This is the final in our two-part series on India-Afghanistan relations. Click here to read the second part.

Better connectivity means better business and Mumbai’s Pathan community is set to benefit from a few measures, designed to enhance the India-Afghanistan bilateral. In January 2018, India took over operations of part of the Shahid Behesti Port (Chabahar, Iran).[1] It has also completed the 218-km Zaranj-Delaram road and rail corridor, leading to Afghanistan’s capital city, Kabul, from the Iran-Afghanistan border. Trade between India and Afghanistan totalled $1.143 billion in 2017-18,[2] while the new port and road-rail corridor will also be India’s gateway to Central Asia and Russia.[3] Numerous direct freight flights have also been begun recently.[4]

These routes, which bypass Pakistan, are of geo-economic importance to both countries: India is the largest market for Afghan products in the neighbourhood. The traditional dry fruit and saffron trade – import, wholesale and retail – that the Pathans have historically been engaged in continues to constitute 62% of total trade in 2018-19.[5] In recent years though, Pathan businessmen have found the import-export business in gemstones – lapis lazuli, rubies and emeralds – also proving lucrative.[6]

These new corridors may well help Mumbai’s Pathans grow their businesses, but they do not make their visits home easier as they do not engirdle their ancestral homeland. Most members belong to tribes from the mountainous terrain of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPP) and the northern regions of Baluchistan, which are all part of Pakistan.[7] With India’s relations with Pakistan spiralling only downwards, many of the city’s Pathans, who have opted for Indian citizenship, are finding it increasingly difficult to get visas to visit their families and look after ancestral properties back home.[8]

“Earlier Pathan tribes on either side of the Durand Line border between Afghanistan and British India could travel freely,” says Yakub Khan (Yusufzai), General Secretary, Anjuman-i-Pukhtoon Trust, which was established in 1942. “Traders, labourers, visiting relatives and brides, would cross this border. Even after India’s partition, it was relatively easy to enter India from Pakistan and vice versa, till recently.” Khan adds that although he was born in India and holds an Indian passport, he travelled like most of his brethren in the city, to his home village in the Afghan belt of Pakistan to get married and bring his bride back to India. A tradition that continues to date.

Reverse migration occurs too. A Bombay-born and raised Pathan recently married two of his daughters into families settled in Karachi and Kabul. The community’s centuries-old transnational network is therefore as active as it ever was, facilitating a way of life, especially the preference to marry within the tribe.

Mumbai’s cosmopolitanism and the Pathans’ multi-generational presence in the city, dating back almost 250 years, have not diluted many of these social mores. Older Pathans may be products of a secular education from the city’s English-medium convent schools and have daughters with post-graduate degrees. But as a patriarchal society, reservations remain about permitting them to work. Tribal loyalties – more than religious orthodoxy – hold the Pathans together, as their history in the city and the region’s larger context show.

Pathan tribes in Bombay

The Pathans make up the world’s largest tribal population. In Bombay, the dominant tribes are Yusufzai, Hasanzai, Durrani, Shah, Ahmadzai, Kakkad and Afridi. With the exception of the Durrani (formerly named Abdali) tribe, hailing from the central plains of Afghanistan and to which many Afghan kings belonged, all the rest originate from regions that comprise the tribal belts of Pakistan. And there is a reason for this.

The tribes that came under the influence of the Indian subcontinent lay east of the Durand Line[9] and west of the Indus River, a natural marker for the beginning of Pathan terrain: they were the Eastern Pathans who came from the Peshawar Plain and valleys to its north, as well as highlanders from the mountainous regions of the Pamir, Hindukush and the Sulaiman, who speak Pushto or its northern, gruffer variant, written in the Dari script.[10] Those to the west, came under the Persian influence and speak Dari, a variant of Farsi.

Yet another aspect of their identity is the belief in their Biblical roots. Despite their homeland being dispersed across what is today’s Afghanistan and Pakistan, the tribes are allied together by descent from a common pre-Islamic ancestor, named Afghana. Pashtun oral tradition says that he was the grandson of King Saul of the Biblical Kingdom of Israel. By 1000 A.D., most tribes were converted to Sunni Islam, but this conviction in their Judaic origins and belonging to one of the Lost Ten Tribes of the Kingdom of Israel, known as the Beni Israel, persists.[11]

This combination of oral history, a maze of tribal genealogies and feuds,[12] and the realities of history – since their homeland has been a zone of conflict and situated at the crossroads of trade, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor running through Pathan villages – makes them hardy as a people and the need to maintain their cultural identity urgent.

