This is the third and final part of this series. Read the first part here and the second part here.

Japan is currently celebrating the dawn of a new era, named ‘Reiwa’ (‘beautiful harmony’), and the coronation of its Emperor Naruhito. This is cause for celebration for the multi-generation mercantile Indian Japanese community too, which has seen the reign of four emperors.[1] In 1923 (before the Great Kanto Earthquake the same year) there were 170 Indians in Yokohama and 175 in Kobe.[2] Today there are approximately 34,348 Indians in Japan.[3] Most of these families are permanent residents of Japan,[4] while those who returned to India or migrated elsewhere have fond memories of their families’ pioneering days.

Indian merchants had a crucial role to play in expanding Japan’s trade with the rest of the world, particularly within Asia.[5] These trading firms, owned by Parsi, Sindhi,[6] Bohri, Marwari and Jain merchants, mostly originated from the Presidency of Bombay,[7] using its two most important port cities – Bombay and Karachi – as an entry and exit point for their overseas travels and trade and circulation of employees, and even brides, from the community pool. Remittance and credit facilities offered by banks fostered the India-Japan trade.[8]

While the British and European companies and big multinational firms traded in large quantities of raw cotton, yarn and indigo with Japan, the Indians leveraged their community networks to market Japanese silks, textiles, pearls, lacquerware, pottery and curios in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Saigon, Manila, Penang, Rangoon, Trincomalee, Calcutta, Bombay, and sometimes globally, (especially in the case of Sindhi merchants) to the Arabian Peninsula, Africa, Egypt, Gibraltar, Spain and the Americas. This made them indispensable to city governments, like Yokohama and Kobe, where they were largely clustered, and their prefectures (Kanagawa and Hyogo).

This monument in Yokohama, called the ‘Indian Fountain’, is in memory of the Indians who died in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1 September 1923

A tug of war erupted between various trade associations of the Yokohama and Kobe silk industries and between the two city governments when it came to wooing the Indian community back after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1 September 1923 destroyed the Indian neighbourhood of Yamachita-cho[9] (in Yokohama). It killed 23, including nine children; those remaining fled to Kobe-Osaka. Yokohama succeeded in having the Indians return: 14[10] out of the 60 firms, which were earlier based there, returned in 1924, but only after the government constructed 16 two-storied wooden houses for them.[11] This showed how important the Indian community was to the Japanese government.

The earliest Indian firms

Yokohama city, the site of the first Indian settlement as early as the 1870s, was a hub for the Japanese silk trade because of its port. According to a booklet, “Commemorating 60 years of India-Japan Relations”,[12] the first settlers were a Parsi, named Kumazawa Impuresu (who became a naturalised Japanese), and a Bohri, called Essabhoy (of the firm A.M. Essabhoy). They, with fellow traders, exported Japanese silk fabrics (which were cheaper than the Chinese variants) and imported indigo, foreign rice and the raw materials for dyeing. Matchboxes, stamped with the name of A.M. Essabhoy, indicate that this firm was most likely also involved in the local retail trade.

A namesake, but no blood relation to A.M. Essabhoy, was M. Essabhoy & Sons, a firm also established in Yokohama, though in the early 20th century, through a partnership between Mullah[13] Essabhoy and a second cousin, who were said to be importing spices and jute (from Calcutta) into Japan and Southeast Asia. “They were based in Japan, but also had branches in Hong Kong and Singapore,” says Esmail Essabhoy, a spokesperson for the family.

In 1882, the first Sindhi firm – Wassiamull Assomull & Co. – opened an office in Yokohama. Other firms, K.A.J. Chotirmall & Co. Ltd., Pohoomull Bros., T. Motoomull and others, soon followed.[14] The J. Kimatrai group, founded by Jhamatmal Kimatrai, was headquartered in Yokohama, unlike the many which had branches there. A scion of the family says her father made his fortune in Japan during the First World War (1914-18), “buying Japanese fabric cheap and selling it through branches (set up with local partners) in Rangoon (Burma), Saigon (Vietnam), Manila (Philippines) and across the Far East (Singapore and Hong Kong)”. The demand for affordable Japanese textiles arose as supplies from British mills stopped during the war.

Business practices

Making money was only one aspect of Indian businessmen’s success story in Japan. Their dependence on local employees was always greater in Japan than in other South or South East Asian branches as the Indian community always stayed small because of Japan’s strict visa regulations. The pre-War maximum in 1937 was 1,000 Indians.

