Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is currently on a two-day trip to India. It’s a good time for the visit. The India-Japan bilateral today is at its most exalted level of trust and shared goals, evident from the “special strategic and global partnership” they share. It is a relationship that has extended into a multilateral forum like the QUAD, and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, whose main aim is to secure a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ against more belligerent powers like China in the region.

Look back a few centuries, and a historian will find that Japan’s Edo Period (1603-1867) cartography provides an insight into contemporary India-Japan relations. This was the focus of a recent lecture on cartography in Edo Print culture, part of an international conference on ‘Discovering India-Japan civilizational ties and South East Asian Connectivities’ in New Delhi.[1]

The Edo Period of Japan also known as the Tokugawa Shogunate, witnessed the national seclusion of Japan to outside influences for over 200 years (1633-1854), with the exception of the Chinese and the Dutch. It also saw the country’s reopening in the Shogunate’s twilight years, when confronted by European powers clamouring for access to its ports and markets. Because of Japan’s relative isolation, lack of direct contact with the Subcontinent, and the vast influence of its numerous Buddhist sects, the maps of the Edo period were informed by medieval Japanese maps. These adopted the Buddhist worldview that placed India at the center of the human world. This habitable realm was confined to just one continent known as Jambudvipa, which comprised India (Tenjiku[2]), China (Shintan), and Japan (Honcho or “our country”). [3]

The Buddhist spiritual worldview was based on classical Buddhist texts like the Abidharmakosa, and the Chinese monk Hsuan-Tsang’s records of his travels to the Subcontinent in the 8th century. When new knowledge of India like new ruling dynasties or kingdoms filtered into Japan, new box captions were added to these maps.

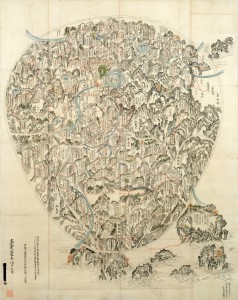

The five regions that comprised Tenjiku are not the Indian subcontinent of modern geography. Taken together the five were a largely imaginary realm encapsulated in a bulky ovoid (see Image 1) that does not resemble the peninsular shape of the Subcontinent. Japan had no first-hand knowledge of the India and its surroundings. The best-known early interaction is that of the Indian Buddhist monk Boddhisena who traveled to Japan via China at the invitation of the Japanese emperor. Boddhisena was the chief officiant in 752 CE, to perform the eye-opening ceremony of the giant bronze Buddha in the Todaiji Temple in the capital Nara. But this singular event does not point to regular contact between the two. It was always through Imperial China and the Korean peninsula that Indian influences made their way to Japan.

The oldest map of the continent of Jambudvipa in existence is a large hanging scroll titled Go Tenjiku zu (Map of the Five Regions of Tenjiku) in the Horyuji Temple near Nara.[4] It was made in 1364 by the Buddhist priest Genjiko Jukai. This map marks in red the route taken by the legendary Chinese traveler and monk Hsuan-Tsang[5] .[6]

It is significant that the ovoid landmass of India fills these maps almost entirely, emphasizing India’s importance in the Japanese-Buddhist imagination. China occupies a small area in the northeast, and Japan is a large archipelago further away from China. The placement of the three regions shows India as a distant realm beyond the Chinese cultural sphere and as a sacred site that was yearned for. This is revelatory: at the time, it was akin to a pushback by the then not-so-powerful Japan to the influential Confucian view of China being the center of the world.

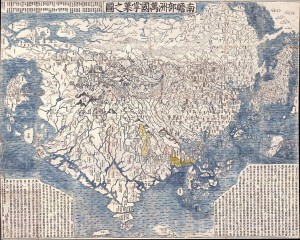

It is a narrative that continued into the Edo print culture from the 17th to early 19th centuries, which in turn popularized this imagery of India for the Japanese layman. According to Prof. D. Max Moerman, a specialist in Edo print culture, medieval Tenjiku (India) entered the public realm with scholar-priest Soshun Hotan’s[7] 1710 wood-cut map with hand colouring, which shows Tenjiku with its myriad kingdoms like the Mughal empire, held like a “fruit” in the hand of Japan and China. The Buddhist cosmological representation[8] of India had not changed but the representation of China was updated by a Chinese “General Map of the Ming and all the surrounding countries” (1663)[9]. Hotan’s map was revolutionary as it was the first printed ‘oriental’ world map that attempted to fuse Western cartographical information reaching Japan with the traditional Buddhist view, a prototype for maps till the mid-19th century.

