Nothing prepared me for a recent visit I made to the Global Vipassanā Pagoda near Gorai village, in the northern reaches of Greater Mumbai. First, there is the sheer size of this glittering, golden Burmese dome, standing in splendid isolation on a verdant peninsula between Gorai village and the Arabian Sea. It is an exact replica of Myanmar’s 11th century Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon (erstwhile British Rangoon), but unlike the Shwedagon this one, made of stone, is hollow at the centre to house one of the largest pillar-less halls in the world, with a seating capacity of 8,000. [1]

Second, to the casual visitor and Vipassanā student-there is a learning centre in the pagoda complex- the symbolism of this Shwedagon replica does not elicit curiosity other than it being possibly the only Burmese-style pagoda in the city. It’s a piece of Myanmar in Mumbai. And possibly, that Vipassanā meditation retained its pristine form only in Theravada Buddhist Burma for centuries before returning to India in the 1960s.

However, the importance of this Pagoda does not lie in this narrative of return to its native homeland (the land of Gautama Buddha) but in the many stories that led to its construction in Mumbai, stories that reference a history that maps the geopolitical and economic connections between Mumbai and Myanmar.

A trading arc – Rangoon to Bombay

The connections between British Bombay and Burma began soon after the Second Anglo-Burmese War of 1852, which not only consolidated the territory that the British gained on the Arakan coast during the first war of 1824-26, but also led to the British occupation of what came to be known as Lower Burma and its strategic ports, situated in the valley and on the delta of the Irrawaddy river.

Though Calcutta, the capital of British India, was the natural nodal port for the Burmese rice trade due to its proximity to the Burmese ports of Sittwe, Pegu (Bago), and Bassein (Pathein), Bombay’s stake in the lucrative Burmese commodities trade began with its demand for Burma teak.

This came from the city’s ship-building yards and exporters to West Asia, Britain and Europe. It was also needed in the 1850s for the building of the Indian railways. By April 1853, the first railway line on the subcontinent was inaugurated between Bombay and Thana (today’s Thane), and the newly incorporated London-headquartered Great Indian Peninsula Railway (today’s Central Railway) had plans to lay tracks connecting the city to its cotton hinterland. [2]

This lucrative trade with Burma gave rise to numerous Bombay-based agencies entering the business in rice, pulses and teak wood. Alongside the merchants who travelled to British Burma, there was an influx of settlers, ranging from small traders and shopkeepers to labourers and civil servants, who later manned the administration, the ports, and police force of British Burma. The Indian presence extended to Mandalay, when Upper Burma was annexed by the British after the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885-86.

Some of the Indian communities that had a sizeable presence in British Burma, which, at first, was annexed to British India, and later, administratively separated in 1937, were the Bengalis (both Hindu and Muslim); Chettiars (who became rice traders, land-owners, and money-lenders); Tamilian, Telugu, and Malayali workers; Hindi-speaking labourers from the British United Provinces; and Sikhs, Marwaris, and Parsis from the subcontinent’s west coast.

The history of the Marwari diaspora represents how the linkage between Bombay and Burma was established through community-based trading networks. The Marwaris are central to the spread of the diaspora from Bombay to Rangoon. This community settled in Burma as a natural expansion of its trading network, which extended from the east to the west coast of the subcontinent, with Calcutta as headquarters.

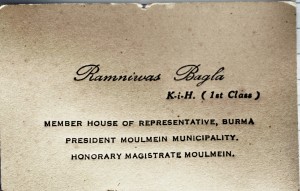

It was the descendant of one such family, the Baglas of Moulmein (Mawlamyine) and Rangoon (Yangon), who was my guide to the pagoda complex. The Baglas trace their roots to Churu village in Rajasthan and have family settled along a part-sea, part-land route that stretches from Rangoon to Moulmein, then onto Kolkata, Varanasi, Churu, and Mumbai. That this family has deep roots in Myanmar is evident from the fact that its patriarch, Ramnivas Bagla, was a former member of Burma’s parliament.

This network of businesses and homes, as is the case for traders who stayed behind, still exists, however tenuously, today.

Like most community-based merchant networks from the subcontinent, what circulated through these trade-routes were not just commodities. They sent along suitable brides, children travelled for higher education to Calcutta and Bombay, staff from the community pool and domestics were regular sojourners. The pioneers, who explored and set up businesses in new regions, like erstwhile Burma, were the alpha male members from these joint families.

Mumbai-Myanmar today

This brings us back to the Global Vipassanā Pagoda — and its significance for this 150-year linkage between the city and Myanmar.

Apart from the overt message of the Pagoda itself, which denotes the return of non-sectarian Buddhist Vipassanā meditation to the Indian subcontinent from Myanmar, it also reaffirms the existence of strong economic, social, and cultural bonds between the two countries.

These confluences come through the story of Satyanarayan Goenka, the founder of the Global Vipassanā Pagoda, a Burmese Indian of Marwari descent and a Vipassanā teacher who trained under Sayagyi U Ba Khin, an ethnic Burmese and civil servant. Goenka, whose family history follows the trajectory of the Bagla family, returned to Bombay in 1969. [3]

Most Burmese of Indian descent, who fled Burma (Myanmar) at various inflexion points in that country’s history-whether it was the Japanese invasion in 1942 during World War II or the military junta’s takeover in 1962 or thereafter- returned to India as uprooted Burmese. Even today, many nurture the hope of revisiting their childhood now that Myanmar has emerged from five decades of military rule.

Many Burmese Indians like Goenka and my guide to the Gorai Vipassanā centre assimilated the practise of non-sectarian Buddhism into their daily lives alongside their observance of Hinduism, a legacy from Myanmar where many Hindu temples also host an idol of the Buddha.

Other convergences too exist: many are fluent in spoken Burmese and its script as also the preparation of Indian dishes, like the tri-coloured (tirangi) rice in which they use black, red and white Burmese rice.

Today, people of Indian origin (PIO) in Myanmar form about 4% of its total population. In 2004, their number was estimated to be 2.9 million , of which 2,500,000 were PIO, 2000 Indian citizens, and as many as 400,000 deemed stateless. Only a fraction of the PIO are Myanmar citizens, many remained un-enumerated as citizens after Burma’s independence in 1948. [4]

With strengthening bilateral ties between the two countries and the recent formation of a civilian government in March 2016 by Aung Sung Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, the legal status of the historically significant Indian diaspora should be addressed. It is this community of Indians that has provided the soft fluencies of economic, social and cultural commons between the two countries.

Sifra Lentin is the Mumbai History Fellow at Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2016 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] Global Vipassana Pagoda, Concept and Planning, <http://www.globalpagoda.org/concept-and-planning> (Accessed on 7 October 2016)

[2] Aklekar, Rajendra B., Halt Station India (Mumbai, Rupa, 2014), p. 22.

[3] Global Vipassana Pagoda, S N Goenka, <http://www.globalpagoda.org/s-n-goenka> (Accessed on 7 October 2016)

[4] Chaturvedi, Medha, ‘Indian Migrants in Myanmar: Emerging Trends and Challenges’, Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs, 2015 https://www.mea.gov.in/images/pdf/Indian-Migrants-Myanmar.pdf (Accessed on 9 October 2016)