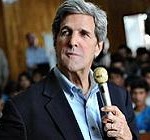

U.S. President Barack Obama has nominated Senator John Kerry to be the next U.S. secretary of state, a man who, it would seem, is to the job born – east coast, upper crust, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Vietnam vet, son of a diplomat, speaks French and likes global trouble-shooting.

As a former presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, he has added cache. The patrician senator is viewed as a foreign policy “nerd” for his tendency to go deep into issues. His 27 years on the foreign relations committee are proof of his abiding interest in world affairs. He clearly won’t need any job training as America’s chief diplomat but still have big shoes to fill – Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is popular both at home and abroad.

Kerry has already emerged as a significant actor in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region over the past three years when he went to repair breaches at the toughest of times. He worked out “understandings” and face-saving compromises, providing necessary cover for both sides to resume business.

His proximity to Pakistan’s leaders has raised some concern in India but it is important to remember that foreign policy is broadly made in the White House, where a larger vision of US strategic interests prevails. It is also true that Obama wants a peaceful exit from Afghanistan by 2014 for which he needs Pakistan. The price of Pakistani cooperation is usually paid by putting limits on India.

For instance, after the 2008 Mumbai attacks, Kerry, while on a visit to New Delhi, had the right idea in expecting Pakistan to take action against Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad, both of which were linked to terrorist attack planned in Pakistan. It can’t be business as usual, he had said then. But over time, he talked more about Pakistan being a victim of terrorism and he began working closely with the late Richard Holbrooke, the Af-Pak special envoy.

Holbrooke, who was appointed by Clinton but disliked by Obama and his staff, envisioned a new kind of relationship with Pakistan but he had few allies in Washington. He sought out Kerry, who shared his zeal about transforming the client-master relationship. The result was the grand Kerry-Lugar bill of 2009, which allotted $7.5 billion in aid to Pakistan over five years.

Kerry is expected to be confirmed by his senate colleagues after Obama’s second term is inaugurated and a new US Congress comes into session. But there is an undercurrent of criticism from the neo-conservatives in Washington about his past advocacy on behalf of “undesirable” world leaders.

Hawkish senators are likely to quiz Kerry about Syria, a country he considered an important player for the U.S. to patronize. Before Syria exploded into civil war, Kerry visited the country at least twice in 2009 and several more times till 2011 to meet President Bashar al-Assad. After one such trip during which Kerry took a motorcycle ride with Assad, he called him “my dear friend” upon his return, an endearment that is being repeatedly cited in various conservative fora and held up for ridicule.

Kerry championed greater engagement with Syria in the early part of the first Obama administration, calling it “an essential player in bringing peace and stability to the region” and a “key” to reviving the Middle East peace process. In a speech at the Carnegie Endowment on March 16, 2011, he even called Assad “generous” and expressed his belief that the country would change in the right direction as it benefits from a relationship with Washington. Ironically, the Syrian “revolution” had started a day earlier on March 15 with the “Day of Rage” and simultaneous protests in major cities across the country.

Kerry’s belief in engagement can’t be faulted – but his assessment of Assad as the man to lead a new Syria lies shattered. Now, one of Kerry’s first foreign policy challenges will likely be designing moves against his former interlocutor.

Kerry is also a popular figure in Pakistan for his intervention in creating possibilities for a rapprochement. Most Pakistanis appreciate the Kerry-Lugar bill for funding key development projects and keeping them alive.

Even though the law has requirements that the Pakistan army must not subvert the civilian government and cooperate with the US in counterterrorism, Clinton waived the process last year and granted Pakistan a waiver on that requirement despite evidence to the contrary. The waiver was yet another effort to assuage Pakistan and ensure cooperation for US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014.

Kerry has advocated continued aid to Pakistan even when many of his Senate colleagues have loudly questioned Pakistan’s integrity in clamping down various terrorist networks operating from its territory. He is believed to have a positive opinion of the Pakistan army and enjoys good relations with the top brass.

Kerry went to Islamabad to assuage the anger and listen to Pakistan Army Chief Gen. Ashfaq Pervez Kayani a few days after the raid on Osama bin Laden on May 2, 2011 when bilateral relations were at an all-time low. In the process he convinced Kayani to return the tail of the US military helicopter that went down during the raid. While the Navy Seals had destroyed the body of the helicopter to prevent technology from leaking out, the tail had remained intact. China was already moving to get access to it. While there, Kerry also worked on a “road map” of specific steps and issued a joint statement, which stated that the US had no designs on Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. He was willing to “personally affirm such a guarantee.”

There is no doubt that Kerry has been a key player in moderating America’s turbulent relationship with Pakistan, often playing the ‘good cop’ to Obama’s ‘bad cop,’ to Clinton and other senior US officials who regularly blame Islamabad for playing a double game.

When Pakistan shut down the NATO supply routes in retaliation for the killing of 24 Pakistani soldiers in a US air raid on November 26, 2011 near the Afghan-Pakistan border, Kerry was part of the diplomacy which ultimately led to the reopening last summer after seven months.

The process apparently included a quid pro quo about accommodating Pakistan’s “concerns” on Afghanistan, which essentially center around limiting India’s role. The new peace plan reportedly worked out by Kayani and Afghan President Hamid Karzai currently in circulation for a post-2014 Afghanistan, is all about Pakistan’s eminence in “managing” the political dispensation and the American acceptance of the idea, however reluctantly.

It should come as no surprise that Kerry’s nomination was greeted with enthusiasm in Pakistan. The Express Tribune captured the sentiment in an editorial on Dec. 26 last year when it said: “Pakistan has reason to like him.” When relations went south, Kerry was seen “as a friend of Pakistan… He continued to emphasize the Pakistani point of view while putting forward the concerns of the Obama Administration.”

In the end, it is worth noting that US-Pakistan relations oscillate between bad and worse and are dependent on personalities. US-India relations are stable and more or less institutionalized with regular contacts and working groups.

In the future, it will be less about Pakistan and more about India. When Kerry works on the U.S. pivot to Asia – a major plank in Obama’s vision of the future – India will be front and centre, along with China.

Seema Sirohi, an international journalist and analyst, is a frequent contributor to Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Seema is also on Twitter, and her handle is @seemasirohi

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2013 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited