At the last BRICS Summit held between Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa on March 29th in New Delhi, the development banks of the participating countries agreed on a proposal to extend credit in local currency for trade, project financing, and infrastructure projects.

So far, no clear mechanism on how participating countries will extend local currency credit has been announced. Some financial gurus even dismiss the BRICS agreement as purely symbolic. Yet banks in London, New York, Tokyo, and Singapore would be wise to take a second look at what now could be the most significant agreement in international finance since the Euro.

BRICS countries make up a massive trade bloc. Current intra-BRICS trade stands at $307 billion, set to reach $500 billion by 2015. Within BRICS, China is the dominant player, exporting nearly $135 billion in goods and services a year to its partners. India imports nearly $50 billion annually from China, and China accounts for 11.8% of India’s total imports, increasing its share of the Indian market by 2% just in 4 years.

This provides valuable insight on what kind of currency deal could be made in the future. As trade increases, it is possible that China will move swiftly to provide renminbi for importers of Chinese goods.

At this time, China facilitates payment in renminbi through a central bank liquidity swap. Since 2009, 16 countries have exchanged local currencies for a total of 1.6 trillion renminbi through these swaps; more are in line to participate. In a March 22 article published in the Financial Times entitled “China and Australia in $31bn currency swap,” Simon Rabinovitch and Neil Hume reported that Japan and Great Britain are rumored to be in queue for the next Chinese central bank swap. But after the Delhi meeting, China’s BRICS partners may leapfrog to the top of the list.

From the BRICS, Russia is currently the only country that swaps its currency with China. It seems obvious that India, Brazil, and South Africa should do the same.

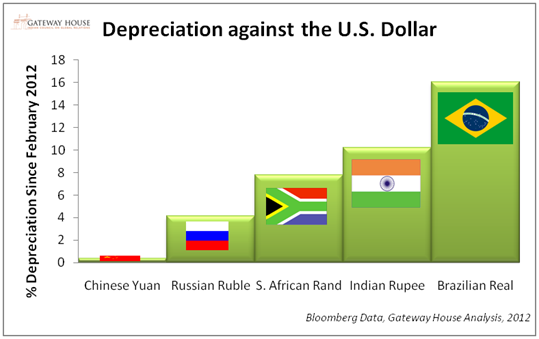

Four factors make a central bank liquidity swap particularly important for these four BRICS partners. First, BRICS countries are losing purchasing power because of depreciation against the dollar.

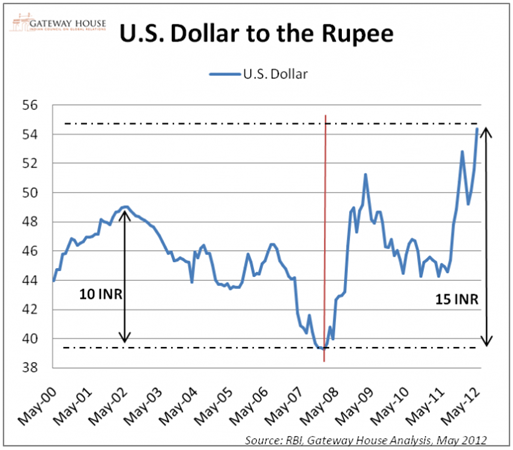

The dollar accounts for 40% of global foreign exchange trade. The BRICS, hungry for goods and services to fuel their emerging economies, depend on the dollar to pay for imports. But it’s getting harder for BRICS to buy dollars. Brazil has seen its currency depreciate by over 16% since February 2012 and the Indian rupee has fallen to an all-time low of 56.51 to the dollar on Thursday, losing more than 20% of its value in the last 12 months. To finance imports, India is paying more for dollars than it has done in over a decade. India can benefit from a Chinese swap arrangement to hedge against fluctuations in the currency market.

Second, following the 2008 financial crisis, rupee-dollar exchange rate volatility has increased by as much as 50%, making it more difficult to predict the cost of dollars in the currency market.