Apart from giving local people jobs, this worked well for the Indian employers too because, “The Japanese are loyal, trustworthy and always punctual – like the trains in Japan,” says a member of the Kimatrai family, describing their efficiency.

The Indian merchants also relied on the urikomishō, or local selling agents of silk yarn, habutae,[15] silk satin and silk crepe, who served as the bridge to the silk manufacturing hinterlands of both Yokohama and Kobe.

The focus now shifted from silk to cotton. The growth of the Japanese textile industry begins with the establishment of the Osaka Spinning Mill (1888), which not only produced superior yarn, but drastically reduced the industry’s dependence on foreign imports. The direct shipping route, between Kobe and Bombay, which was set up by Tata Lines and Nippon Yusen Kaisha (the Japan Mail Steamship Co. Ltd.), in 1893,[16] led to a great trade in cotton yarn and raw cotton from Bombay for the Japanese mills in Kobe and its surroundings. This trade was driven by big firms from Bombay,[17] and later by Japanese companies, like Mitsui Busan,[18] but the actual distribution and sale of Japanese mill-made textiles was largely the purview of Indian merchants in Japan and their Asian and global network.

Japanese cultural influence

Japan had a profound influence on the Indian diaspora. Many spoke the language fluently and imbibed their cultural ways. Esmail Essabhoy recalls how, “When the entire Essabhoy family (his father’s side and his cousin’s) returned to India soon after the First World War, they brought with them two Japanese nannies for each of their youngest daughters. The nannies were addressed by everyone as Ama San. I remember that as children we used to address our father as Papa San.”

As there were no English schools in Japan then, many Indian children went to Japanese schools – a disadvantage when families were forced to flee to British India and other British colonies after Japan entered the Second World War in 1941. On the other hand, their personal knowledge of Japan enabled many of these families to set up companies with Japanese collaboration and know-how in India before the war. The existence of these companies is unknown in Indian economic history because locally well-known business groups were not involved in setting them up, but they were notable in their time.

In fact, the first large-scale matchstick factory to be set up in Calcutta was Esavi by the Essabhoy group, in the early 1920s. This factory employed 1,000 workers and had Japanese technicians on site. The company flew in women workers from Japan to train their Indian counterparts in packing matchsticks neatly into their boxes.[19] The J. Kimatrai Group ran a well-known silk mill, N. S. Mills, which was founded in 1939 in Ahmedabad and was in operation until 2009. It was popular for its silk satins, silk brocades, and once well-known for the sharkskin fabric it manufactured for men’s suits, all with Japanese know-how.

The 1950s and after

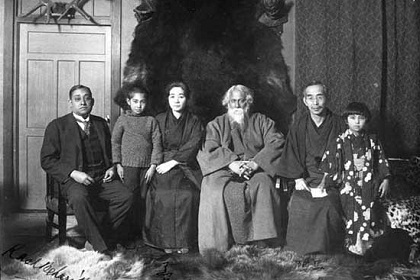

From left to right, Rash Behari Bose, Rabindranath Tagore (centre) and the Soma family at Nakamuraya, supporters of the Indian cause who hid Bose for many months

The Second World War disrupted, but did not sever, ties that the old Indian firms had with Japan. Most left, but some (about 141 out of 1,000) stayed behind during the war. A few Indians were imprisoned in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, but released when Japan forged an alliance with Indian nationalists, Ras Behari Bose and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, against the Allies.

Even before formal diplomatic ties were established by a now independent India and a post-War Japan in 1952, Indian merchants began returning to Japan and were welcomed by local city officials. Those affected by the Partition of India in 1947, such as the Sindhis and Sikhs, found Japan an attractive alternative in its reconstruction phase, even when compared to independent India.

Many had to cope with a changed trade milieu now. Some, like Sundeep Shah’s family, was able to retain its pearl business, but others had to switch to electronics, cars and real estate, as Japan itself changed its economic model to a capital-intensive one in iron and steel, chemicals, electronics and automobiles. Many embraced these changes gamely, but were also hit financially when Japan’s decades-long post-war prosperity faced an economic meltdown in the 1990s.

Today, the Indian community in Japan is wrongly identified with the recent influx of Indian software engineers with their young families, who live in the Edogawa neighbourhood of Tokyo and are posted usually on three-year contracts. They bear no comparison to their business forebears: Indian family-run firms in Kobe, Osaka and Yokohama go back 150 years and are a mark of the resilience of India-Japan ties.

