The event was moderated by Gateway House Mumbai History Fellow Sifra Lentin. The panel comprised Calcutta-based novelist Amit Chaudhuri, documentary film-maker Rafeeq Elias, and conservation architect Kamalika Bose.

Bombay (Mumbai) is well known as India’s international face, but that Calcutta (Kolkata) was the capital of British India until 1911 is almost forgotten. As underscored by the recent panel discussion on Calcutta co-hosted by Gateway House-Avid Learning for the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival, Calcutta was, and is much more than its tumultuous political past and present. It is a cosmopolitan multicultural city.

The panel discussion’s evocative title “Tea & Tangra” connected Calcutta’s past with Kolkata’s present as tea is the eponymous symbol of the city’s exports—through the tea auction houses—dating back to the eighteenth century. Tangra (or New China Town) is a precinct of the city still home to the largest community of Indian Chinese. The Chinese presence, too, dates back to the eighteenth century.

Cosmopolitan Calcutta

Amit Chaudhuri began the discussion by pointing out that his first non-fiction work, Calcutta: Two Years in the City (2011), is, among other things, a keen observation of the bhadralok (the middle-class Bengali) and his idiosyncrasies. It is from this perspective that cosmopolitan precincts like Park Street with its fairy-tale lights and New Year’s Eve celebrations, or the anglophone Bengal Club, are framed alongside what might seem their opposite—the sweet shops, art deco cinema houses that screened Bengali films, and the Durga Puja festival established in the nineteenth century under the patronage of landlords. It became a secular obsession with the bhadralok in the twentieth century, and now, like Christmas, become substantially blue collar.

The most cosmopolitan Bengalis were not the so-called ingabanga (English Bengalis) in their suits, speaking perfect English and using cutlery, but the dhoti-clad bhadralok. An educated, middle-class Bengali—the “small man” of modernity—he spoke English as a second language, but was as conversant with Rilke and Godard as with Kalidasa and Indian classical music.

Calcutta’s ethnic precincts

Calcutta was home to not just vibrant Chinese and Anglo-Indian communities, but older European and Eurasian communities who had emigrated from the Dutch colony Chinsurah, the Danish colony Serampore, and the French colony of Chandernagore, in Bengal, downriver (The Hooghly) to Calcutta.

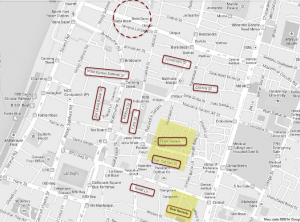

An interesting observation made by Kamalika was on the difference between the built heritage of Calcutta and Bombay. The latter has a largely white town within the Fort walls and a black town of native quarters outside, to the north, while the former also had a ‘grey’ town sandwiched between white south and black north. And it was in this grey midsection that predominantly foreign immigrant settlements came up—ethnic street names Ezra, Pollock, Sun Yat Sen, Grant, Old China Bazaar, and Armenian Street, are all milestones for communities that flourished from the eighteenth to mid-twentieth century in Calcutta.

- Ethnic diversity: reinforced through nomenclature of Streets. Image courtesy: Kamalika Bose

Today, the only two ‘viable’ foreign immigrant communities are the Chinese (approximately 2,000) and the Anglo-Indian communities. In fact, The Cha Project (an ongoing heritage restoration project) aims at reviving the living heritage of Tangra by creating more jobs for the resident Chinese, making it a tourist destination like Singapore and New York’s China towns. In contrast, the Indian Chinese presence in Mumbai’s old China Town on Nawab Tank Road outside Mazagaon Docks, and its newer Chinese precinct in Shuklaji Street (Kamathipura), is minimal.

Documentary maker Rafeeq Elias’s award-winning film for BBC on the Indian Chinese in Calcutta—the Legend of Fat Mama—explores the trauma the community underwent in the outbreak of the 1962 Indo-China War. The internment of Indian Chinese communities of Calcutta, Bombay, and elsewhere, in Deoli (Rajasthan), was the main reason for their large-scale immigration to Canada and Australia.

The narrative of the other indigenous foreign communities, like the Baghdadi Jews, Armenians, and Greeks—all trading communities—is different, with these communities having dwindled to unsustainable levels in Calcutta: a local Baghdadi Jewish community of only 30 (approximately 150 in Mumbai); Armenian community of 200, and an unknown number of Greeks. However, all these trading communities left behind a rich legacy of monuments and institutions: three magnificent Jewish synagogues, a still standing Greek Orthodox Church founded in 1925, and the second-oldest Armenian Church in India, the Holy Church of Nazareth (1724).

- Armenians of Kolkata. Image courtesy: Kamalika Bose

- Magen David Synagogue (1884). Image courtesy: Kamalika Bose.

What is intriguing is the way in which the living legacies of these minuscule communities make their reappearance. Little over five years ago, the Armenian College Rugby Team from Calcutta played a tournament at the Bombay Gymkhana in Mumbai, making one wonder how there are so many young Armenians rugby players in the country.

Apparently, there is yearly migration of Armenian students from all over the world to study at the Armenian College & Philanthropic Academy founded in 1821 in Calcutta originally endowed by wealthy nineteenth-century Armenian traders. It is this yearly infusion of young people that keeps the local Armenian community going.

In Mumbai, on the other hand, vestiges of its once flourishing Armenian community are hard to come by. Not only is the community virtually non-existent, but its historic St. Peter’s’ Armenian Church, which once fronted Medows Street in the Fort area and rebuilt in 1957, stands hidden behind Ararat building, its doors mostly locked, and its fate reflective of the flourishing community it once served.

Sifra Lentin is the Mumbai History Fellow at Gateway House.

This blog was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.

© Copyright 2016 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.