Click here to view our map showing India’s positioning in the virtual BRI.

China’s economic footprint in India seems negligible compared to its presence in other emerging markets, especially in South Asian countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Bangladesh. Whereas investments in these countries is mostly in physical infrastructure, Chinese funding to Indian tech start-ups is making an impact disproportionate to its value, given the deepening penetration of technology across sectors in India. TikTok, owned by ByteDance, is already one of the most popular apps in India, overtaking YouTube; Xiaomi handsets are bigger than Samsung smartphones; Huawei routers are widely used.

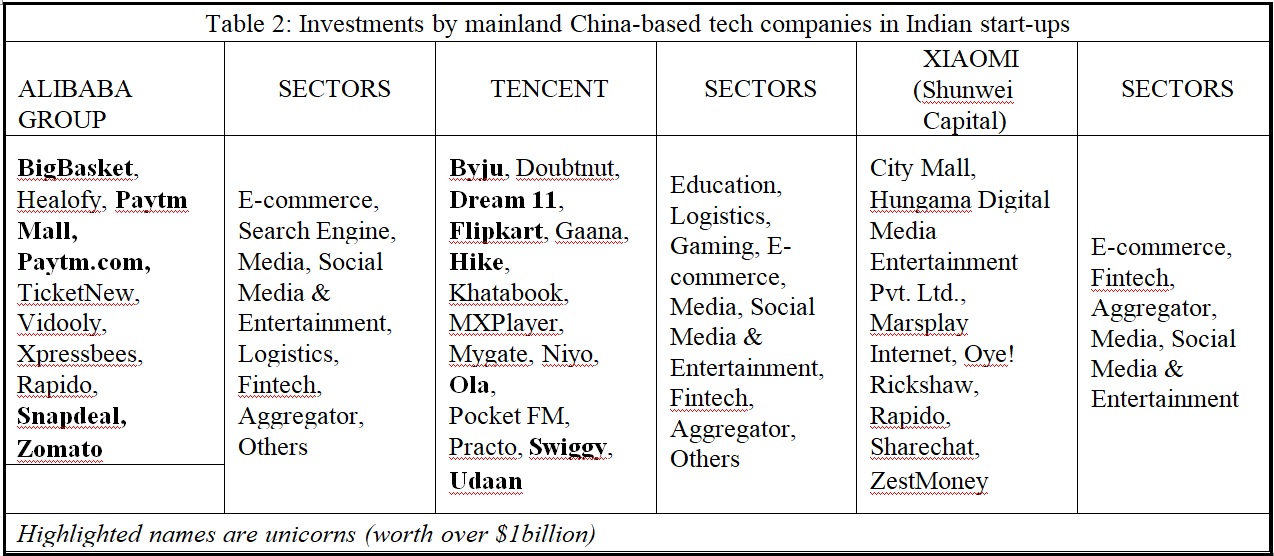

These are investments made by nearly two dozen Chinese tech companies and funds, led by giants like Alibaba, ByteDance and Tencent which have funded 92 Indian start-ups, including unicorns such as Paytm, Byju’s, Oyo and Ola. (See Table 2)

