This article is the first in a two-part series. Read part two here.

This year marks a century[1] of the diamond trade between Antwerp and Bombay. Proof of this century-old overseas trade is a sepia-toned photograph from 1928 of the last Nawab[2] of Palanpur, Taley Mohammad Khan, with his compatriot Palanpuri Jain merchants standing in front of the Diamantclub Van Antwerpen (Diamond Club, Antwerp). (See photo 1) Even more evocative is another photo of the same royal visit but this time including the wives of some of the Jain Antwerp merchants dressed in traditional saris. They are seated in the first row alongside the Nawab of Palanpur, with their husbands and the royal entourage standing behind them. The smiling lady in the center of the photograph, Manglaben Laherchandbhai Parikh, has two young boys seated at her feet, revealing that these orthodox Jains settled with their families in the port of Antwerp as early as the 1920s, a time when wives and children typically stayed home in India. (See photo 2)

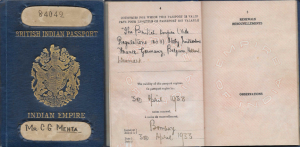

These rarely seen photographs are part of a collection belonging to Suresh Mehta, an Antwerp-based diamantaire since 1960 and whose father Chandubhai Gambhirmal Mehta was a diamond trader in Antwerp during the inter-war years of 1925 to 1933. This, says Mehta, was the first overseas tour of Nawab Taley Mohammad Khan. During that visit to Europe, the Nawab visited his subjects in Antwerp, all of whom were active participants in the city’s bustling diamond trade with India.[3] Palanpuri Jains were also involved in the London and Amsterdam diamond trades, and a few were settled in these cities. It was commonplace for the community to circulate between the three port cities in pursuit of the best deals. When the Nawab returned from his first overseas travels, he was welcomed at Bombay port and later in Palanpur with all the pomp and pageantry befitting the completion of a successful royal tour.[4]

It reflected the relationship of trust between Palanpur’s Nawabs and their Jain subjects. Palanpuri Jains were trusted administrators, treasury officials, and ministers for centuries in the Kingdom. The community’s ethics stood it in good stead when they ventured to the British colonial cities of Bombay, Madras and Calcutta, and later Antwerp, to seek their fortune as diamantaires. This is a business in which one’s word is sacrosanct, where a deal is sealed with a handshake, and credit is unheard of.

How did the Palanpuri Jains find their way to far-away Antwerp? A 1909 meeting of the community elders in Palanpur decided their young men must seek business opportunities in British colonial cities as they offered better prospects to make money than did Palanpur. Their optimism was underwritten by the success stories of Amulakh Khubchand Parikh and Surajmal Lallubhai Mehta, who entered the diamond trade in Bombay. Antwerp in Belgium then was a natural next step from where to source a steady supply of gem-quality diamonds and roughs that could be manufactured in Bombay. They made their way to Antwerp after the First World War, at a time when many Jewish diamantaires and manufacturers from Amsterdam shifted to this port city on the River Scheldt. The Jewish traders found the latter more conducive to trade and for their families.

Most diamond merchants with an Antwerp connection believe the trade between Bombay and Antwerp began in the 1950s and 1960s after the Second World War, but it was much earlier. Palanpuri Jain diamantaires from Bombay had already settled in Antwerp in the 1920s.[5]

Mehta says his father, Chandubhai Gambhirmal Mehta, whose firm was C.G. Mehta & Co., “made his first trip to Antwerp in 1925.” Although married by then, Chandubhai lived as a paying guest with a Jewish family and would return home to Palanpur every one and a half years. He had some company: there were some Jain families in Antwerp then, like Hemchandbhai Mohanlal Jhaveri of Hemchand Bros. and S.B. Shah, both from Patan and Surajmal Lalubhai, from Palanpur.

These pioneering Gujarati-speaking merchants took orders from the home market and then purchased diamonds in Antwerp. They bought smaller stones aggregating eight, ten, 15, and 20-carat parcels and sent them to India by post for sale. Indian artisans were talented in cutting, polishing, and setting stones because of India’s history of diamond mining, especially in Panna and Golconda, the latter in the Princely State of Hyderabad and famous for the Kohinoor Diamond from where it was mined.

Antwerp reclaimed its role as a global diamond trading hub[6] after the First World War when the importance of Amsterdam waned.[7] Large supplies of gem-quality stones from South Africa were traded in the Diamantclub Van Antwerpen bourse. The De Beers mines in South Africa were operational in 1880, but it was two decades later when Ernest Oppenheimer entered the mining business and dominated mining, first in German South West Africa (Namibia) and then in 1926 through a seat on the De Beers board in 1926, becoming Chairman in 1929. It was the old Diamond Syndicate and, later, the Central Selling Organisation (CSO) headquartered in London,[8] that strengthened the De Beers monopoly in every facet of the global trade.[9] Plentiful and steady supplies of gem-quality roughs from these mines made their way to markets in Europe.[10]

The Antwerp bourses were the gateway to European markets like Paris and London and the US market in New York. The profits made by the Jain merchants were on the value addition done by Indian workers back home to the small roughs that European manufacturers would not touch because of high labour costs. The polished stones were then resold in Antwerp and India. The Indian merchants sent the smalls to India in postal packages – Surat, Navsari, and Bombay were centers for cutting and polishing then. Some diamonds were absorbed by the Indian market, although gold jewellery was still the preferred choice for the common man. The diamonds were returned by post or carried in person to Antwerp. The beginning of postal flights to and from Bombay starting in 1932 helped reduce the time to send diamonds between the two cities.[11]

The Jains were attracted by the opportunities Antwerp offered despite the daily challenges of living so far from their culture. Not only were they vegetarian, but they did not eat anything growing in the soil like potatoes, onions, garlic, and carrots – all staples of European cuisine. But they built a strong support system within their community in Antwerp. The bonds of the Palanpuri Jains, both overseas and in India, are legendary. It is underwritten by close familial relations and the very nature of their business whose prerequisite is trust. Trade information and capital are circulated only within a closed network.