“We like to be low-key, and just want to maintain our culture, religion and way of life wherever we are,” says Bedar Khan (Hasanzai), whose grandfather and sibling were the first in his family to come to Bombay. “We Pathans do not involve ourselves in politics. Almost all of us have family in KPP in Pakistan and on the other side of the border in Afghanistan.” Misunderstandings can occur when news gets disseminated through their strong transnational feudal network, often with some distortion of facts. Hence, most Pathans tend to be secretive even within their immediate families about business, in particular, to guard against jealousy, extortion and tribal feuds back home in their ancestral villages.

Anchoring this strong clansmanship is a tribal (customary) code of conduct called Pukhto or Pashtunwali[13], which may have variations from tribe to tribe. Broadly, this code embraces universal values, with some fundamental ideals of individual and collective behaviour unique only to the Pathan. These include honour, hospitality and the concept of reciprocity (not mere revenge). “The world does not understand this quality,” says Yakub Khan. “Pukhto, for us, is a law. It also enjoins us to be patient, friendly, loyal and patriotic.” On a community level, all inter- and intra-tribal disputes, even in Bombay, are resolved by constituting a council of elders, known as a Jarga. But in reality, an acknowledged community leader is often effective in running community affairs.

“When the underworld don Karim Lala was alive, he was the head of the community,” says Deepak Rao, Bombay police historian. “Our relationship with him was good. He kept an eye on the community for us and would annually visit the Pathan branch of the Special Branch CID Bombay to renew the Residential Permits of the city’s Pathan community and mediate in any problems arising with the police. He was also a guarantor for their good behaviour.” This was necessary then as many Pathans were stateless, preferring Residential Permits (RPs) introduced by the British, that facilitated their movement across borders. According to the 1978 Annual Report of the Greater Bombay Police, there were 860 Pathans registered with the branch. Numbers have fallen since to about 400 today, and continue to decline.

Dock workers, guards, money-lenders

The Pathans began migrating to Bombay for work at the turn of the 19th century. Although Afghan traders were known to travel in caravans overland to the city, carrying carpets, dry fruit, saffron, and horses for sale, those who settled were largely labourers.

The towering build and strength of the average Pathan had them usually take up hard labour in Bombay’s dockyards and petroleum refineries at Trombay, or as security staff in textile mills and the bungalows of mill-owners. Marwari businessmen and other Sethias (wealthy native merchants) living in Malabar Hill preferred having them as watchmen: they were physically intimidating, but they were also loyal. “Another reason for this preference was that no other Pathan tribe was likely to come to maraud the place: that could lead to a tribal war in the North West Frontier Province,” says Rao.

It was from these beginnings that the Pathans are known to have entered into informal money-lending, becoming a resource to whom the others working alongside them in dockyards, mills, and refineries, could turn. “The Pathan money-lender does not want his original principal returned, he only wants his interest at the end of the month. His security is the fact that his debtor has a job,” says Rao.

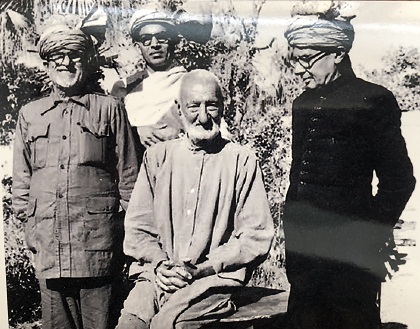

Now, Bombay’s mills have given way to plush commercial spaces – and the community is no longer as visible as before. The men’s trademark billowy shalwar-kurta, hennaed beard, long hair, and Pathan turbans have been replaced by a younger generation which favours western clothes and the latest hairstyles. They still inhabit Saat Rasta (Jacob Circle) in Central Mumbai and Fort, such as the area adjacent to Ballard Pier, with its parallel streets full of warehouses close to the docks. Groups of 20-30 Pathan men usually rent a big room here and hire a cook. A soupy mutton speciality, called Kadi Adhuke, is a staple. “It is a mutton curry that is eaten in communal fashion with a large roomali roti to mop up the gravy, each person sitting at the common thal (plate) with a bowl of the mutton curry,” says Bedar Khan. Pathan cuisine is not spicy, but the fare eaten in Mumbai has embraced the masalas and chillies used by other communities.

