“With its skilled human resources and technical talent, India can emerge as a global platform for defence hardware manufacture and software production. BJP will strengthen the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO); encourage private sector participation and investment, including FDI in selected defence industries,” read the election manifesto of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) released in April 2014.[1] Two years into their administration, the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance government has kept its promise in that it has expeditiously cleared long-pending weapons acquisitions, accompanied by an intense push for local production of military hardware.

This push is important for three reasons: a) India is in the midst of an ambitious military modernisation programme, b) the regional security environment around the country remains perilous, and c) the Modi government has sought to undergird India’s expanded international profile on economic diplomacy of which ‘business of defence’ is a critical part. Given its heavy reliance on imports for critical military hardware, it will certainly take some time for India to shed its position of being one of the world’s largest arms importers, but the political willingness to reduce import dependence by creating a domestic defence industrial base, is apparent.

The first step the Modi government took when it came to Delhi in May 2014 was to regularly hold the meetings of the Defence Acquisition Council (DAC) – a body set up in 2001 but largely unheard outside the Ministry of Defence (MoD) circles– practically on a monthly basis, to clear long pending hardware demands of the military. The DAC consists of the Defence Minister, along with the three service chiefs and the senior MoD officials. A list of important proposals cleared by the DAC since May 2014 is placed in Table 1.

Table 1- Important military hardware proposals cleared by the DAC since May 2014

| Equipment | Vendor(s) | Approximate cost |

| Seven P17A stealth frigates | Mazgaon Docks; Garden Reach Shipbuilders and Engineers | Rs. 50,000 crores |

| Six P75I submarines | N.A. | Rs. 60,000 crores |

| 15 Chinook CH-47 heavy-lift transport helicopters | Boeing | Rs. 7000 crores |

| 22 AH-64E Apache attack helicopters | Boeing | Rs. 8000 crores |

| Seahawk Multi-role S70-B helicopters | United Technologies | Rs. 1,800 crores |

| Four Landing Platform Docks | Hindustan Shipyard Limited and a private shipyard* | Rs. 25,000 crores |

| Avro aircraft replacement programme | Tata-Airbus* | Rs 23,000 crores |

| Light utility helicopters | Rostec-Hindustan Aeronautics Limited | Rs. 6,000 crores |

* contract pending

Source: Gateway House research

An important part of this was keeping up with imports to meet the military’s immediate operational requirements, with particular emphasis on government-to- government agreements. For medium and longer term requirements, New Delhi has been promoting local defence production.

The second step, along with the clearances of proposals for the immediate purchase of hardware, was the much-needed policy changes, like:

- Reviewing the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) policy for the defence sector and raising the cap for foreign investment to 49% from 26%[2];

- Updating the ‘Defence Products List’ by de-licensing non-lethal and dual-use items[3];

- Giving additional industrial licenses for defence production to a growing number of private companies, taking the total number to more than 150 companies[4] from 127 in 2010[5];

- The most important of these steps was the launch of the ‘Make in India’ initiative for reviving the manufacturing sector, including local defence production. Again, the government placed a special emphasis on the participation of the private sector, which for a long time has played a second fiddle to the defence public sector units (DPSUs) in defence production. They were encouraged to participate in three big ticket acquisitions for the military- the P75I submarines and Landing Platform Docks (to be split equally between a DPSU and a private shipyard) projects for the Indian Navy and the Avro transport aircraft replacement project of the Indian Air Force.

The third step came a year later in May 2015, when the government set up an experts committee under the chairmanship of Dhirendra Singh- Committee of Experts for Amendments to Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) 2013, to align ‘Make in India’ with defence procurement. Based on the committee’s report[6], in March 2016 the new DPP-2016 was announced. The new policy seeks to prioritise buying locally-developed military hardware for the three defence services through the introduction of a new category called IDDM (Indigenously Designed, Developed and Manufactured).[7] Those Indian defence companies, which can locally design and develop the required equipment, will be preferred by the MoD when it buys new weapons for the military.

As expected there is a pushback from DPSUs for the enhanced role of the private sector. This was evident in two cases: one was the acquisition of light utility helicopters where India signed a deal with the Rostech Corporation of Russia to assemble the Kamov-226T helicopters in India with an Indian partner. After intense lobbying, the project which was expected to be awarded to a private aerospace company ultimately went to the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited.[8] The second case – the proposal to build four amphibious vessels- was cleared before May 2014 and had been reserved exclusively for private shipyards. However, the DPSU- Cochin Shipyard Limited- made repeated but eventually futile attempts to break into project.[9]

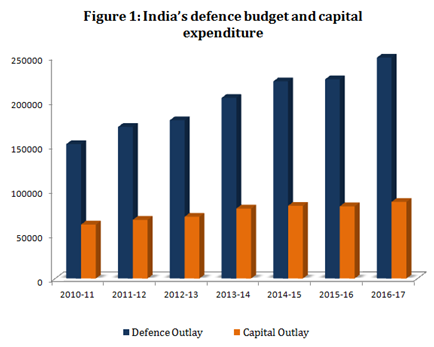

These positive steps notwithstanding, New Delhi has been unable to find its way around the protracted defence procurement-related decision-making tangles within the MoD and other ministries. This is evident by the fact that one and half years after announcing big ticket weapons acquisitions- the Acceptance of Necessity (the first step in the process of a military contract) by the MoD, final contracts are not yet in sight for those acquisitions, causing much consternation within India’s private sector. For instance, in the Avro aircraft replacement programme, despite the DAC approving the Tata-Airbus consortium’s bid for the project in May 2015, even the preliminary field trials of the replacement aircraft has not yet begun.[10] Ditto with the strategically important arms deals with Japan (ShinMaywa US-2 amphibious aircraft) and France (Rafale fighter jet) which are still mired in negotiations. Also, the services have expressed concerns over the capital expenditure budget (see Figure 1), which when adjusted to current levels of inflation, is simply not sufficient for purchasing state-of-the-art military hardware.