This uncertainty places India in a tough situation, given the rising prices for key commodities like crude oil, a slowdown in capital inflows, and the current account deficit, now at a decade low of -4% of GDP. India isn’t alone – Brazil and South Africa are facing the same problem as their currencies have seen deviations of up to 25% to the dollar. Their current account deficits too are high, at -2.1% and -3.4% of GDP respectively.

Third, there is an opportunity to save on the transaction costs. Exchange rate transactions for Indian business can typically cost up to 1%-2% of a deal. In BRICS New Delhi Summit 2012, the inaugural publication of the BRICS Research Group, Vladimir Dmitriev, chair of the Russian development bank, suggested in an article entitled “Plenty to gain from strengthening financial links among BRICS” that trading participants will save up to 4% by entering into these agreements. Participating countries could alleviate the burdens of transaction costs, financing fees, and currency fluctuations. Quick math shows that at full potential, BRICS countries save $12.3 billion a year in banking services. Based on its share of trade with BRICS countries, India could save $2.3 billion annually from entering into such swap arrangements.

Lastly, a central bank liquidity swap will benefit small business. With the credit rating agencies such as S&P downgrading India, it has become harder to get dollar loans at reasonable interest rates. This is especially true for small and mid-cap companies which do not have large balance sheets or a long credit history to defend the loan requests – and it is these companies that are likely to be the backbone of increased intra-BRICS trade between. Drawing on a swap line from China, the Reserve Bank of India can offer attractive loans to businesses through the Export-Import Bank in renminbi, to finance Chinese deals. At the government level, swaps can guarantee the mode of payment without having to worry about inadequate dollar supply.

There is geopolitical risk in this however.

India entered into a similar currency agreement with the former Soviet Union. In the late 1950s, India did not have the institutions and capacity to facilitate large-scale foreign exchange transactions. So, Russian exports were paid for with non-convertible rupees, which were used by the Russians to purchase Indian goods like tea, jute, and other commodities.

For Russia and India, the principal motive for rupee-denominated trade was to facilitate arms deals. India’s defense imports from Russia prompted a large trade deficit. The RBI reports that from 1961-64, India tripled its trade deficit with Russia, from 13.1 to 45.5 crore rupees. This trade relationship has stood the test of time. Since then, Russia has supplied India with over $35 billion in arms. In 2012, Russia is expected to supply $7.7 billion in arms to India, about 80% of India’s total arms imports.

Because of the trade deficit, the Soviet Union accumulated rupees it didn’t need. From 1955-76, Russia accumulated upwards of $350 million in non-convertible rupees. As the rupee holdings accumulated, Russia sought a strategic advantage from its poorer trading partner.

Firstly, redundant imports like Indian tea were re-exported by Russia to Western markets. From 1958-60, because of this trade diversion, or ‘shunting’, the Indian Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics reported that India lost up to 20% in signature commodities sold to developed countries.

Then, in the 1960s, Moscow also asked for naval base rights in Indian ports. To avoid setting a precedent, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi refused to buckle under pressure from the Russian Navy, believing that the quid pro quo would also threaten regional security in the Indian Ocean. Though national autonomy was not compromised

, India learned an important lesson having been on the receiving end of geopolitical pressure from its trade partner.

As with the Soviet Union then, so is the possibility with China now.

Given the lessons from its past with Russia, India should be concerned with the growing trade deficit with China, estimated to reach $60 billion by 2014-15. If it enters into a similar currency agreement, India can expect trade diversion, geopolitical pressure, and a long-term commitment with its trade partners.

In negotiating its rupee relationship with Russia, H. V. R. Iyengar, then Governor of the RBI, wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, warning him of the dangers of such currency arrangements. Nehru ignored the Governor’s judgment, declaring that, “political compulsions far outweigh economic considerations.”

A half a century later, India’s motives are economic. BRICS swaps make sense – they save money on imports by freeing India from currency fluctuations and reduce the cost of funds, providing liquidity that businesses require in a tough financial environment. The key for India will be to negotiate favorable terms of agreement. Only then will India’s economic advantages outweigh the geopolitical risks of such a deal.

Samir N. Kapadia is a Researcher at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

A shorter version of this article appeared in Mint, a national daily newspaper. You can find more Gateway House features here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2012 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.