The Great Depression, beginning in 1929, hit the diamond trade badly. Supply outstripped demand due to the unregulated competitive selling of stones by mine owners after the First World War.[12] The few Palanpuri Jain diamantaires then residing in Antwerp, like Chandubhai, Suresh Mehta’s father, returned home before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

The war disrupted the diamond trade between Bombay and Antwerp, and it was only revived in 1945 when the war ended. It marked the beginning of a new phase of the trade because soon after India’s Independence in 1947, the next generation of Palanpuri diamantaires resumed their adventurous travels, testing the growing overseas markets further afield of Antwerp, of New York, Tel Aviv, and Hong Kong. These markets grew conterminously with Bombay’s diamond market from the 1950s. But Antwerp’s bourses never lost their primacy during these years of growth and till today.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

Support our work here.

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

©Copyright 2024 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] The milestone of a century is based on the presence of a small community of Palanpuri Jain diamond traders being present in Antwerp in the year 1925. The early pioneers arrived about 1920.

[2] The author uses the term last Nawab of Palanpur in the sense that His Excellency was the last Nawab to be coronated.

[3] The backdrop for this group photograph of only the men is the entrance to the original building of Diamantclub Van Antwerpen or the diamond exchange, then unincorporated in 1928.

[4] The Nawab and his predecessors were much loved by their Jain subjects because they ensured peace and stability, as far as they could, in their kingdom, and this combined with liberal economic policies allowed this community to flourish in various businesses and professions like grocery merchants, Ayurvedic vaids (experts in Ayurveda), photography. A few Palanpuri Jains were jewellers then but diamond trading did not define this community’s history as it does today. What is significant is that they have a legacy of being ministers, treasurers, and financiers in the royal court.

[5] Mehta, Jitendra C., and Amrit Gangar, Fragrant Folios: The Palanpur Story (Mumbai, Parikh Foundation and Mahendra Brothers Exports Pvt. Ltd., 2021), p. 21.

[6] Antwerp as a diamond trading and cutting center became dominant after the First World War, this was despite Belgium being a battleground during this War while The Netherlands remained neutral and unscathed. During the War, the supply of diamonds was adversely impacted, however, many merchants and cutter-polishers from Antwerp sought refuge in Amsterdam.

After the Armistice on 11 November 1918 that ended the War on the Western Front, most of these diamond traders and manufacturers returned to Antwerp, and additionally, Amsterdam’s merchants and manufacturers too shifted operations there because of lower wages and a more conducive social climate. Most of these traders and manufacturers were Jews during this period. The rise of Antwerp in the 1920s coincides with the arrival of the pioneering Indian diamantaires there.

One indication of this shift is the number of workers employed in manufacturing (cutting and polishing). In 1908, The Netherlands had 9000 workers, Belgium 4000, and India 600. In 1920 The Netherlands had 11,000, but Belgium had 14,000, and India had 1400. In 1929, the year that marked the beginning of the Great Depression, The Netherlands had 6000, Belgium 25,000, and India 200.

Berman, Mildred, The Location of the Diamond Cutting Industry (United States, Annals of the Association of American Geographers Volume 6, 1971) pp. 321-22.

[7] Antwerp was a center of the diamond trade as early as the 16th century when the trade in diamonds and its processing shifted from Venice because of the discovery of the direct sea route by the Portuguese to India, which shifted the trade from Venetian merchants to the Portuguese. The Portuguese preferred to trade in Antwerp where they sourced their imports to the East and sold their export commodities including diamonds. Diamonds were sourced by the Venetians, and later by the Portuguese, from the Indian Subcontinent, later Brazil, and then from the 19th century from Africa. However, Amsterdam was the bigger market in the 19th century till the First World War.

Grynberg Roman, Letsema Mbayi, Eds., The Global Diamond Industry: Economics and Development (UK, Palgrave MacMillan,2015) p. 22

[8] Today popularly known as Diamond Trading Company or DTC.

[9] De Beers S.A. Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/money/De-Beers-SA#ref131490

[10] The South African and Namibian mines were known to yield a large percentage of gem-quality roughs vis a vis the industrial-quality diamonds known as borts.

[11] Bombay was the main port of dispatch and receipt for postal packages on the Subcontinent’s west coast.

[12] A series of strikes in mines in German South West Africa, Angola, Belgian Congo, and Sierra Leone, added to the instability of the markets. This resulted in the organization of the trade under the leadership of De Beers, the largest supplier, by the formation of the Central Selling Organisation (CSO) headquartered in London. CSO regulates supplies and prices for both industrial and gem-quality stones.

See: Berman, Mildred, The Location of the Diamond Cutting Industry (United States, Annals of the Association of American Geographers Volume 6, 1971) p. 320.