The Russia–Ukraine conflict and its impact on supply chains and routes have enhanced interest in Central Asia, which is key to cross-continental trading routes. Many of the countries in the region are constructing or supporting new rail links and upgrading old ones, independently, with multilateral funds and with significant Chinese investment in rail connectivity projects to and through Central Asia.

More are on the agenda. For instance, on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Summit in Samarkand in September 2022, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan agreed to jointly fund a feasibility study for the route of the proposed China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan rail line in Kyrgyzstan. This will create connectivity to Afghanistan via the Uzbek–Afghan border at Hairatan.[1] Especially for goods that ply from China to Afghanistan, it will reduce delivery time from the current route via Karachi to Afghanistan from two months to two weeks. Similarly for goods traveling from China to Europe, it will cut transportation time and connect to West Asia via the new, under-trial International North South Transport Corridor that stretches from India to Russia.

The quiet and biggest beneficiary of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and western sanctions on Russia, is China which has deepened its engagement with the Central Asian countries, focusing mainly on infrastructure and development. Ten years ago, President Xi Jinping announced China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Kazakhstan. A decade later, this May the first China-Central Asia Summit was held in Xian, China. Xi emphasised the “new impetus to the development and revitalisation of the six countries” and the “strong positive energy [for] regional peace and stability.” The choice of Xian, the Chinese end of the Silk Road, for the Summit is significant.

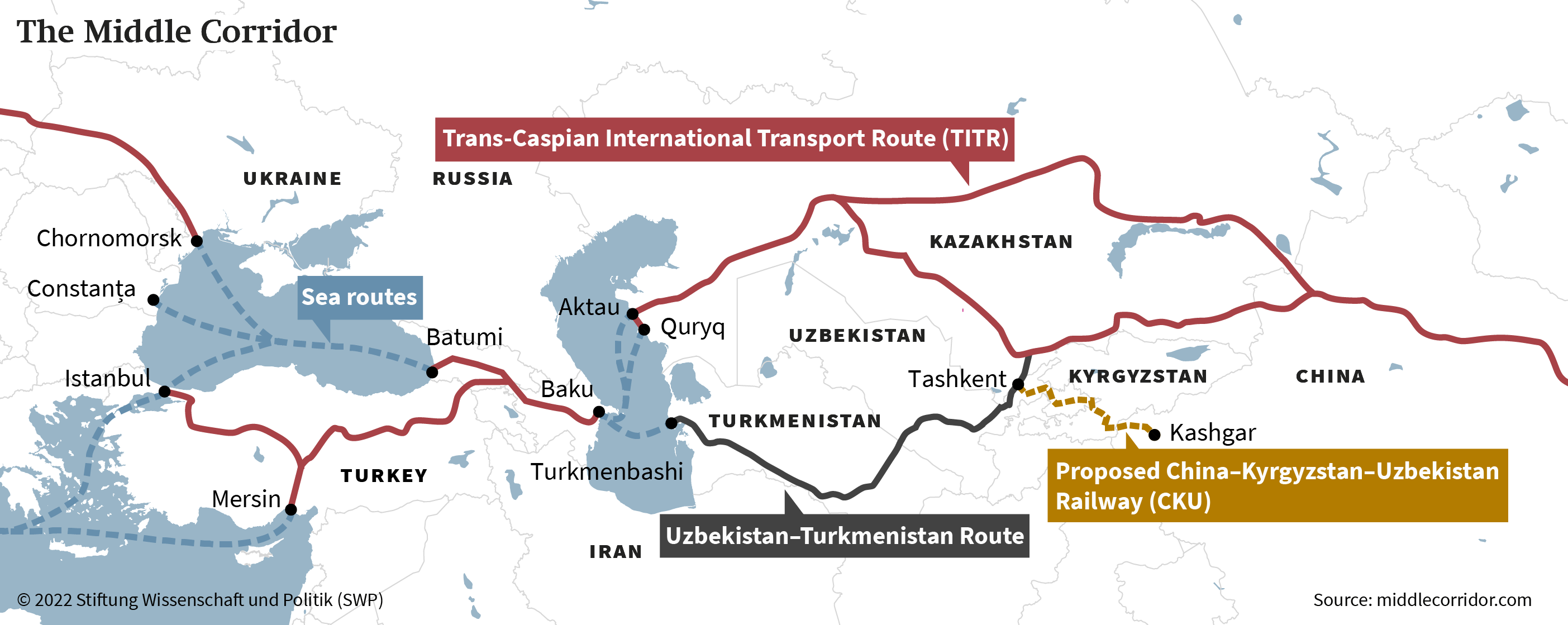

The western sanctions do not directly target the operations of the China-Europe Railway Express using Russian routes like the Northern Corridor, which connects the Pacific ports of Russia and China to Europe. But logistical delays, and the boycott by some western companies manufacturing in China have affected its operations. The Middle Corridor[2] including the Trans Caspian International Transport Route and other routes that run from China to Europe through Central Asia and the South Caucasus, Turkey and Eastern Europe, provides an alternative. Cargo shipments, from China, South Korea, Japan, and occasionally even from India, along the Middle Corridor were 3.2 million tons in 2022, compared to 530,000 tons in 2021.[3]

For Russia the Middle Corridor is a trade route competing with its own Northern Corridor. But at the moment it may be useful for its trade through other countries like Kazakstan, Armenia and Georgia. German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier during a visit to Kazakhstan in June described the Middle Corridor as an alternative transport route for goods between Asia and Europe, that is geared to the future. A company is being created by Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia to manage the unification of tariffs and handling of cargo transportation between China and Europe. The aim is to reduce delivery time from 15 – 19 days to 10-15 days.[4] Today’s global supply chain reconfiguration, the European energy crisis, and the EU’s desire to seek alternatives to the trans-Siberian railway freight routes, all provide the Middle Corridor countries with tremendous potential as markets and partners for the EU.[5]

Central Asia is also a gainer. As an end to the Russia-Ukraine conflict is not in sight, the EU is looking for more energy imports from Central Asia. German crude oil imports from Kazakhstan at 8.2 million tonnes in 2022, is 10% higher than the previous year, and will likely be stepped up in 2023 and beyond. Kazakhstan supplied 90,000 tonnes of crude to Germany through the sanctions-exempt Russian pipeline Druzhba’s southern branch during February-April 2023, replacing Russian supplies.[6] Kazakhstan also reached an agreement with Azerbaijan in early 2023 to annually ship up to 1.5 million tonnes of Kazakh oil through the South Caucasus, most of it bound for Europe.