Rs. in thousand crores; Figures for 2016-17 are budgetary estimates

Rs. in thousand crores; Figures for 2016-17 are budgetary estimates

Source: Ministry of Finance[11] and Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses[12]

India is expected to spend $130 billion over the next eight years on buying new weapons.[13] It is imperative that the government leverage the experience and infrastructure of the DPSUs along with the manufacturing and managerial capabilities of the private sector.[14] This, combined with a focus on defence research and development (R&D) will ultimately help India realise the true potential of the IDDM category as envisaged in the DPP-2016. The Modi government has taken the initial steps towards this by identifying a few projects for co-development and co-production with the United States[15] such as Mobile Electric Hybrid Power Sources and protective body suit against chemical and biological warfare.[16]

Time now to create the ‘Defence Technology Development Fund’ first proposed in 2005 by the Kelkar Committee.[17] That proposal was never implemented but in order to transition from ‘Make in India’ to ‘Made for India’, the private sector will need to be encouraged, with the government’s backing. Globally too, there is a trend towards greater involvement of the private sector-led defence R&D. Indian private sector companies such as L&T, Tata Power Strategic Engineering Division and Rolta have been successfully involved in some of the current R&D projects and this process needs to be institutionalised. It must be accompanied by clearly defined technological priorities, understanding global technological trends and identifying critical technologies, especially those that may be denied to India as part of the many technology denial regimes.[18] Only then can India’s arms import vulnerability be overcome, a robust domestic defence industrial base be built, and the next three years of the Modi government be remembered for creating strong defences for India.

Sameer Patil is Fellow, National Security, Ethnic Conflict and Terrorism, at Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2016 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Bharatiya Janata Party, “Ek Bharat, Shreshtha Bharat: Election Manifesto 2014”, 7 April 2014, <http://www.bjp.org/images/pdf_2014/full_manifesto_english_07.04.2014.pdf>

[2] Lok Sabha, Government of India, Statement referred to in reply to parts (a) to (e) of Lok Sabha Starred Question no. 198 for answer on 5.12.2014, 5 December 2014, <http://164.100.47.132/Annexture_New/lsq16/3/as198.htm>

[3] Lok Sabha, Government of India, Statement referred to in reply to parts (a) to (e) of Lok Sabha Starred Question no. 198 for answer on 5.12.2014, 5 December 2014, <http://164.100.47.132/Annexture_New/lsq16/3/as198.htm>

[4] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, “Committee of Experts for Amendments to DPP 2013, including Formulation of Policy Framework”, July 2015, <http://www.mod.nic.in/writereaddata/Reportddp.pdf>, p. 29.

[5] Lok Sabha, Government of India, Starred Question no. 256, 15 March 2010, <http://164.100.47.192/Loksabha/Questions/QResult15.aspx?qref=84268&lsno=15>

[6] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, “Committee of Experts for Amendments to DPP 2013, including Formulation of Policy Framework”, July 2015, <http://www.mod.nic.in/writereaddata/Reportddp.pdf>

[7] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, “Defence Procurement Procedure-2016”, <http://www.mod.nic.in/writereaddata/Background.pdf>

[8] Pubby, Manu, “India and Russia to jointly manufacture Kamov 226 helicopter under ‘Make In India’”, The Economic Times, 24 December 2015, <http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-and-russia-to-jointly-manufacture-kamov-226-helicopter-under-make-in-india/articleshow/50316231.cms>

[9] Press Trust of India, “Rs 25,000 cr Navy tender only for private sector: Defence Ministry”, Business Standard, 14 September 2014, <http://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/rs-25-000-cr-navy-tender-only-for-pvt-sector-def-ministry-114091400397_1.html>

[10] Pandit, Rajat, “Tata-Airbus project yet to take off from drawing board”, The Times of India, 18 February 2016, <http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Tata-Airbus-project-yet-to-take-off-from-drawing-board/articleshow/51032972.cms>

[11] Ministry of Finance, Government of India, Union Budget 2016-17, 29 February 2016, <http://www.unionbudget.nic.in/vol2.asp?pageid=2>

[12] Behera, Laxman K., “All About Pay and Perks: India’s Defence Budget 2016-17”, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses Issue Brief, 3 March 2016, <http://www.idsa.in/issuebrief/pay-and-perks-india-defence-budget-2016-17_lkbehera_030315>

[13] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, Make in India-Defence Sector, 28 January 2015, <http://pib.nic.in/newsite/mbErel.aspx?relid=114990>

[14] Patil, Sameer, “The business of defence: role of India’s private sector”, Gateway House Policy Perspective No. 8, Gateway House, 12 May 2015, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Sameer-Patil_Policy-Perspective_May12.pdf>, p. 8.

[15] Department of Defense, Government of the United States of America, “Framework for the U.S.-India Defense Relationship”, 3 June 2015, <http://archive.defense.gov/pubs/2015-Defense-Framework.pdf>

[16] Patil, Sameer, “Carter in India: a foundational visit”, Gateway House, 14 April 2016, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/carter-in-india-a-foundational-visit/>

[17] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Kelkar Committee submits report on defence acquisition, 5 April 2005, <http://pib.nic.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=8386 >

[18] Patil, Sameer, “The business of defence: role of India’s private sector”, Gateway House Policy Perspective No. 8, Gateway House, 12 May 2015, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Sameer-Patil_Policy-Perspective_May12.pdf>, p. 10.