This article is based on the author’s visit to Leh district of Ladakh in April 2018.

Click here to view our repository on the Arc of India’s Border Security.

On June 19, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), the ruling coalition in Jammu & Kashmir state, ended their three-year partnership. The state is now under governor’s rule until alternative arrangements can be made or fresh assembly elections are called. The BJP’s General Secretary, Ram Madhav, said that “resentment in Jammu and Ladakh regions has been growing over lack of proper development and progress and also a perceptible sense of discrimination.”[1][1]

The BJP’s assertions come none too soon. Ladakh, the third part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, has been largely unnoticed amid the continuing political ado in Kashmir – unnoticed, that is, except by China, which is quietly extending its influence in the politically impotent but strategically vital region. It is a simmering but potentially more serious long-term problem in Ladakh.

Muslim-dominated Kashmir Valley in the north, which occupies 15% of the state’s land mass gets maximum attention from India, Pakistan and the international community. Hindu-dominated Jammu, 25% of the state’s territory, has seen increasing focus from the BJP at the centre. But Buddhist-dominated Ladakh, which comprises almost 60% of the state but accounts for just 2% of the population[2][3], is all but invisible in policy circles. Its name isn’t even included in the state’s official name. This is ironic since Ladakh has historically protected India from the Tibetan and Mongol invasions from the north. It is now sandwiched between Pakistan-occupied Gilgit Baltistan and China-occupied Aksai Chin and is strategically important – and perhaps as a result, is the subject of a running border dispute.[4]

While it has received some border infrastructure development from India, Ladakh may be ignored in part because it is largely peaceful. That will no longer be an excuse. For neighbouring China has slowly been increasing its influence, focusing not just on the border, but exploiting sectarian differences among the monasteries of Ladakh. The region is the site of frequent border face-offs with China – starting with the Sino-Indian War of 1962 and continuing with frequent territorial incursions as was seen most prominently during the Depsang Valley standoff with China in 2013.[5] Of late it has been misusing Himalayan Buddhism[6], a tactic China has used extensively and for decades in Tibet. [7]

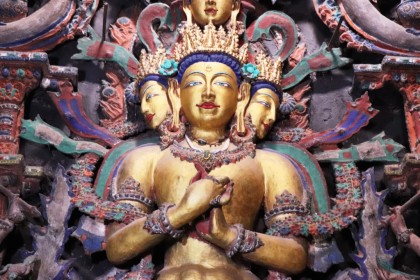

This is the most insidious threat to Ladakh and to India. For 20 years, China has been quietly paying for the restoration of art and artifacts in Ladakh’s many neglected border monasteries. Its beneficence has been focused especially on approximately 260 Drukpa-sect monasteries, which own significant and valuable relics of Ladakhi Buddhist art, revered by the locals. Ladakhis are largely from the Drukpa sect, which has a distinct Indian heritage and was founded by the Indian scholar Saint Naropa in the 11th century.[8] Many Drukpa monasteries, like ones in Hemis village, are strategically located on the India-China border, where China is fortifying its infrastructure and security presence.

According to the Drukpas, Chinese government-endorsed monks from the Tibet-origin Karma Kagyu sect (one of the Tibetan Buddhism’s wealthiest sects), have been coming to Ladakh with cash and restoration skills, which have been gratefully accepted. Under cover of restoration, these ancient and priceless iconographies, paintings and sculptures have been modified, whitewashed, or removed and sold in the international black market and to keen Chinese buyers. Sometimes the Drukpa monasteries are given cash in the form of high-interest loans to restore their art. When unable to repay, they have been compelled to hand over their monasteries.

In other words, by indebting them Hambantota-style[9], this strategy has desecrated the precious heritage of the Ladakhis, and pitted one Himalayan Buddhist sect against the other.

There are conflicting reports of this skillful exploitation of the traditional intra-sect competition between the Drukpas and the Karma Kagyus to control monastery land and art on the ground. For instance, according to Jigme Pema Wangchen, Gyalwang Drukpa – the head of the Drukpa Lineage, in 2014, the Karma Kagyu took over Drukpa monasteries in the Mount Kailash region of China, a play in which the Chinese government was involved.[10] However, the Karma Kagyu say that the monasteries were already crumbling and desecrated and they simply restored them.

That occupation has drawn India’s attention to the Chinese strategy for Buddhist Ladakh, and to India’s laggard response, neglect and confused approach to the region. Ordinary Indians, and sometimes government officials too, misrepresent Ladakh as ‘little Tibet’ – a moniker that hurts Ladakhis, who take pride in being Indian. Young locals in Leh often recount to visitors the past blunders of the Ministry of Tourism’s Incredible India campaign, which they allege used Tibetan instead of Ladakhi iconography (The Ministry couldn’t be reached for comment). Although the Dalai Lama is revered by the Ladakhis, Drukpa practices are very different from his Tibetan Gelugpa Buddhist sect.

