A nine-day trip, organised by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a select group of Indian scholars, was a privilege and an eye-opener. In three cities – Beijing, Chengdu, Kunming – we interacted with a range of universities, think tanks, scholars and officials.

China is now a developed country on most visible parameters. Its infrastructure build-out is complete, the citizens are educated, well-dressed and healthy, with youth being taller than their parents. By most standards, China has achieved its dream and is on top of the world.

So it came as a surprise to find that in all the three cities, Chinese scholars were uniformly concerned on three issues: the alliance in the Indo-Pacific which they see as antithetical to China’s interests; India’s refusal to join the Regional Economic Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP) and India’s economic slowdown.

China seems genuinely spooked by the trade war with the U.S., which seems to indicate a strategic break with the world’s (still) largest economy. This also dovetails with China’s concerns about India’s refusal to join the RCEP and India’s potential role in the Indo-Pacific.

The RCEP is a proposed economic bloc that would have included China, Japan, the ASEAN countries and India, but which India refused to be part of. Chinese scholars worried that India’s staying out of the RCEP means reduced access for their products by another large economy, which could make up for the loss of exports to the U.S.

The break with the U.S. is not just economic, but also strategic – which reflects China’s angst about the Indo-Pacific. It worries about an alliance of the major democracies (U.S., Japan, India, Australia) of the region, aimed at containing China. A scholar in Beijing was quick to point out the hazards of allying with the U.S., stating colourfully that “The U.S. may cook India like a frog in warm water,” and that India will be bound to the U.S. In their bipolar world order, there is little appreciation for India’s own strategic autonomy and long-term commitment to an international rules-based order.

About its own strategic initiative, viz. the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China seems subdued. Chengdu is the largest city in Western China, and highly industrialised, especially in the auto and aircraft sectors. It expects to play a significant role in the BRI. There is a lot of traffic between Beijing and Chengdu – the flights are full and the aircraft are wide-bodied, rare for domestic flights anyway. With BRI plans being scaled down in Malaysia, Myanmar and Pakistan, there is recognition that “the political must be separated from the economic” – a tacit acknowledgement of the unviability of some past investments.

Can a less-ambitious, more viable BRI be in the works?

The last stop was Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province in southern China. Although a Tier-II city, the infrastructure rivals that of any global capital’s. As in the rest of China, the government plays a large role in business, including in luxury hotels, airlines and real estate. And they deliver – these hotels are as good as any five-star in the world. Kunming is closer to Kolkata than to Beijing – the proximity is strategically acknowledged by the multitude of South Asian study centres in Yunnan University.

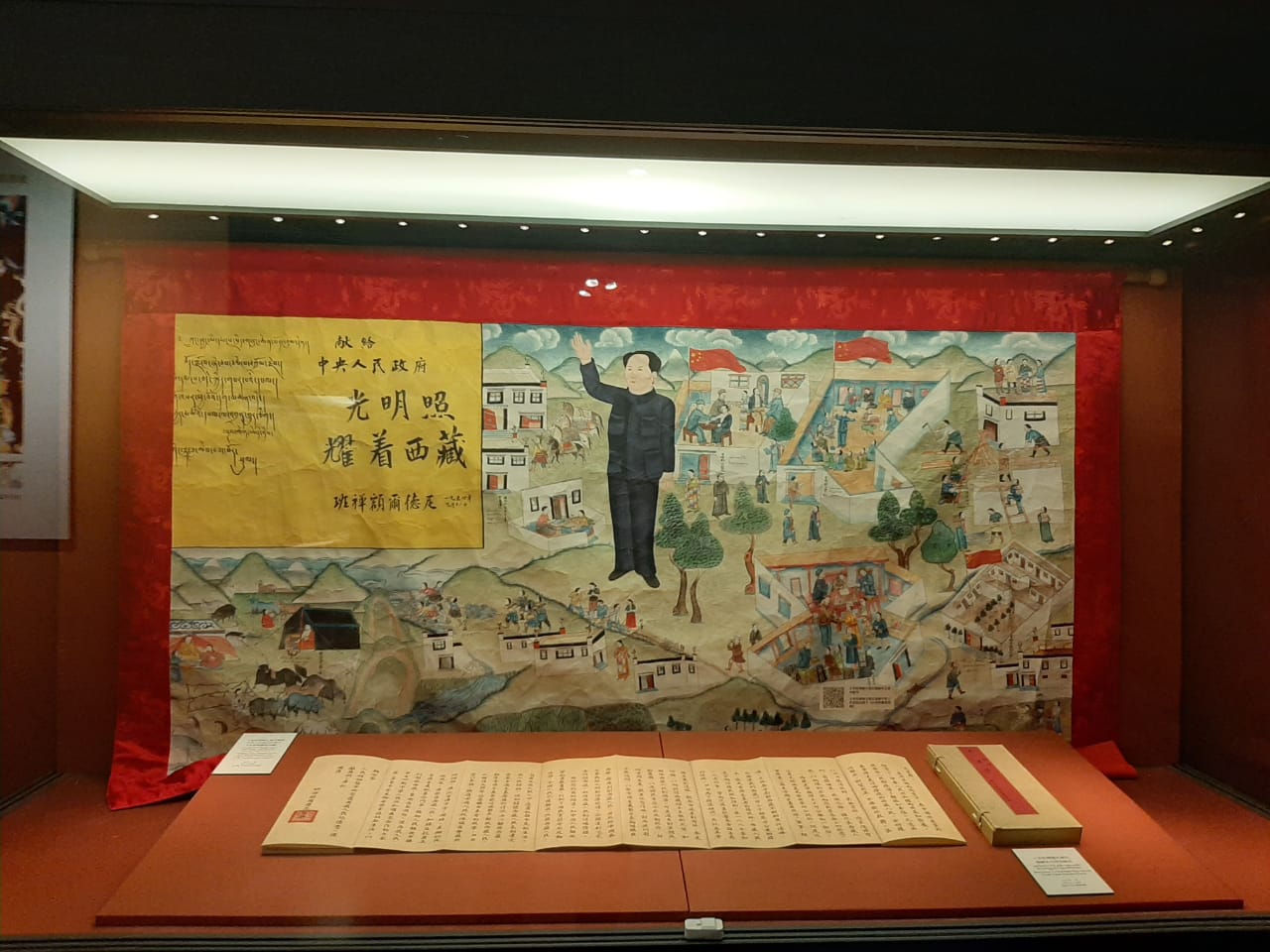

Of course, Tibet was under discussion. The first official engagement of the group was to the China Tibetology Research Centre in Beijing, an institution devoted to the study of Tibet’s economy, culture, religion and politics. Visitors are on a walk through the centre’s museum to view the “Exhibition on the Reincarnation of Tibetan Buddhist Living Buddha”. The exhibit aimed to show that all the 1,400 Tibetan lamas, who have been reincarnated, have always required ‘approval’ of the Central Government – the Chinese emperor in the past, and now, the Chinese Communist Party. Communist Party officials officiate in the selection of the reincarnations of lamas who are still in Tibet – this is also a part of the exhibition.

The exhibit is important for China because His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the spiritual head of the Tibetan nation, is now 84 years old, and the issue of succession is relevant. By selecting the new Dalai Lama, China can co-opt the most powerful symbol of Tibetan resistance.

Amit Bhandari is Fellow, Energy and Environment Studies Programme, Gateway House.

This blogwas exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.