriers were set up by both sides to protect a nascent American and Bombay cotton mill industry.

The comprehensive U.S.-India Strategic Partnership, though it doesn’t do away with tariffs, will re-energise this important historic relationship.

Sifra Lentin is the Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2016 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References:

[1] Embassy of India, Washington D.C., USA, Brief on India-U.S. Relations https://www.indianembassy.org/pages.php?id=41 (Accessed on 23 October 2016)

[2] Transcendentalism is a philosophical and social movement, which developed in New England (an area comprising the states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island) around 1836 in reaction to rationalism.

[3] The formal title was ‘The Treaty of Amity, Commerce & Navigation between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America’

[4] The Sicca rupee is the currency that circulated in Bengal Presidency. At this point in time each of the three presidencies (Bengal, Bombay, and Madras) had their own currency and currency circle.

[5] Milburn, William, ‘Oriental commerce; containing a geographical description of the principal places in East Indies, China, and Japan, with their produce, manufactures, and trade Volume 1’ (London, Black, Parry & co, 1813), p 201.

[6] Dwivedi, Sharada, and Rahul Mehrotra, Bombay: The Cities Within (Bombay, India Book House Pvt Ltd., 1995), p 33.