In addition, Ladakhis who travel frequently to other parts of India for jobs and education purposes, are frequently stereotyped as Nepalese, North-easterners or even Chinese.[11] Ladakh’s remote location, its unique cultural profile and an overwhelming focus on the Kashmir Valley reinforces such ignorance. These factors have contributed to the marginalisation of Ladakhis in the national discourse even though they continue to play a significant role in India’s border security.[12]

Righting this wrong is urgent. India needs to support the Drukpa monasteries and their restoration. Already Ladakh is a tourist hub, and this can add to the attraction. All-weather road links through the Zojila tunnel and the proposed Srinagar-Kargil-Leh railway line need to be expedited. Ladakh also lacks uninterrupted supply of electricity and reliable mobile phone networks, with only two telecom companies providing connectivity in and around Leh town. India has kept pace with China’s infrastructure buildup on the Line of Actual Control by connecting remote border villages with main towns and activating high-altitude airfields like the one at Daulat Beg Oldie. Finally, the state must conduct long-postponed local body elections so Ladakh can get its due of central government funds for block-level developmental activities. These elections have not been held for the past two years because of the deteriorating security in the Kashmir Valley[13] – a fact that causes much resentment in both Ladakh and Jammu.

India must rebuff China’s push, which could change the demographic character of Ladakh. Young Ladakhis have seen the Chinese Han spread into Tibet, and carry deep anxiety about the potential loss of their culture and identity. By nurturing the goodwill, culture and administration of this strategic border region, India can project a positive story in Kashmir one far away from the violence and pessimism that currently dominates the discourse.

Sameer Patil is Director, Center for International Security and Fellow, National Security Studies, Gateway House.

This article is based on the author’s visit to Leh district of Ladakh in April 2018.

Click here to view our repository on the Arc of India’s Border Security.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] ‘Press statement issued By BJP National General Secretary, Shri Ram Madhav On 19 June 2018′, 19 June 2018, <http://www.bjp.org/en/media-resources/press-releases/press-statement-issued-by-bjp-national-general-secretary-shri-ram-madhav-on-19-june-2018>

[2] LAHDC Leh, ‘Leh At Glance’, <http://leh.gov.in/pages/glance.html>

[3] District Administration, Kargil-Ladakh, ‘About population and density of the district’, <http://kargil.gov.in/profile/profile.html>

[4] Jinpa, Nawang, ‘Why Did Tibet and Ladakh Clash in the 17th Century? Rethinking the Background to the ‘Mongol War’ in Ngari (1679-1684)’, Tibet Journal, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2015, pp. 113-150

[5] Patil, Sameer, ‘The new, sharper sabre from Beijing’, 26 April 2013, Gateway House, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/the-new-sharper-sabre-from-beijing/>

[6] Buddhism practised in India- Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh region, along with regions in Nepal, Bhutan and China’s Tibet is collectively referred as ‘Himalayan Buddhism’. Its four major sects are: Kagyu (major sub-sects being Karma, Drukpa lineage and Drikung Kagyu), Nyingma, Sakya and the Gelugpa.

[7] Dotézac, Arnaud, ‘Buddhist soft power, Chinese-style’, Market, 23 June 2014, <http://www.market.ch/fr/blog/details/article/geopolitique-buddhist-soft-power-chinesestyle.html>, accessed on 16 April, 2018

[8] Gyalwang Drukpa, ‘Naropa’, <http://www.drukpa.org/en/drukpa-order/59-drukpa-lineage/lineage-forefathers/280-naropa>

[9] Bhandari, Amit and Chandni Jindal, ‘Sri Lanka: Debt-trapped’, Gateway House, 31 January 2018, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/chinese-investments-in-sri-lanka/>

[10] ‘On Forced Conversion of Drukpa Monasteries’, 10 September 2014, <http://www.drukpa.org/en/news-updates/news-in-2014/359-on-forced-conversion-of-drukpa-monasteries>

[11] Vasan, Sudha, ‘Being Ladakhi, Being Indian: Identity Formation, Culture and Community’, Economic and Political Weekly, April 8, 2017, Vol. LII, No. 14, p. 43

[12] To assuage its administrative grievances, the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) was set up in 1995. But this has proved to be an inadequate instrument with lack of robust financial support from the state government for developmental activities. The locals continue to demand more autonomy than what has been envisaged by the LAHDC. For more than a decade, a group of Ladakhis, through Ladakh Union Territory Front, have projected a Union Territory (UT) status with an elected Legislature and Lt. Governor for Ladakh, as the best solution. This demand though popular, hasn’t cut much ice particularly since it is directly linked to the Article 370 (which gives an autonomous status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir) of the Constitution. Yet, the demand persists.

[13] Ali, Muddasir, ‘Panchayat polls likely after Yatra’, Greater Kashmir, 8 April 2018, <http://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/front-page/panchayat-polls-likely-after-yatra/281338.html>