The recent United States-China trade deal, formally known as the ‘Economic and Trade Agreement between the United States of America and China’, signed on 15 January 2020, is a lengthy document. It is called a ‘trade agreement’, but it is not a trade agreement the way the term is used in trade parlance. It is a bilateral agreement, limited to a few product lines (mainly agriculture), select service sectors of American interest, and some topics tangentially related to trade, such as currency misalignment and forced technology transfer.

Importantly, this agreement was signed not when both nations enjoyed the best of economic or normal political relations; rather, it was born out of a trade war, which peaked during unilateral and retaliatory tariff skirmishes and was settled in a hurry as economic peace was badly needed.

President Trump could not have escalated the trade war over a few more months as his presidency had entered the election year and impeachment proceedings were drawing close. China too had limited options. World trade is not expanding any more. The American tariffs were too high, and the Chinese production chains were shifting to countries, such as Vietnam and Taiwan, to avert the long-term consequences of U.S.-China trade hostility.

What does the trade agreement cover? It recognises and attempts to provide market access to, and improved sanitary and phytosanitary protocols and standards for, certain identified agricultural, horticultural and biotechnology products, seafood and aquatic products. It provides limited market access to financial services and includes provisions that will prevent both parties from directing or supporting domestic firms or companies in acquiring technology in certain sectors that could cause distortion.

The agreement also includes some provisions on currency devaluation and dispute resolution.[1] At the same time, although not as part of the trade agreement, the U.S. has reduced the tariffs on $112 billion worth of Chinese goods from 15% to 7.5%[2] with effect from 14 February 2020.

Tariffs as swords in a trade war

The U.S.-China trade war appears to have been almost predetermined.[3] There was simmering discontent within the United States against China’s trade policies, especially the role of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and state-owned banking companies (SOCBs) in distorting production and supply decisions. The perceived lack of Intellectual Property (IP) protection and forced technology transfer in China were concerns which the American industry had repeatedly raised with the U.S. administration.

Trade tensions are normal; however, trade wars are rare. Trade wars reflect a total and brazen disregard for international trade agreements. The magnitude of trade affected by unilateral trade actions often reaches high proportions in a trade war. Trade wars also have a significant destabilising impact. Often, the impact is mainly on domestic consumers and user industries. More expensive inputs increase the cost of production.[4] Past experiences have shown the pernicious effects of tariff protection. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 ushered in beggar-thy-neighbour policies that eventually led to the Great Depression.[5]

The trade war essentially started in 2018 when the U.S. imposed global safeguard tariffs under Section 201 of the Trade Act, 1974. It escalated when the U.S. imposed Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium imports from various countries.[6] These actions were targeted at major exporting countries. Some countries, for instance, Korea, Argentina, Brazil and Australia, began a conversation with the U.S. and settled for a tariff rate quota (TRQ), or some form of grey measures, such as voluntary export commitments. The war slowly and gradually took its true form and turned mainly China-specific. The U.S. also initiated a Section 301 investigation against China in 2017 for its policies on Intellectual Property (IP), technology, and innovation.[7] China challenged the measures at the WTO towards the end of 2018.[8] Apparently, the two major reasons behind the trade war was the expanding trade deficit in U.S.-China trade and the concerns related to intellectual property enforcement in China.

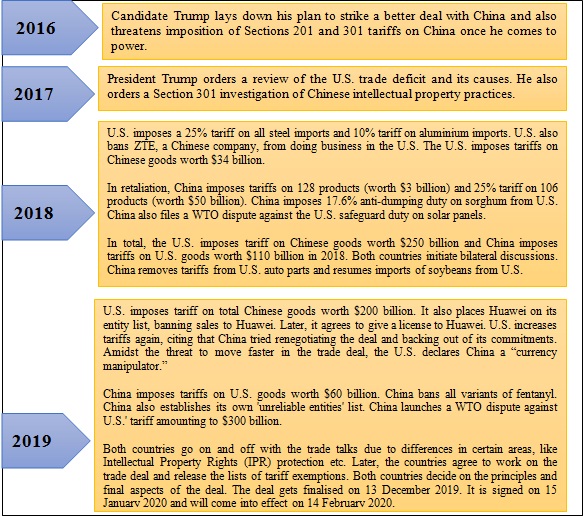

Storyline of U.S.-China trade war

Source: Centre for Trade and Investment Law (2020)