This vision of an idealized India as the center of the habitable world in keeping with Buddhist cosmology and geography, was perpetuated over a period of 500 years. Japan’s self-imposed seclusion during the Edo Period[10], when only licensed Japanese merchants conducted overseas trade and only the Chinese and Dutch were allowed to sail into designated Japanese ports, reinforced that idea of India into the mid-19th century. [11] It overlapped with the period when modern European maps based on physical explorations were slowly making their way into the country, first brought by Jesuit missionaries and then Dutch traders.

After the signing of the 1858 Harris Treaty between the United States and Japan, Japan’s isolation ended by opening its ports to international trade and contact with the outside world, and India. It resulted in a diminution of Buddhism in Japan, a rise in Japanese nationalism, and a more scientific approach being adopted by the restored Meiji Emperor to accelerate industrialization in his country, all of which contributed to the erosion of an idealized Tenjiku.

India, however, was never forgotten. During the country’s freedom struggle, the founder of the Japan Buddha Order (Nippozan Myohoji), Fujii Guruji, traveled to India in 1931 to aid its freedom struggle. This was in the belief that if Buddha Dharma did not return to its holy land via Japan, India would never be free. It was in Mumbai that this Japanese order chose to build its Temple (Japan’s Buddhist Trail in Bombay).

Though it is well-known that Buddhism is an important soft power in India-Japan relations today, the geopolitical context of Buddhist spiritual maps that wielded such a profound influence first on Japan’s Buddhist clergy and then its laity, reveals a world view that echoes the present.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

©Copyright 2023 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] The lecture titled “Representing India in Edo Print Culture” was delivered by Prof. D. Max Moerman at the International Conference “Discovering India-Japan Civilizational Ties and Southeast Asia Connectivities” hosted by Kizuna India-Japan Study Forum (powered by MOSAI) and India International Centre (New Delhi) on 10-11 February 2023.

[2] The name Tenjiku literally translates to Ten=Heaven and Jiku=Bamboo.

[3] There is no reference to Japan in ancient Buddhist texts, so the Japanese made an inference about their location as being northeast of China.

[4] Rambelli, Fabio, ‘The Idea of India (Tenjiku) in Pre-Modern Japan’, Chapter 12 in Sen Tansen (Ed), Buddhism across Asia: networks of material, intellectual and cultural exchange, (Singapore, ISEAS, 2014), p. 265.

[5] The Go Tenjiku zu is quite large, which led Japanese studies experts in the field of Buddhism and East Asian art, to speculate that they were in fact used for eidetic meditation. Buddhist monks used it as a visual aid to enter a deep meditative state where they believed they could experience the key events in the life of the Sakyamuni Buddha

[6] This was remarked on in Prof. D. Max Moerman’s lecture (see footnote 1), and also in Rambelli, Fabio, ‘The Idea of India (Tenjiku) in Pre-Modern Japan’ , Chapter 12 in Sen Tansen (Ed), Buddhism across Asia: networks of material, intellectual and cultural exchange (Singapore, ISEAS, 2014), p. 265. This hypothesis is based on Monk Zenjo writing in the margins of his 1364 map of Tenjiku that “ for the future prosperity of Buddhism, I copied this map rubbing my old eyes and dreaming of travelling to India.”

[7] Soshun Hotan (1654-1728) is famous as the founder of the Kegonji Temple in Kyoto.

[8] This Map shows the two Americas, Europe, and Turkey but omits the continent of Africa. The largest part of the map depicts the continent of Jambu-Dvipa, at the center of which is the sacred Lake of Anavatapta (Lake Manasarovar in the Himalayas) in Tenjiku, from which the 4 rivers Ganges, Oxus, Indus, and Tarim flow. This was based on the Japanese version of Hsuan-Tsang’s Chinese narrative, the Si-yu-ki that printed as late as 1653.

[9] This map of China was informed by Jesuit cartographers Matteo Ricci and Julia Aleri. It was first reprinted in Japan in 1706.

[10] The Edo period is also known as the Tokugawa Shogunate era, a time when it was ruled by feudal warlords,

[11] Hotan’s map was a prototype for other maps during this period. Also significant was the cartographer’s choice to show Europe as a cluster of islands in the northwestern margins, South America likewise, and North America as unnamed and pushed into the map’s northeastern boundary. This is significant because in the early 18th century the Portuguese Jesuits, European and American traders, and diplomats, were already interacting with the Japanese.