This is part of an article series on India in the Global Commons. Click here to read the entire collection.

Increasing computing power will drive a massive technological revolution over the next 20 years. Many of the changes will be beneficial: they will help society grapple with an aging population, offer consumers more choice, increase energy usage efficiency, transform rural economies and facilitate distributed transactions and record keeping.

Yet, despite these and other benefits, there is a significant risk of such changes making most people worse off than their parents. Artificial Intelligence, and robotics, in particular, will reshape the labour market by changing the relative contributions from different factors of production.

Although specific scenarios are unknown (and unknowable), two aspects about the advanced technologies era are clear. First, they will be driven by proprietary knowledge, that is, Intellectual Property (IP). Since this IP is generated within a few countries only, and even there, by a very small number of individuals and firms, income and wealth distribution will worsen before it improves (eventually, if at all). Second, big data and the robotics it drives will transform discussions around work and leisure, and the uses that such data has.

Governments will require an arsenal of policies[1] they might deploy in a wide range of areas to counter the economic, social and other impacts of the application of big data.

Transformative technologies

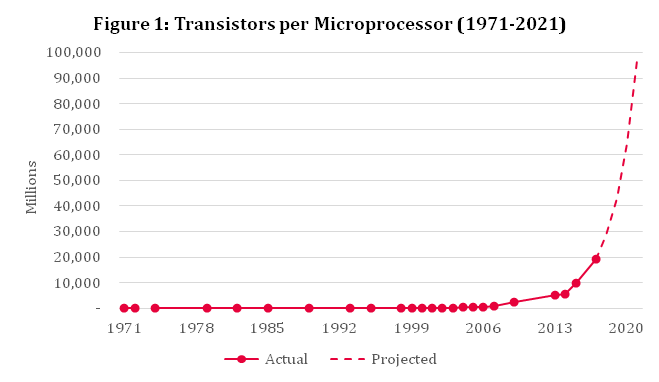

Moore’s Law, the observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit chip doubles roughly every 18 months (and hence, also computing power per dollar), has proven to be remarkably reliable over the decades and across numerous different semiconductor fabrication technologies. Yet, its broader implications may only now be starting to be felt in earnest. Whereas in the 1960s a doubling of computing power implied a very small absolute increase in the number of operations per second, today it implies a very large increase, and hence, a large impact in terms what becomes technologically feasible (see Figure 1).

In no field is the impact of growing computational power more apparent than in AI. Many of the basic algorithms that underlie today’s AI were developed decades ago, but were not feasible solutions to real-world problems at that time in the context of the state of the art in computing. Consequently, robotics has made impressive leaps in the last decades. Until recently, robots were inflexible machines that were very good at accomplishing a single, well-defined, repetitive task. But that too is changing, with the newer generation of robots being better able to handle non-routine jobs, thanks in part to the guidance of AI. Robots could soon start to perform tasks, such as housekeeping, gardening, surgery, and even construction.

Policy responses

The list of policy actions governments will have to consider in the age of robotics is wide and deep; many are already on the front burner, nationally, and in multilateral fora, such as the G20. An abbreviated list includes the following:

Competition and tax policy: Advanced technology firms accrue economic rent in two related ways, viz. via the monopoly power granted by IP systems and first-mover advantage. The recent crises around data firms have accelerated the trend to view them not as special, but as natural monopolies. Viewed in this light, the policy responses are:

- competition/anti-trust legislation;

- taxing rents from IP (which raises inter-jurisdictional issues); and

- addressing an eroding tax base (leading to the literature on raising revenues to produce global public goods, the modern manifestation of which is the proposal to “tax robots”.)

Maintaining aggregate demand: It is likely that wider use of robotics might usher in a prolonged period of marked deflation and a radically altered labour market wherein long-term jobs as we know them give way to temporary and piecemeal work. This, in turn, raises the following possibilities:

- rethinking the social safety net (for example, making pensions more portable or disconnecting pension schemes from firm-level employment);

- moving towards a Universal Basic Income;

- using “helicopter money” to stabilise prices.

Governance of new technology:

- ethical standards for emerging technologies;

- accountability and transparency for algorithms;

- adapting existing regulatory and legal frameworks for independent workers.

Education and skills training:

- rethinking pedagogy (for example, lifelong learning rather than “front-loaded” education);

- curriculum (re)development (promoting STEM training while also recognising the importance of the humanities, along with focus on computer literacy and coding as core parts of basic education);

- training for inter-disciplinary adaptive skills;

- fostering entrepreneurial mindsets.

Balancing privacy with public security: What is the right balance to strike between privacy and security in a data-driven world? This critical question is one that several countries are asking themselves and that needs to be determined in light of each one’s particular legal, socio-cultural and governance background.

India’s Personal Data Protection Bill 2018 attempts to set this balance right and threats to privacy and security continue to evolve alongside emerging technologies. But the following approaches will aid in periodically assessing the priorities at hand:

- raising awareness of the opportunities and risks associated with digitisation, particularly in the rural areas, and of new legislations, policies and mechanisms of recourse;

- creating ongoing platforms for open engagement with stakeholders – including the technology sector, privacy advocates, and key officials from relevant government agencies – on the risks, challenges and opportunities that emerging technologies pose, and focusing on developing practical solutions in real time;

- having a flexible governance framework that can anticipate and respond swiftly to privacy and security concerns;

- Robust monitoring[2] and implementation of upcoming policies and legislation that balance privacy, security and innovation.

The mix of national and international dimensions of the policies will vary, but India has a leading role to play here – if it wishes to. India’s response to this data revolution[3], where it is relying not only on legislation and policy, but technology-enabled solutions, has already been recognised as forging a new path forward. It can be a role model for other developing countries in social democracy, particularly in how it leverages this era to create inclusive economic growth. As a major emerging power, it can participate in global norm-setting and rule-making.

Rohinton P. Medhora is President, the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Canada. Rohinton is also on twitter, and his handle is @RohintonMedhora.

Samane Hemmat is Research Associate, International Law Research Program, the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Canada.

This is part of an article series on India in the Global Commons. Click here to read the entire collection.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References:

[1] Blit Joel, Samantha St. Amand, Joanna Wajda, ‘Automation and the Future of Work: Scenarios and Policy Options’, CIGI, 174, 29 May 2018

[2] Slaughter Anne-Marie, Stephanie Hare, ‘Our bodies or ourselves’, Project Syndicate, 23 July 2018, <https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/dangers-of-biometric-data-by-anne-marie-slaughter-and-stephanie-hare-2018-07>

[3] Vora Priya Jaisinghani, Matt Homer, Kay McGowan, ‘Is the World’s Largest Democracy Creating the First ‘Data Democracy?’, Medium, 9 May 2018, <https://medium.com/emerge85/is-the-worlds-largest-democracy-creating-the-first-data-democracy-75868d6c091e>