On 25 May 2023, the U.S.-based Air Products signed a $1 billion investment agreement with Uzbekistan to own and operate a natural gas processing facility in Kashkadarya. Import of gas from Turkmenistan, most likely via Azerbaijan, also remains an option. Azerbaijan has entered into a gas swap arrangement with Iran and Turkmenistan as its domestic production is not enough to meet export commitments including to Europe, The Russia-Ukraine conflict may renew interest in financing a pipeline to supply Turkmen gas to Europe.

The Central Asian countries are keen to benefit from the resurgence in global interest in the region. An annual consultative meeting of the Heads of five Central Asian countries that was launched in Astana by the Central Asian leaders in 2018, for discussions on cooperation in trade and transport among other areas, is scheduled to be held in September 2023 in Dushanbe. They understand it is vital now to have political stability to attract investment and develop the region. Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have experienced unrest and protests last year. Their governments are focusing on governance, economic and social justice, and political stability. The Central Asian countries also together engage, with several major countries and with the EU in a “5+1” format, providing them the opportunity to coordinate their approaches and decisions for optimising benefits.

They still walk a fine balance, though. They make appropriate comments about the Russia-Ukraine conflict to keep the western countries engaged in seeking peace, and Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have voiced respect for Ukraine’s territorial integrity but their partnership with Russia remains largely intact. The Victory Day parade on 9 May in Moscow saw the participation of the leaders of all the Central Asian countries. Their economic, political, defence and security linkages with Russia are too extensive to see any drastic changes in their overall relationship.

Where then, does India figure in these conversations of the future? India’s relationship with Central Asia is robust and has consolidated and expanded in recent years. The Delhi Declaration of January 2022, when the first India-Central Asia Summit took place in virtual mode, prioritised connectivity projects. It was agreed to continue engagement for further development of the transit and transport potential of their countries, improving the logistics network and promoting joint initiatives to create regional and international transport corridors.[7]

More recently, at the virtual SCO Summit hosted by India on 4 July, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated that following Iran’s membership in the SCO, both can work towards maximizing the utilization of the Chabahar Port. The International North-South Transport Corridor, he said, can serve as a secure and efficient route for the landlocked countries in Central Asia to access the Indian Ocean.[8]

The India, Iran and Uzbekistan Joint Working Group on the use of the Chabahar port had its first meeting in December 2020. There have been trial runs along the INSTC since then, and all the countries along the route appear keen on its early operationalisation. Hopefully INSTC, conceived in 2002, 11 years before the BRI announcement in Kazakhstan, will soon achieve its objective of a trade route to Russia, Central Asia and other countries, saving costs and time. This improved physical connectivity will enable India to pursue its other regional objectives of trade, investment, services, technology more easily and connect directly with the Central Asian peoples.

Vinod Kumar is a former Ambassador of India to Uzbekistan and Permanent Representative of India to SCO-RATS.

Photo credits: The Middle Corrdor

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

Support our work here.

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

©Copyright 2023 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] “An Agreement on Cooperation Was Signed in Samarkand on the Construction Project of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway on a Section in the Territory of the Kyrgyz Republic.” 2022. http://kjd.kg/ru/press-service/news/full/1553.html.

[2] The Middle corridor comprises mainly of the Trans Caspian International Transport Route, but includes other routes and elements, such as the Uzbekistan – Turkmenistan route, and the Trans Caucasus Trade and Transit Corridor.

[3] Chang, Felix K. “The Middle Corridor through Central Asia: Trade and Influence Ambitions.” Foreign Policy Research Institute, March 9, 2023. https://www.fpri.org/article/2023 /02/the-middle-corridor-through-central-asia-trade-and-influence-ambitions/.

[4] “Air Flights Increase and Trans-Caspian International Transport Route Development: 10 Documents Signed during Visit of Alikhan Smailov to Azerbaijan.” Official Information Source of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2023. https://primeminister.kz/en/news/air-flights-increase-and-trans-caspian-international-transport-route-development-10-documents-signed-during-visit-of-alikhan-smailov-to-azerbaijan-24512.

[5] Elden, Tuba. “Russia’s War on Ukraine and the Rise of the Middle Corridor as a Third Vector of Eurasian Connectivity.” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), 2022. https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/russias-war-on-ukraine-and-the-rise-of-the-middle-corridor-as-a-third-vector-of-eurasian-connectivity.

[6] Abbasova, Vusala. “Kazakh President Says There’s Potential to Raise Oil Supplies to Germany.” Caspian News, 2023. https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/kazakh-president-says-theres-potential-to-raise-oil-supplies-to-germany-2023-6-2-58/.

[7] “Delhi Declaration Ofthe 1stIndia-Central Asia Summit.” Embassy /high commission /consulate General of India, 2022. https://eoi.gov.in/tashkent/?pdf13991%3F000.

[8] “English Translation of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi’s Remarks at the 23rd SCO Summit.” Press Information Bureau, 2023. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1937353.