Who is the master that finance serves? Does finance know? The Great Financial Crisis[1] (GFC) revealed enormous flaws, short-sightedness and the lack of a clear moral compass. The search for profit is the global financial system’s most powerful driver but, even after the cleaning of the fiasco (a good chunk of it, at taxpayers’ expense), benefits to stockholders have not been particularly rewarding. Financial stocks do not now command the sky high price-earnings multiples of the past. They are frequently relegated to the bottom of the pack.[2] And the true stress test on risk and returns will only come when the next recession hits the road.

Regulations, such as Basel III, Dodd & Frank and the macroprudential paraphernalia, have increased, but the extra burden has not brought an improved sense of safety. (Lower P/E ratios are a way to protect from higher perceived risk.) So, a second easy question is due: is more finance, good or bad?[3] At the end of the day, could it trigger another unforeseen potentially lethal meltdown? Who can assure the answer is a strong no? Ironically, no other industry relies more on trust than finance.

The time is therefore ripe for sustainable finance,[4] for responsible investment.[5] Responsible investment’s aim is to integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into investment decisions. A sensitivity to sustainability apart, there are strong business reasons too to do so.

In terms of climate change, 17 of the 18 warmest years in the 136-year record between 1884 and 2017 have all occurred since 2001, with the exception of 1998.[6] The frequency of extreme weather events causing $1 billion or more in losses has risen sharply over the past decade.[7] Conventional finance does not take into account events such as floods, hurricanes and the consequent infrastructure destruction. Even central banks acknowledged that the topic falls within their mandates[8]— not just for reasons of financial stability, but also due to its potential consequences for the formulation and designing of monetary policy[9].

A lack of attention to social impact has incurred some high costs, especially in the long run. The GFC sabotaged the social contract, and a decade later, the payback is the eruption of social and political divides that increasingly threaten the very foundations of economic and political national regimes (and by doing so, the established cooperative international order). As for governance, it was a huge mess behind the scenes in the genesis of the GFC—perhaps with the tacit complicity of insiders and participants, but was severely underestimated within the conventional radar. It is clear then that ESG risks do matter for business, and are likely to intensify in the coming years.

The essential idea of sustainable finance is to integrate ESG factors into mainstream finance. The rationale for companies to adopt such a modus operandi is that they may have made a cash outlay, analysed the projected net cash flow and found everything in ostensible order, but then later, discover quite other factors influencing the expected profits, such as environmental restrictions, product liability and losses due to very poor governance. All three strictly non-financial factors play a material role in determining risk and return, and if well-calibrated, could contribute to better manage risk and generate sustainable, long-term results.

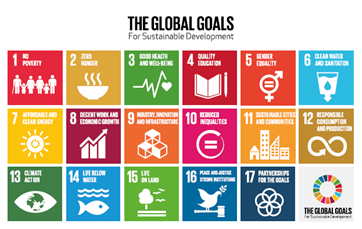

The globally agreed framework for sustainability are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),[10], launched by the United Nations in 2015 after approval by “all the countries of the world”.[11] The SDGs aim to create a viable model for the future in which “all economic growth is achieved without compromising our environment or placing unfair burdens on societies”.[12] In that knowledge, the Principles of Responsible Investing (PRI)[13] were set to align finance with the “broader objectives of society”.[14] In fact, lining up the global financial system with the SDGs might not only achieve a better risk/reward performance, but provide a set of societal values and norms consistent with beliefs, and with them, a sense of purpose. With a sustainable anchor, and the goals of society as its master, a trustworthy financial system could reemerge.

The SDGs “are the right response to the great challenges of the 21st century, the right antidote to the loss of trust in institutions of all kinds, and, in some countries, the loss of faith in global cooperation,”[15] Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the IMF, has said. The SDGs are down-to-earth objectives, such as ending poverty and hunger and ensuring clean water and sanitation. They are not meant to benefit the few at the top of the income ladder, but to cover basic needs and help create an inclusive social fabric.

The SDGs set an extraordinarily ambitious agenda: the UN Commission on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that meeting the SDGs will require $5 trillion to $7 trillion in investment each year from 2015 to 2030.[16] That will be impossible to reach without private sector engagement.[17] The good news is that the private sector is deeply interested in participating.[18] The financial system will, therefore, have to find ways of creating (and re-orienting) investment flows towards the new innovative products and services that are needed to achieve the SDGs. By taking SDGs and their targets as benchmarks, it is even possible to measure the real world impact of corporate and financial decisions and efforts.[19]

China´s presidency of the G20 brought green finance[20] decisively into the G20 agenda by setting a special dedicated study group[21] in 2016. Under Argentina´s presidency two years later, members decided to widen the scope of that stream of work by replacing it with the Sustainable Finance[22] Study Group (SFSG). The SFSG addressed specific sustainability-related challenges in three areas: creating sustainable assets for capital markets; developing sustainable Private Equity and Venture Capital (PE/VC); and exploring potential applications of digital technologies to sustainable finance, taking into account specific countries’ circumstances, priorities and needs.[23]

The task does not end here. A well-aligned financial system might provide the muscle for a greater enterprise: a new sustainable capitalism. Sustainable finance is not charity, but the pursuit of well-grounded profits (with an inter-generational perspective).