Trade deficit and the Agreement

Despite the retaliatory tariffs and other unilateral measures of the last two years, the U.S. trade deficit with China reached $353 billion by the end of 2019.[9] The U.S.-China Trade Agreement includes a clear commitment from China to increase U.S. imports by $200 billion from the 2017 baseline.[10] According to Gary Hufbauer of the Peterson Institute of International Economics (PIIE), it is almost a 55% increase of U.S. exports to China.[11] Questions have already been raised about how China will meet these commitments. Imports are often a reflection of consumer choice and preferences and governments typically do not play much of a role in meeting specific import targets from a particular country.

At least in the short run, China may have to enforce and oversee the managed trade to benefit from the exemption of retaliatory tariffs. In addition, some of the terms of the U.S-China Agreement could displace third country imports and raise the WTO’s concerns. The European Union has already hinted that it could possibly challenge the bilateral agreement at the WTO.

China’s market economy status in the WTO has been a thorn in the relationship between the two countries. Although China’s Accession Protocol, signed in December 2001, provided a market economy treatment at the end of 15 years, several WTO members still do not recognise China as a market economy for the purposes of anti-dumping investigations. Although China promptly challenged this measure in December 2016 – a day after the 15-year phaseout period ended – it seems to have resulted in an adverse verdict in a case filed against the European Union before a WTO panel. China later suspended the panel proceeding.[12]

Phase I of the Agreement does not deal with complex issues such as state-induced market distortions in China. This aspect may appear in Phase II of the Trade Agreement.[13] Interestingly, while the U.S. has been steadfastly striving to force China to embrace market economy principles, the forced commitment in the trade agreement to purchase U.S. goods and services indirectly requires China to retain its market interventionist policies.

Market access in agriculture products

Phase I of the Agreement seeks to provide market access to several U.S. agriculture goods in China. Importantly, various categories of animal feed, for example, distiller’s dried grains with solubles, feed additives, barley, almond meal pellets, timothy hay, etc., can claim access to a streamlined process for registration and licensing. Some of the obligations – for example, the timeline for completing a product review or renewing a license – are time-specific and mandate an action within a specific number of business days.

Although the trade potential in these agricultural products is unclear, it could rev up the sentiments of certain segments of farmers in the midwest or upper plains of the U.S. Almost 1 million people are employed in the animal and pet food industry in the U.S. and this is a sector of export importance for the Trump administration. The streamlined licensing procedure and the phytosanitary protocol could possibly open the Chinese livestock and animal feed markets, which have generally remained shut to international trade. Importantly, in 2020 alone, China is required to purchase $20 billion worth of agriculture products.

Currency manipulation and China’s holding of U.S. debt

China holds the second highest amount of U.S. debt after Japan. As of 2017, the U.S. owed China $1.17 trillion debt in the form of treasury bonds. While China has always maintained this level of debt to provide a cushion to its exporters against any sudden changes in currency exchange, China has also been pushing for the yuan to become a global currency. If China starts selling off the U.S. treasury bonds it holds, it could cause the value of the dollar to drop.[14] Doing so may also not be in China’s best interests as it would result in higher interest rates and lower consumption of Chinese goods in the U.S.

The U.S.-China Agreement contains a chapter on macroeconomic policies and exchange rate matters. It prohibits both the U.S. and China from competitive devaluation of currency and targeting exchange rates. Without any doubt, this chapter is aimed at disciplining China on its practice of currency devaluation. China was termed a ‘currency manipulator’ by the U.S. treasury department,[15] although in view of this agreement, it has been removed from this list.