Though the Pathans have no masjid (mosque) of their own nor other institutions (like schools), they do have the Anjuman-i-Pukhtoon Trust to support their poor.

The Consulate General of Afghanistan in Bombay (established in 1915) too, has been another constant in the cultural life of the city’s Pathans. The community’s identity lies in its overseas network, which, in turn, has expanded this further with many Mumbai Pathans seeking work and business opportunities in West Asia and South East Asia. The community is smaller today than it was pre-Partition, but its contributions to the labour force, small businesses, overseas trade and culture, will always be a valued part of Bombay’s history.

Sifra Lentin is Bombay History Fellow, Gateway House.

This is the final in our two-part series on India-Afghanistan relations. Click here to read the second part.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] The 2016 Trilateral Agreement on Establishment of International Transport and Transit Corridor between India-Iran-Afghanistan makes it incumbent on India to build and operate Chabahar port. The lease is for a 10-year period that can be extended. Economic Times, “India takes over operations of part of Chabahar Port in Iran”, 7 jUne 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-takes-over-operations-of-part-of-chabahar-port-in-iran/articleshow/67424219.cms?from=mdr

[2] Ministry of External Affairs, “Embassy of India, Kabul, Bilateral Brief”, Government of India, December 2018, http://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Bilateral_Brief_on_Afghanistan_December_31_2018.pdf

[3] The International North–South Transport Corridor is a 7,200-km-long multi-mode network of ship, rail, and road route for moving freight between India, Iran, Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Russia, Central Asia and Europe. Bombay port is at the southern-most terminal of the INSTC. This will also synchronize with the Ashgabat Agreement also a multimodal transport agreement signed by India, Oman, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, for creating an international transport and transit corridor facilitating transportation of goods between Central Asia and the Persian Gulf.

[4] The inauguration of the Dedicated Air Cargo Corridor in June 2017 between Kabul-Delhi and Kandahar-Delhi has provided a fresh impetus to bilateral trade. Six months later, the Kabul-Mumbai Air Cargo Corridor was also inaugurated. The Air Corridor has ensured free movement of freight despite the barriers put in place due to the denial of transit by Pakistan.

[5] Trade data on India-Afghanistan trade for 2018-19 shared by Afghan trade commissioner Abdul Nafi Sarwari in Bombay. Interviewed on 6 November 2019.

[6] Afghanistan is well-known for its gemstones, particularly emeralds. These stones are imported into India (mostly Rajasthan) for value addition like cutting, polishing and setting, and then re-exported.

[7] Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPP) was formed in 2010 and comprises the old North West Frontier Province and the former Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA) to which many of the Pashtun Tribes of Mumbai belong. FATA was merged with KPP in 2018.

[8] According to Yakub Khan (interviewed on 7 November 2019), it was quite common for Pathan families in Peshawar to own ancestral lands just across the border in Afghanistan and/or own land that spread across the border.

[9] The Durand Line demarcation between the Kingdom of Afghanistan and British India came into being in 1893. Today, it is the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

[10] Caroe,Olaf, “The Pathans 550 B.C. – A.D. 1957″, London, MacMillan & Co. Ltd., 1958,p XV.

[11] Gorlinski, Virginia, “Pashtun”, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pashtun

[12] The tribal genealogies of the Afghans or Pathans were first written down by one Nematullah, a scribe at the court of the Mughal Emperor Jehangir, and completed about 1612 A.D, in a work titled Makhzan-i-Afghani. Very simply, all the tribes trace their ancestry to the eponymous hero of the Pathan’s, Qais alias Abdurrashid, who has three sons – Sarbanr, Bitan, Ghurghust. But there is a fourth, Karlanri, who is the putative ancestor of the hill tribes, he is linked to either Sarbanr or Ghurghust tribal trees (depending on the work being referred to). It is from these four ancestors that the tribal tables or shajras begin.

Caroe,Olaf, “The Pathans 550 B.C. – A.D. 1957″,London, MacMillan & Co. Ltd., 1958, pp 11-13.

[13] The interviewees for this article, referred to their Tribal Code as Pukhto, but the term Pashtunwali is used in academic works. See: Siddiqui, Abubakar, The Pashtuns: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan ( Gurgaon, Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd., 2014), p. 14.