China will be hosting the ninth BRICS summit in Xiamen, Fujian province in September this year. Much water has flowed under the bridge since November 2001, when economists at Goldman Sachs came up with the acronym. The countries in question saw in their unlikely group – the outcome of an American construct, ironically enough – the potential to form an alliance against the Anglo-Saxon dominance of the world. But it was a contrived one, politically: two of the members, Russia and China, had permanent seats in the UN Security Council, and the other two, India and Brazil, were aspiring members.[1]

Today, 16 years down the line, tangible conflicts and philosophical differences between the nations (such as, regulation of the Internet) do exist – and the multi-polar world that they seek remains unaccomplished. The U.S. withdrew leadership on issues such as climate change and free trade, but the U.S. economy mattered more for global economic growth than China’s, according to the 2015-16 annual report of the Bank for International Settlements. Even China’s economic rise has been due to the U.S.’s support. Even so, BRICS remains relevant, but to be able to dictate the global agenda, the leaders of these nations need to address the following financial issues at the forthcoming summit.

Addiction to debt

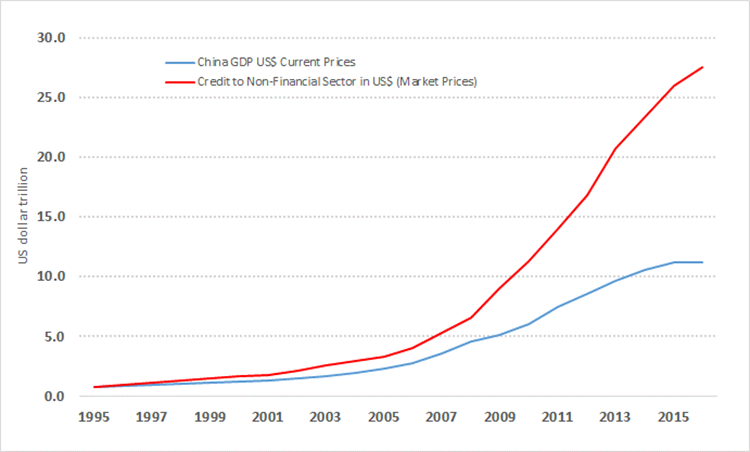

For BRICS to make sense as a political grouping, the nations have to break the paradigm of financial globalisation that has dominated western thinking and policy-making over the last three decades – and acknowledge that they too have made some of the West’s mistakes, such as the reliance on debt. China’s overall debt – non-financial debt, including the government’s – has ballooned since the new millennium, especially since the onset of the financial crisis of 2008, while its GDP has plateaued. What was supposed to be a crisis of the western nations saw China unleash a massive economic stimulus to bail its economy out, which added greatly to its debt stock. The problem with debt is that too much is a drag on economic growth, and China is fast approaching that point, if it is not already there.

Addiction to debt, therefore, has to be first moderated, then reversed. It will have short-term growth consequences, but it will make the economy healthier in the long term.

Regulating capital flows

Since the 1980s, free movement of capital has been added to free trade as part of the policy prescription for the developing world. However, not all capital is the same. Until recently, economists had ignored that distinction. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) came close to adopting capital account liberalisation as one of its missions in 1997. But, the Asian crisis stopped it. Lately, the Fund came around to accepting and even publishing research on evidence that capital flows can hurt economic and social stability in the developing world. For example, Davide Furceri and Prakash Loungani of the IMF[2] found that capital account liberalisation episodes were associated with a statistically significant and persistent increase in inequality. In particular, they found that, on average, capital account liberalisation reforms have typically increased the Gini coefficient by about 0.8% in the very short term (a year after the occurrence of the liberalisation reform) and by about 0.7- 2½% in the medium term (five years later). This outcome was due to the effect that capital account liberalisation had on the labour share of income, which declined after liberalisation. Therefore, it is essential for BRICS countries to stand up to pressure on capital account liberalisation.

Thirdly, closely related to the earlier point is the treatment of financial transactions. The U.S. and UK have resisted European proposals[3] to levy a tax on financial transactions that add no economic value. Such a tax would throw sand under the wheels of short-term trading which do not add any value to economies. Germany and France are in favour of it, but the U.S. and UK have resisted it because of the importance and clout that the financial sector holds for their economies. If BRICS nations lend their weight to the European proposal, it will gain traction. Financial markets will change from being casinos in disguise to being mechanisms for efficient long-term capital allocation.

Executive compensation

Evidence has emerged in America that listed companies invest far less in real assets than unlisted ones.[4] Public listing and executive compensation practices that reward executives for short-term stock price performance have combined to discourage companies from undertaking real investments. With the possible exception of China, other BRICS nations need more investments in physical assets for the next decade or two if their economic promise is to become reality. They should therefore institute regulations that keep executive compensation in check and executives accountable for the long-term performance of their companies. It is complex work that requires stakeholder consultations and BRICS nations need to address it speedily. There are signs in India, for example, that the ratio of executive pay to median worker pay in listed companies is higher than it is in the U.S.![5]

Addressing these issues will be proof that BRICS has an alternative to the western paradigm whereupon it can tackle related areas, such as regulating new financial products and the role of stock markets in society. This will also mark a fitting start to a second, more meaningful decade for the group.

Dr. V. Anantha-Nageswaran is Adjunct Senior Fellow, Geoeconomics Studies, at Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] South Africa became part of the group on 24 December 2010 and BRIC became BRICS.

[2] Davide Furceri and Prakash Loungani (2015): ‘Capital Account Liberalization and Inequality’, IMF Working Paper WP/15/243, November 2015, <https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2015/wp15243.pdf> (Accessed on 17 July 2017)

[3] See, for example, Weber Alexander, Jennen Birgit, “German Courting of London Banks May Falter on Tobin Tax Pledge”, Bloomberg, 24 January 2017 <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-23/eu-s-courting-of-london-banks-may-derail-5-year-tobin-tax-drive> (Accessed on 17 July 2017)

[4] Asker, John, Joan-Farre Mensa, and Alexander Ljungqvist (2014), “Corporate investment and stock market listing: A Puzzle?” Review of Financial Studies 28, no. 2 (February 2015), 342-390, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1603484 (Accessed July 17, 2017)

[5] “Pay Gap: Indian CEOs Earn Up to 1,200 Times More Than the Average Employee”, Business Standard News, <http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/pay-gap-indian-ceos-earn-up-to-1-200-times-more-than-the-average-employee-117072400066_1.html> (Accessed on 26 July 2017)