Intellectual property issues between U.S. and China

The U.S. has previously accused China of IP ‘theft’, costing the U.S. as much as $600 billion per year.[16] China has consistently denied these allegations. On the other hand, its treatment of American semiconductor company, Micron, led the Trump administration to up the ante on China, including filing a WTO dispute in 2018.[17] The U.S. challenged, in particular, the Chinese laws which require forced technology transfer and inadequate recognition of the patent holder’s rights after the expiry of the technology transfer agreements.[18] China has been alleged to deny an opportunity to freely negotiate market-based terms in licensing and other technology contracts. The U.S.-China Agreement seeks to address this issue by prohibiting forced technology transfer and related violation of intellectual property.

China has come to a realisation about its over-dependence on the U.S. for technology. It has started boosting its own manufacturing of semiconductors and microchips. With the development of Chinese capacity, the exports of American companies are bound to slow down.[19] In an attempt to stem the slide of its dominance in the technology space, the U.S. government has considered removing Huawei from its entity list (list of the entities which are prohibited from trading with the U.S.). Huawei is a downstream user of almost 17% semiconductors and microchips exported from the U.S.[20]

The trade agreement pushes China to achieve a standard equivalent to the U.S. on the implementation of laws on various IP issues. The chapter on Intellectual Property Protection covers trade secrets, confidential business information, pharmaceutical-related IP, patents, piracy and counterfeiting on e-commerce platforms, manufacturing of counterfeit goods, bad faith trademarks, and judicial enforcement in IP cases.

Dispute resolution mechanism

When it comes to the enforcement of this agreement, the U.S. has focused on a proper evaluation and dispute resolution mechanism as part of the agreement. This focus originates from China’s history of reneging on its trade commitments. During the negotiations, the U.S. proposed a unilateral enforcement and evaluation method, where, if China deflects from the implementation of the agreement, the U.S. can impose measures and China cannot retaliate. China did not agree to this arrangement in May 2019. The present arrangement is in the form of an evaluation of the other party’s performance. It does not eliminate the possibility of retaliation. In fact, it provides a window for termination of the agreement on a unilateral basis.[21]

Conclusion

It appears fairly clear that the trade war was a deliberate effort on the part of the U.S. to seek market access to certain products and areas of export interest to the U.S., for example, trade in U.S. agriculture and biotechnology products and better enforcement of IPR in China. Yet, the Agreement will not be able to undo the consequences of the trade war, which has completely disrupted the international trading system, and especially, its leading institution, the WTO.

The WTO is too fragile to handle a crisis of this order. Besides, the value of this agreement remains in its enforcement. According to Raj Bhala, a professor at the University of Kansas and an authority on international trade law, the Agreement is “both surprising and disappointing”. On the one hand, it attempts to bring better trade disciplines, specifically in relation to China, but achieves this objective through ‘managed trade’, a concept antithetical to free trade.[22]

The Phase II agreement is still pending and that may only be negotiated after the presidential elections in the U.S. It could cover aspects like state-owned enterprises, Chinese subsidies, and issues related to digital trade and cybersecurity. At best, the Phase I Agreement only reflects a temporary truce, and that too, a precarious one.

James J. Nedumpara is Head and Professor, Centre for Trade and Investment Law, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi.

Manya Gupta is a Research Fellow, Centre for Trade and Investment Law, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2020 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] ‘Economic and Trade Agreement between the Government of United States of America and the Government of People’s Republic of China’, Government of United States, 15 January 2020,

[2] Federal Register,Wednesday, January 22, 2020, Vol. 85, No. 14

[3] Reuters, ‘Trump Targets China trade, says plans serious measures’, Reuters, 25 August 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-trump-china/trump-targets-china-trade-says-plans-serious-measures-idUSKCN10Z2JN, Accessed on 20 January 2019.

[4] Amadeo, Kimberly, ‘Trade wars and their effect on the economy and you’, The Balance, 7 December 2019,

https://www.thebalance.com/trade-wars-definition-how-it-affects-you-4159973.