Sifra Lentin is Adjunct Fellow, Bombay History Studies, Gateway House.

This is the third and final part of this series. Read the first part here, and the second part here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

Reference

[1]Namely the Meiji Emperor (1867-1912), the Taishō Emperor (1912-1926), the Shōwa Emperor (1926-1989), and Emperor Akihito (1989-2019) who abdicated the throne due to health reasons in favour of his eldest son.

[2] Shimizu, Hiroshi, The Indian merchants of Kobe and Japan’s trade expansion into Southeast Asia before the Asian-Pacific War ( Japan Forum, Volume 17, Issue 1, 2005), p. 28.

[3] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Bilateral Brief India Japan December 2018, <https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Bilateral_brief_India-Japan_december_2018.pdf >

[4]In Kobe, which has the largest concentration of old Indian families, most are ‘permanent residents’ in spite of being born and brought up in Japan; only a few are Japanese citizens. They enjoy all the benefits of citizenship except the right to vote. Recently, on 23 April, 41-year-old Puranik Yogendra became the first Indian-origin Japanese citizen to win an election in Japan.

[5] It was after Japan signed treaties of amity and friendship with the western powers, beginning with the Harris Treaty (1858) with the United States, that Japanese ports and markets were opened to trade.

[6]All through this article the reference is to Hindu Sindhi merchants and not Muslim Sindhis, who in this period (1870s to 1947) were largely peasants and small farmers in Sindh.

[7] The Presidency of Bombay was an administrative unit of British India, whose capital city was Bombay. Commonly referred to as Bombay Presidency it included at its height what was formerly the Maratha Empire (from 1815), Sindh (from 1843 to 1936) which includes the cities of Karachi and Hyderabad (Sindh), Aden, the present-day Indian state of Gujarat, parts of the present-day Indian state of Karnataka, and for a short period a part of the Malabar Coast. It also had numerous Princely Kingdoms within its purview.

[8]Notable banks with branches in Bombay and also one in Yokohama and Kobe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were the Bank of Western India (which later became the Oriental Banking Corporation), Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China, HSBC, and the Yokohama Specie Bank.

[9]Indian merchants once operated from and lived in ‘shop-houses’ in the historic district of Yamachita-cho, which lies within Yokohama city’s port and harbour or Minato-Mirae area.

[10]These firms included Pohoomull Bros., P. Mullchand, J. Kimatrai, Kishinchand Chellaram & Sons, Dhanamal Chelaram and Verkomal Shewakram who returned on the Nippon Yusen Kaisha ship Hachiman Maru on 24 October 1924 and were welcomed back with great fanfare.

[11]Shimizu, Hiroshi, The Indian merchants of Kobe and Japan’s trade expansion into Southeast Asia before the Asian-Pacific War (Japan Forum, Volume 17, Issue 1, 2005) p. 31.

[12]This booklet is jointly produced by Yokohama Archives of History and Yokohama Museum of Eurasian Cultures. It commemorates 60 years of the bilateral relationship from 1952, when independent India and Japan established diplomatic relations after the Second World War (1939-45), hence the anniversary falls in 2013.

[13]The title “Mullah” was given to Essabhoy (it is his first name) by the spiritual head of the Bohri community — the Syedna. This Syedna is the grandfather of the present Syedna. Interestingly, Essabhoy’s partner and second cousin was also named Essabhoy.

[14]Chandru, G.A. (1993), The history of Indians in Japan, in J.K. Motwani, M. Gosine, and J. Barot-Motwani (Edited), Global Indian Diaspora: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow (New York, Global Organization of People of Indian Origin, 1993), p 322-23.

According to G.A. Chandru, around 1872, W. Assomull, D. Nanoomal, Pohoomull Bros. and a Parsi firm J.B. Bhesania (connected with the Tatas) began trading from Yokohama. They were followed by J.T. Chainrai in 1887 and Chotirmal in 1893.

[15]A soft lightweight Japanese silk in plain weave, which is also referred to as Habutai.

[16]Refer to Part 1 of this series ‘Imperial Japan’s trade with Bombay’ https://www.gatewayhouse.in/bombay-japan-trade/

[17]The two biggest were R.D. Tata & Co. Ltd. and E.D. Sassoon & Co.

[18] Mitsui Busan translates to Mitsui Trading Company.

[19]The Essabhoy Group also opened two other companies with Japanese collaboration, one a rubber products factory (Indian Rubber Goods Manufacturing Co.) and a silk manufacturing factory. All three were located in Calcutta.