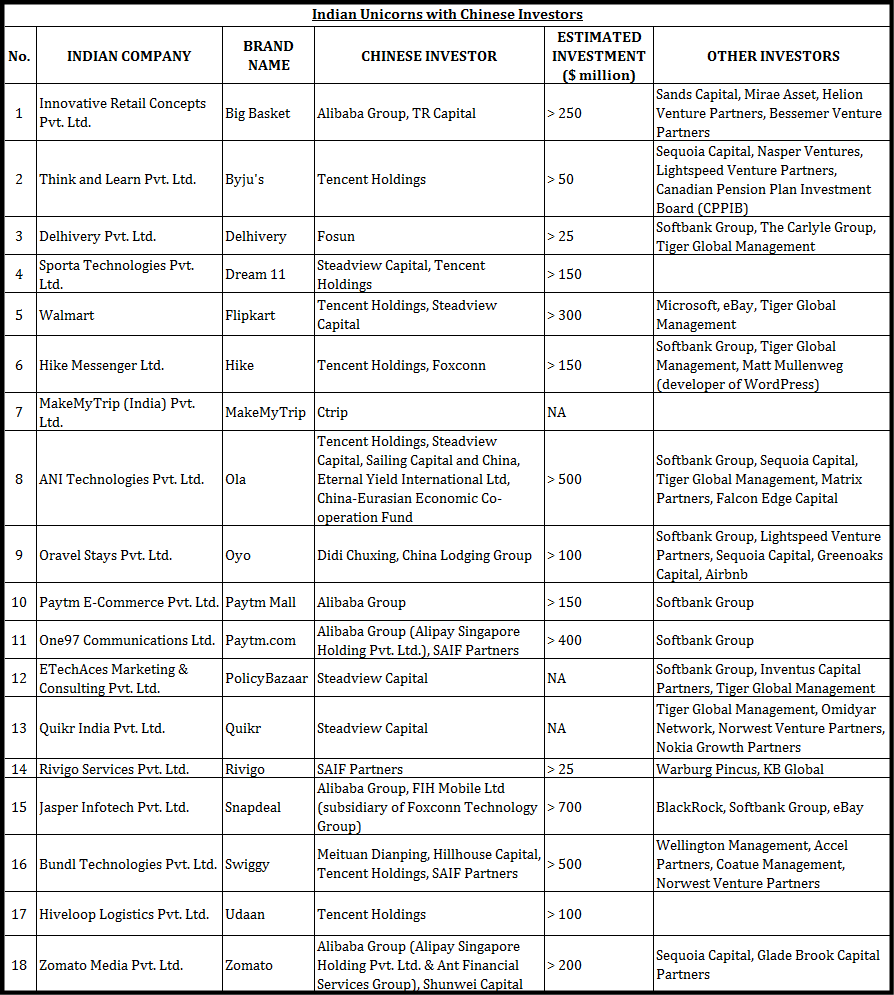

Over the course of one year, Gateway House has conducted a deep study of Chinese investments in India as part of a larger research project on Chinese investments in India’s neighbourhood. The findings are remarkable: 18 of the 30 Indian unicorns have a Chinese investor. This means that China is embedded in Indian society, the economy, and the technology ecosystem that influences it. Unlike a port or a railway line, these are invisible assets in small sizes – rarely over $100 million – and made by the private sector, which doesn’t cause immediate alarm.

All this adds up to just 1.5% of the total official Chinese (including Hong Kong) FDI into India.[1] This doesn’t cover investments made by funds based out of Singapore and elsewhere, where the ultimate owner is Chinese, so the actual investment in India will be higher.

The single largest Chinese investment in India is the $1.1 billion acquisition of Gland Pharma by Fosun in 2018. This accounts for 17.7% of all Chinese FDI into India, but it is unique. Gateway House identified just five other investments (FDI) by Chinese companies which exceed $100 million. This includes the $300-million investment by MG Motors.

China is most active in India in the start-up space. Gateway House has identified over 75 companies, with Chinese investors concentrated in e-commerce, fintech, media/social media, aggregation services and logistics. A majority – more than half – of India’s 30 Indian unicorns (start-ups with valuation of over $1 billion) have a Chinese investor. (See Table 1)

Why is China seeing such success in Indian tech? It’s because Indian start-ups rely disproportionately on overseas venture capital (VC) funding – all start-ups worth over $1 billion are foreign-funded. Some like Flipkart and Paytm have been acquired outright. India still does not have a Sequoia or Google of its own. Reliance Industries, through Jio, is trying to replicate Alibaba’s successful model in India.

Most Indian VC financiers are wealthy individuals/family offices – and cannot make the $100-million commitments needed to finance start-ups through their early losses. For instance, Paytm incurred a loss of Rs 3,690 crore in FY19[2] while Flipkart lost Rs 3,837 crore over the year.[3] That leaves Western and Chinese investors as the dominant players in the Indian start-up space. Global giants like Sequoia (U.S.), Softbank (Japan) and Naspers (South Africa) back virtually every large Indian start-up. They are also all big investors in China’s new-economy companies, have experience of that intensely competitive market and growth, and seek to repeat their success in India.

Chinese investors in Indian start-ups can be divided into two categories:

1) dedicated VC funds, such as CDH Investments, Hillhouse Capital, SAIF Partners and Ward Ferry, mostly based in Hong Kong. They are akin to professional global investors, such as Sequoia or Softbank, and look for financial returns;

2) tech companies, such as Alibaba, Tencent and Xiaomi (or their various arms), which want a serious presence in the Indian market, just as Walmart (via Flipkart) and Amazon do.

These investments bring up three concerns for India: data security, propaganda and platform control.

Data security

Chinese companies such as Alibaba and Tencent have their own ecosystems, which include online stores, payment gateways, messaging services, etc. An investment by a Chinese firm can pull the Indian company into this ecosystem, which may mean loss of control over data.

Typically, in investments by a consortium of venture capitalists, one of the partners takes the lead in advising the start-up. If Alibaba/Tencent is playing this role, it can encourage the start-up to use pre-existing Chinese solutions for its tech requirements – again leading to loss of control over data.

If this process is followed across a range of companies – a taxi service, a hotel aggregator, online retail outlets, a payment provider – it permits an intrusive, comprehensive profile of an individual and his/her habits. Grindr is an example. (See box)

| Grindr: a security risk? Grindr, a hook-up app for the LGBT community, is an example of how data can be misused. Grindr was acquired in 2016 by Chinese gaming company, Kunlun. During the Cold War, homosexual blackmail was used by Stasi and the KGB to target vulnerable officials in the West. There is still considerable stigma attached to homosexuality in India – can a government official be blackmailed with such information? The U.S. government has flagged off ownership of Grindr as a national security risk, and ordered the Chinese owner to divest a majority stake by 2020.[4] |

Western companies have similar access to private data too – but there is national and global oversight and more transparency in their systems.

Propaganda/influence/censorship

The Chinese government keeps a tight control over its media at home. Most of the Western social media apps (Facebook, Twitter) and many of the leading news outlets are banned in China. Large multinational corporations are unwilling to lose the Chinese market and wary of offending the Chinese government. This has given China a veto over free speech in many Western countries, seen recently in the high-profile case of the National Basketball Association (U.S.)[5] speaking out about the protests in Hong Kong.

Investments in Indian social and other media (including those in regional languages) as well as start-ups could lead to a subtle push toward the Chinese narrative on bilateral issues and disputes with India, a shift to a more favourable depiction of China and suppression of criticism. For instance, TikTok censors topics that are sensitive to the Chinese government.[6] This kind of influencing by a foreign totalitarian government is detrimental to an open and free society.

Platform control

The Internet is split into two major camps: the ‘traditional’ open internet dominated by Western companies, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google (FANGS) and the ‘closed’ Chinese internet – almost an intranet – which restricts outsiders and is closely monitored and controlled by the state. Companies like Alibaba and Tencent are enablers and beneficiaries of this system. By restricting access to foreign players, China was able to create its own champions – which now rival the West’s.

If Alibaba, Tencent and other Chinese tech majors replicate their internet ecosystems in India, this can create a systemic risk. An ecosystem such as this controls access to end-users; it means other companies (retailers, financing firms and media) will have to follow the standards/technologies prescribed to them. Alibaba/Tencent will be in a position like Google – they can decide which firm will succeed or fail by controlling user access, using their own technologies. Imagine: the Indian economy could use Chinese tech for critical applications.

India has not participated in China’s Belt and Road Initiative and has yet to take a final decision on allowing Huawei into India’s 5G telecom. But through these investments in start-ups, India may find its economy tied ever closer to China’s.

Click here to view our map showing India’s positioning in the virtual BRI.

Amit Bhandari is Fellow, Energy and Environment Studies Programme, Gateway House.

Aashna Agarwal is Researcher, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, “Quaterly Fact Sheet, Fact Sheet on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) From April, 2000 to June, 2019″, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2019,

https://dipp.gov.in/sites/default/files/FDI_Factsheet_4September2019.pdf

[2] Bhakta, Pratik, “At Rs 3,960 crore, losses mount 165% for Paytm parent One97″, Economic Times, 10 September 2019,

[3] PTI, “Flipkart logs loss of Rs 3,837 crore in 2018-19″, Economic Times, 28 October 2019,

[4] Wang, Echo, “China’s Kunlun Tech agrees to U.S. demand to sell Grindr Gay dating app”, Reuters, 14 may 2019,

[5] CBS News, “China’s CCTV threatens to pull NBA broadcast ties as commissioner defends free speech”, CBS News, 8 October 2019,

[6] Hern, Alex, “Revealed: How TikTok censors videos that do not please Beijing”, The Guardian, 25 September 2019,