One approach to understanding Bombay’s overseas spheres of influence is to trace the history of its multicultural migrant trading communities and their overseas networks. Some of these diasporas were created before Bombay, the trading city existed but were transposed here when these communities made the city their spiritual and community headquarters.

The city became attractive to these internal migrants from the 18th century onwards because of its relative security, trade, commercial and connectivity advantages on the west coast – both overseas and inland. This spurred Indian trading communities to shift to the city. The English East India Company (EEIC) government actively encouraged these enterprising communities, largely those concentrated in Surat and its vicinity during the 17th and 18th centuries, to Bombay, by offering religious freedom and tax breaks. Large influxes occur at inflexion points like droughts, famines, epidemics and political upheavals in their home cities, towns or villages.

Not only did these communities – Bhatia, Jain, Marwari, Bohra, Khoja, Memon, Parsi and later Partition refugees, like Sindhi and Sikh – build entire community ecosystems in the city (places of worship, community halls, schools, colleges, hospitals, orphanages, housing) but also individuals who succeeded enormously contributed to the building of the city itself. The sheer scale of merchant philanthropy in Bombay makes it unique among Indian cities, especially when compared to the British Indian capital cities of Calcutta (1772–1911) and later New Delhi. Merchants donated to the building of the city’s key institutions like hospitals, universities, research and educational; infrastructure like the Mahim Causeway (donated by Lady Avabai Jeejeebhoy, wife of Bombay’s merchant prince Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy), and even landmarks – like the ceremonial arch of Gateway of India at Apollo Bunder.

Far more pertinent are the overseas community networks they spawned but nurtured from the city. Though these networks were driven by business and sustained by profits, a diaspora presence in- creased when manpower from the community pool, brides and even entrepreneurs actively circulated between the city and its diasporic nodes. The more profitable and promising a region was, the more resources – goods, credit and manpower – would be invested in it.

What is important is that 200 years later these networks still exist between the city and West Asia, East Africa and Hong Kong, while connections between former strongholds like mainland China and Japan are diminished in contrast to their robust historic presence. It is the western arc of the Subcontinent’s coasting trade with the Arabian Sea littoral comprising the Persian Gulf (Oman, Iran), West Asia and East Africa that is home to the earliest presence of trading communities from India’s west coast. One of the oldest, strongest and culturally richest networks still remains the Bombay–Oman–East Africa overseas connections

Slaves, ivory and cloves: the East Africa trade

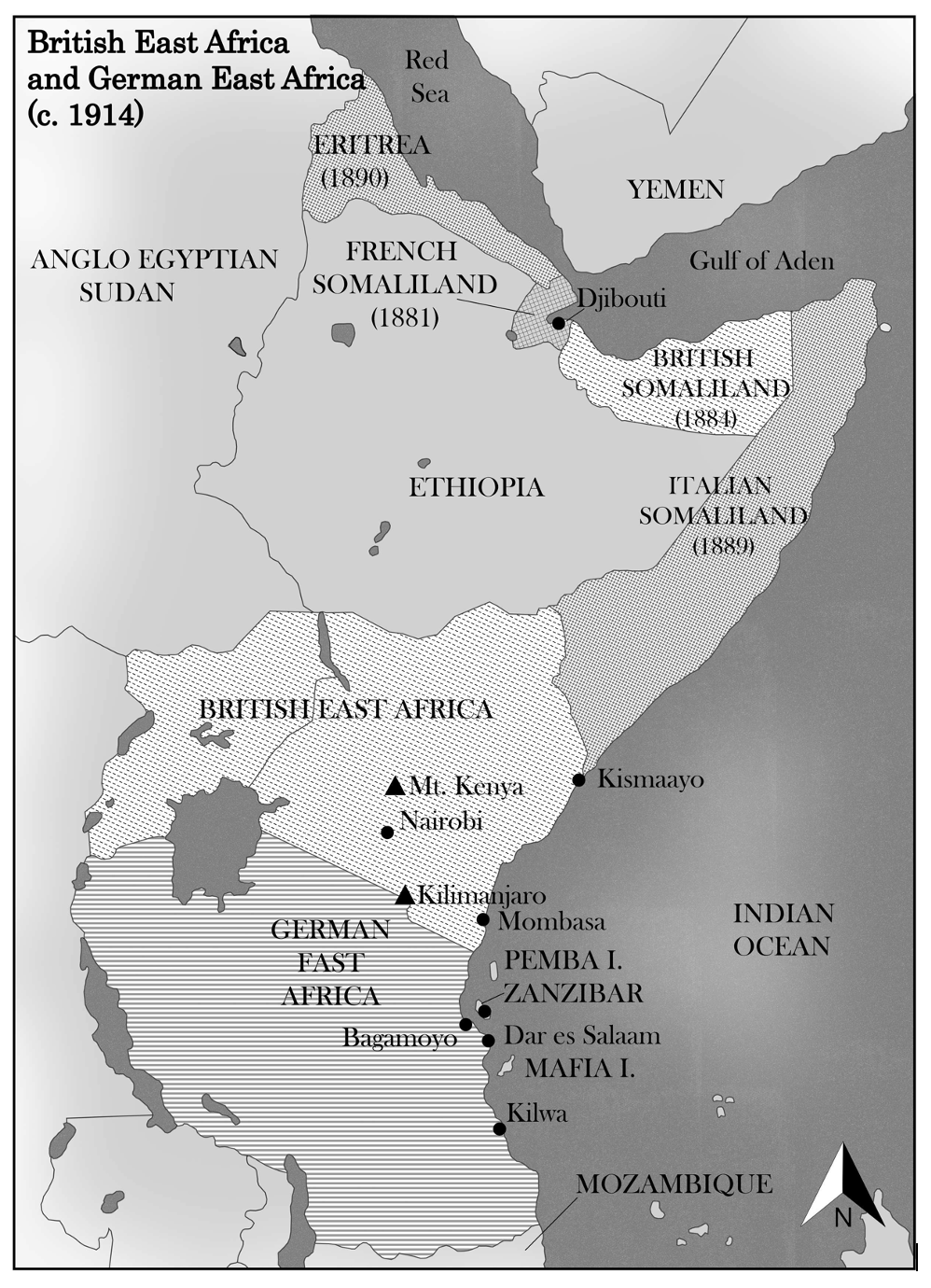

Oman takes centre stage in the links between Bombay and East Africa as an historic axis of trade between the two regions. Its centrality began with Omani hegemony since the 17th century over most of the island states off the East African coast and its control of the mainland Mrima coast opposite Zanzibar Island (the Omani capital in Africa sometime from 1832–1840), which facilitated trade not just with Bombay but also with Britain, America, France, the German-speaking Hanseatic states and later Germany.

The Omani Arabs then under the leadership of the founder of the Ya’arubi dynasty Imam Sultan ibn Saif rose in revolt and threw the Portuguese out of Muscat in 1650. Soon after, in 1652, the Sultan sent a small fleet to raid the islands of Pate and Zanzibar. This began the Omani intervention in East Africa. Pertinently, the Omanis were the first maritime power to break the 16th-century Portuguese stranglehold over the Indian Ocean trade routes, partly reclaiming Arab control over trade and shipping in this region.

By 1658, the Omanis had acquired Zanzibar, and in 1698, they wrested Fort Jesus in Mombasa from the Portuguese. Omani dominion, from the mid-18th century, now under the current Busaidi dynasty, continued over this region (with the exception of Portuguese-ruled Mozambique and its surroundings) till the late 19th century before they yielded to Great Britain. However, their control over this region was more akin to a soft hegemony to facilitate trade rather than territorial acquisitions with clearly defined borders (Roland and Mathew 1963).

Source: From the collection of Sifra Lentin.

Broadly, the Omani-controlled choke points in the Arabian Sea were Zanzibar, Mombasa and Muscat, all watering stations and important trade marts before the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. This hegemony extended to the port of Gwadar (now in Pakistan), controlled by them till 1958, which gave them victualling home ports for their dhows on the route to the subcontinent (Kaplan 2011).

Making the most of Omani control in the maritime sphere by early 17th century, a considerable community of Hindu merchants (largely Bhatia from Rajasthan and Gujarat) settled in Muscat, Hormuz, Aden and Zanzibar. They were joined by Muslim Khoja, Bohra and Memon communities from the subcontinent’s west coast. It was from here that a few ventured to trade with Lamu, Mombasa, Bagamoyo, Kilwa, Lindi, Zanzibar and Pemba, in the wake of these ports and regions coming under Omani control or political influence.

Portuguese-controlled ports in the Persian Gulf and East Africa that later came under Omani rule

In these early years, Indian merchants traded in Muscat dates, Arabian and Persian horses, gold and slaves from Sofala (on the East African coast), ivory from East Africa, Indian piece goods (cotton cloth), food grains from India and Chinese porcelain and silks. It was largely an intra-Asian (coastal) trade between the ports of the Red Sea, Persian Gulf and the merchants’ base at Mundra, Mandvi and Cambay (Khambhat) in the region of present-day Gujarat.

Much before this 17th-century influx of Kutchi-speaking Hindu Bhatia and Muslim Memon, and Bohra and Khoja (the latter two are largely Shia communities) from Sindh, Kutch and Saurashtra, were the Gujarati- speaking Jain community who appear to be the earliest to establish itself in the Portuguese colonies of East Africa, namely the ports of Mombasa and Kilwa and Mozambique. Although the popular impression is that Jains are an austere community, their history in this region underscores that their success was in fact due to their adaptability to different milieus and mores, even endowing mosques in the medieval port cities of Gujarat, like Cambay and Bhadreshwar, for their fellow Arab and African traders (Mehta, Gujarati Business Communities in East African Diaspora 2001).

The migratory movement of Indians from Oman to the East African littoral region, especially its islands of Zanzibar and Pemba, was triggered after Omani Sultan Sayyid Said decided to shift his capital to Zanzibar from Oman between the years 1832 and 1840. This move was initiated on the advice of his trusted advisor, the Bhatia merchant Sewjee Topan (1764–1836). Many Indian traders were co-opted into the Sultan’s mission to have unrivalled control over the East African slave trade. Zanzibar and the Portuguese colony of Mozambique were both major slave marts in this region during the 18th and most part of the 19th centuries.

The East African slave trade was more a collaborative venture be- tween Indian traders and local Swahili-speaking merchants, who were a mix of Arab and African stock. It was the Swahili merchants who ventured into the interiors of the African mainland in search of slaves. Slaves then formed the bulk of the labour working in plantation economies like French Mauritius and Reunion islands. They were also used to transport ivory to the coast, as beasts of burden were vulnerable to attack by the deadly tsetse fly. It was the trading part – slaves and ivory – where Indian merchants were active in.

Indian traders as mentioned earlier were also involved in the lucrative export of gold, while imports included Indian cloth, spices, food grains, Chinese porcelain and silk. It is in this arch of the dhow trade – stretched from the East African coast and further east to Aden, Muscat and Hormuz, Gwadar, Sindh, before reaching the west coast of India and Bombay by the late 18th century – that the early seaborne circulations of manpower occurred.

Omani Bhatia: pioneers in linking Oman to India’s west coast

The Kutchi-speaking Hindu Bhatia merchant community from the princely kingdoms of Kutch and Kathiawar (like the Halai Bhatia) were among the first Gujarati trading communities to settle in large numbers in West Asia and East Africa. The famous Bhatia merchant Sewjee Topan encouraged other traders from his homeland, like the Bohra hardware merchant Budhabhoy Noormuhammed, to send his son Jivanjee (father of Karimjee, founder of the 196-year-old Karimjee Jivanjee Group, Tanzania) to Zanzibar in 1823. To date this family – now eight generations old in East Africa – and headquartered in Dar- es-Salaam (before that Zanzibar) since 1943 are the oldest franchisees for Toyota in Africa (Oonk 2009). This family till the Second World War had an office in Bombay’s Bruce Street (renamed Sir Homi Mody Street) to facilitate their business with the city.

The recruitment of manpower from the family and community pool to run and expand overseas businesses is the common narrative thread for Indian merchant settlements, with the exception of Japan where local staff was preferred. But for the Omani Bhatia the partnership with their Arab host was sweetened by religious tolerance. This understanding can be traced back to the 17th century, when the Arab rulers of Muscat, orthodox Ibadhi Sunni Muslims, allowed Gujarati Hindus to construct a Pushtimargi Vaishnav (Shreenathji Nathdwara or Krishna) temple in Muscat.

This was reiterated recently when the late Sultan Qaboos bin Saʻid wanted to extend his palace grounds. He offered a valuable location to the resident Omani Indians to build a new temple in place of two old ones. Muscat now has two temples: a new Shreenathji temple that houses two idols, and an old Shiva temple (Khimji 2015). This religious tolerance and partnership between Arab and Hindu traders historically stems from the important concerns of trade. Arabs had dominated the Indian Ocean trade since the advent of Islam in the 7th century AD. However, it was the Gujarati-speaking merchants’ acumen for numbers that made them indispensable to the Arabs.

According to Jaisinh Mariwala, the patriarch of the Mumbai-based Bhatia Mariwala family, the Bhatias have tremendous goodwill in Oman. Some established Bhatia families, like the Khimji Ramdas family, the Dharamsis and the Naranji Hirjee family, have been there for generations and are all citizens of Oman – Omani citizenship being hard to acquire. All these prominent Omani families historically have had a strong business presence in Bombay, but are known only in business and community circles, as they choose to remain low profile. The importance of these Omani citizens of Indian origin who are non-Muslim is underscored by the privilege they have been given – they are not subject to the Islamic Sharia Law in Oman. This emphasises how much the Sultan values their presence in Omani society.

In fact, the late Sultan Qaboos bin Saʻid’s cousin is married to the great-grandson of Khimji Ramdas, Ajitsinh Gokaldas Khimji.

An insight into how these old linkages work: many big Indian and foreign companies now have a presence in Oman through a resident Indian Omani. This includes the Shapoorji Pallonji conglomerate, who have built the Sultan’s palace in Muscat, Larsen & Toubro, the Tata Group and Dabur. With the exception of Dabur, all of them are headquartered at Bombay, demonstrating the continuing centrality of Bombay in spheres from infrastructure, construction, finance, banking and the traditional trading.

The Hindu Bhatia have maintained a distinct religious presence in Oman, while the old Memon and Khoja families have intermarried with the local Arabs because of a common religion. Families who returned from Zanzibar to settle in Oman mostly speak Swahili in addition to Arabic. However, the vital link among the Indian Khoja and the Bhatia communities is their language Kutchi, although the Khojas speak a variant of Kutchi called Khojki.

It was the ancestors of the old, established Omani Indian community that joined the entourage of Sultan Sayyid Said and his advisor Sewjee Topan to Zanzibar during the years 1832–1840. Although the Sultan signed anti-slavery treaties with the British, beginning as early as 1803, the slave trade from Zanzibar did not stop till the last treaty of 1873 was signed between Sultan Barghash and the British envoy, Bartle Frere, the much beloved former governor of Bombay. The demise of the Zanzibar slave trade resulted in the decline of this Island’s mercantile economy. What made business there still attractive was the triangular ivory trade, with Bombay port as its pivot.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House.

This an excerpt from the chapter titled ‘Migrants in the city and their overseas networks’ which appears in the book ‘Mercantile Bombay A Journey of Trade, Finance and Enterprise’.

This book is part of The Gateway House Guide to India in the 2020s. You can purchase the book here.