[5] Madsen, Jakob B., ‘Trade Barriers and the Collapse of World Trade During the Great Depression.’, Southern Economic Journal, April 2001, Vol No. 67, No. 4, pp. 838-868 at 848-849. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1061574?origin=crossref&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

[6] Bown, Chad P. and Kolb, Melina, ‘US – China Trade War Timeline – An Up to date Guide’, Peterson Institute of International Economics, 24 January 2020. https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/documents/trump-trade-war-timeline.pdf.

[7] Morrison, Wayne M., ‘Enforcing U.S. Trade Laws: Section 301 and China, Congressional Research Service’, Congressional Research Office, updated 26 June 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10708.pdf.

[8] ‘Request for establishment of a Panel by China, United States – Tariff Measures on Certain Goods from China‘, WT/DS543/7, 7 December 2018, World Trade Organisation, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds543_e.htm.

[9] Amadeo, Kimberly, ‘US trade deficit with China and Why It’s so high‘, The Balance, 12 January 2020, https://www.thebalance.com/u-s-china-trade-deficit-causes-effects-and-solutions-3306277

[10] Article 6.2, Economic and Trade Agreement between the Government of United States of America and the Government of People’s Republic of China. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/phase%20one%20agreement/Economic_And_Trade_Agreement_Between_The_United_States_And_China_Text.pdf

[11] Hufbauer, Gary Claude ‘Managed Trade: Centerpiece of US – China phase one deal’, Peterson Institute of International Economics, 16 January 2020, https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/managed-trade-centerpiece-us-china-phase-one-deal.

[12] Communication from Panel, European Union – Measures related to price comparison methodologies, WT/DS516/13, World Trade Organisation, 17 June, 2019, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds516_e.htm

[13] Bown, Chad P., ‘Unappreciated hazards of the US – China phase one deal’, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 21 January, 2020, https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/unappreciated-hazards-us-china-phase-one-deal

[14] Sherman, Eric, ‘Rare Earths, Bonds and Permit Hell: 3 weapons China can use to escalate trade war‘, Fortune, 29 may 2019,

[15] U.S. Department of Treasury, ‘Treasury designates China as a currency manipulator’, Government of United States, 5 August 2019,

https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm751, Accessed on 21 January, 2020,

[16] Goldstein, Paul, ‘Intellectual Property and China: Is China stealing American IP?’, Stanford Law School, 10 April 2018,

https://law.stanford.edu/2018/04/10/intellectual-property-china-china-stealing-american-ip/

[17] Office of the United States Representative, ‘Update concerning China’s Acts, policies and practices related to technology transfer, intellectual property and innovation’,Government of United States, 20 November, 2018.

https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/enforcement/301Investigations/301%20Report%20Update.pdf

[18] Request for consultations by the United States, ‘China – Certain measures concerning the protection of intellectual property rights, WT/DS542/1 IP/D/38′, World Trade Organisation, 26 March 2018.

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds542_e.htm

[19] Swanson, Ana & Kang, Cecelia, ‘Trump’s China Deal creates collateral damage for tech firms’, The New York Times, 20 January 2020,

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/20/business/economy/trump-us-china-deal-micron-trade-war.html

[20] Tayal, Puja, ‘Micron and the China trade war uncertainty’, Market Realist, 23 September 2019, https://marketrealist.com/2019/09/micron-and-the-china-trade-war-uncertainty/

[21] Office of the United States Trade Representative, Article 7.4, ‘Economic and Trade Agreement between the Government of United States of America and the Government of People’s Republic of China’, Government of United States, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/phase%20one%20agreement/Economic_And_Trade_Agreement_Between_The_United_States_And_China_Text.pdf

[22] Krings, Mike, ‘US-China Agreement ‘surprising, disappointing,’ only addresses some security concerns KU Trade expert says’, The University of Kansas, 15 January, 2020, https://news.ku.edu/2020/01/15/us-china-agreement-surprising-disappointing-only-addresses-some-security-concerns-ku, Accessed 20 January 2020