Capitalism has proved its extraordinary capacity to promote strong growth. Aligning capitalism to the larger scheme of things is the logical next step.

BOX 1: THE SDGs

BOX 2: THE PRINCIPLES OF RESPONSIBLE INVESTING (PRI)

José Siaba Serrate is Counselor Member, The Argentine Counsel of International Relations (CARI).

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] The GFC triggered the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

[2] Within the eleven sectors that comprise the S&P 500 index, financial stocks 12 month forward price-earnings (p/e) multiple is ranked the lowest (at 10.2 times earnings) as of year end 2018. Their 5 year average p/e multiple (13.1) is the second lowest sectoral level while their 10 year average p/e multiple (12.5) is the lowest.

Source: Factset Earnings Insight Report, 21 December 2018.

[3] Interestingly, Stephen Cechetti and Ennise Kharroubi, found evidence that financial booms are not growth enhancing – and that evidence plus the GFC experience– made them conclude that “there is a pressing need to reassess the relationship of finance and real growth in modern economic systems”. Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth?, BIS Working Paper 490, February 2015. For a more encouraging view on emerging markets’ financial systems, see Ratna Sahay et al, Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets, IMF Staff Discussion Note, May 2015.

[4] José Siaba Serrate, “Why sustainable finance makes financial sense (in spanish)”, Revista del Instituto Argentino de Ejecutivos de Finanzas, Number 255, December 2018.

[5] What is responsible investing? <https://www.unpri.org/pri/what-is-responsible-investment>

[6] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Global Temperature, (Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration), <https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/>

[7] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Adapting Portfolios for Climate Change, BlackRock Investment Institute Global Insights, September 2016.

[8] “Climate-related risks are a source of financial risk and fall within the supervisory and financial stability mandates of Central Banks and Supervisors”. Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) First Progress Report, October 2018. The NGFS is is a group of 18 Central Banks and Supervisors and

5 international organizations.

[9] “The global financial crisis has shown that extreme events can quickly erode central banks’ conventional policy space. Catastrophic climate change could thus test the limits of how far monetary policy can go and, in the extreme, force us to rethink our current policy framework.”, Speech by Benoît Cœuré, at a conference on “Scaling up Green Finance: The Role of Central Banks”, Berlin, 8 November 2018.

[10] The sustainability agenda covers three broad areas – economic, social and environmental development –comprising 17 global goals, further developed in 169 targets, to be reached by 2030.

[11] They were approved by all 193 UN member countries. Unlike other initiatives, for example, those from the G20, they lack legitimacy concerns.

[12] Principles for Responsible Investment, The SDG Investment Case, <https://www.unpri.org/sdgs/the-sdg-investment-case/303.article>

[13] The PRI were launched by the UN in 2006.

[14] The preamble to the Principles says:“We recognise that applying these Principles may better align investors with broader objectives of society” and “The PRI acts in the long-term interests of its signatories, of the financial markets and economies in which they operate and ultimately of the environment and society as a whole.” www.unpri.org

[15] Lagarde, Christine, ‘The Helen Alexander Lecture: The Case for the Sustainable Development Goals’, 17 September 2018, <https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2018/09/17/sp09172018-the-case-for-the-sustainable-development-goals>

[16] Principles for Responsible Investment, The SDG Investment Case, <https://www.unpri.org/sdgs/the-sdg-investment-case/303.article>

[17] “We estimate that it will take roughly 4 trillion dollars per year to achieve the SDGs, but official development assistance is only about 140 billion dollars per year. To achieve the global goals, we need the private sector—and institutional investors in particular” according to World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim.

The World Bank, Incorporating Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) Factors Into Fixed Income Investments, (Washington, D.C.: The World Bank), <http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/04/19/incorporating-environment-social-and-governance-esg-factors-into-fixed-income-investment>

[18] At the start of 2016, there were $22.89 trillion of assets being professionally managed under responsible investment strategies. In relative terms, responsible investment stood at 26 percent of all professionally managed assets globally. Not a bad starting point, though strategies and metrics should be improved to have significant impact. 2016 GSIA Global Investment Review.

[19] “Embracing the relationship with society, the environment and government creates a new strategic lens through which to view and judge business success.”

Principles for Responsible Investment, The SDG Investment Case, <https://www.unpri.org/sdgs/the-sdg-investment-case/303.article>

[20] Green finance is defined as finance that delivers environmental benefits in the context of sustainable development.

United Nations Environment Programme, Leading Financial Centres Gather to Boost Sustainable Finance, (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme), <https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/press-release/leading-financial-centres-gather-boost-sustainable-finance>

[21] The proposal to launch the Green Finance Study Group was adopted by the G20 Finance and Central Bank Deputies meeting on 15 December 2015 in Sanya, China. <http://unepinquiry.org/g20greenfinancerepositoryeng/>

[22] Sustainable finance looks more broadly at environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors.

[23] Sustainable Finance Study Group. Synthesis Report. July 2018.