Over the past eighteen months, a degree of political ferment has been discernible in the ideological straight-jacket that regulates present day China. While the more extreme views – widely criticized domestically as reflecting Western thinking – continue to remain on the ineffectual outer fringes of Chinese society, other trends that deviate from the current mainstream political thought are beginning to assume significance.

Neither strikes a discordant note with the majority of Chinese who, having grown up in the People’s Republic of China and know only Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule, have a deep seated fear of laoduan, or chaos. For this overwhelming majority, as instilled by the Chinese Communist Party, the latter remains the guarantor of stability and, in the three recent decades, of economic prosperity.

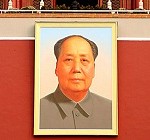

Veneration of Mao Zedong never really dissipated in China and has, in fact, shown an upward surge in recent years. From only 210,000 visitors to Mao’s birthplace in Shao Shan, Hunan, in 1980 soon after the end of the tumultuous Cultural Revolution decade, the number of visitors had risen by millions by the 1990s. Instances began to be reported of the release of pop songs using Mao’s lyrics like the ‘Red Sun’, which single sold over 6 million copies, and the erection of Mao Zedong’s statues in towns across China. Photographs of Mao proliferated with taxi drivers and farmers hanging them in cabs and homes. A wave of ‘Mao-era’ nostalgia became noticeable.

Neo-Maoist sentiment found resonance with the generation of Chinese born between the 1950s and 1970s who generally retain favourable memories of the Cultural Revolution decade (1965-75). The majority were ‘Red Guards’ and many suffered no physical harm. Most, including those who saw their parents penalized, later joined the CCP to advance careers or ensure security in the years ahead. Many are now entering China’s Party, government and military power elite. The influence of ‘pro-Mao’ sentiments was visible during the recent National People’s Congress (NPC) session in March.

The contents of at least 27 identified ‘neo-Maoist’ websites suggest that this nostalgia has been fuelled by diverse factors including rampant corruption, unchecked inflation, efforts by liberal economists to dismantle State owned Enterprises (SOEs), grabbing of arable lands of farmers by rural cadres, a widening gap between the rich and poor and, the perceived dilution of purist communist principles. In the run-up to the National People’s Congress (NPC) session held in March this year, these websites stepped up criticism of liberal personages including a couple of ‘princelings’ (privileged children or close relatives Communist Party honchos) but were not shut down although 3 million other websites were closed in the same period on various other charges. The suggestion of support from the Party’s Propaganda Department is strong.

Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) member in charge of Propaganda Li Changchun, and Director of the CCP Central Committee’s Propaganda Department, Liu Yunshan, retain a tight grip on the propaganda apparatus. They have not fought shy of subjecting even Premier Wen Jiabao and President Hu Jintao’s public utterances, made while travelling abroad, to censorship. Liu Yunshan is a candidate for elevation at the next Congress. Chen Kuiyuan, who is associated with the hardline ‘Left’ and is Vice Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Conference (CPPCC), attended an important Propaganda Department conference in January 2011. Li Changchun and Chen Kuiyuan joined the Party in 1965 and Liu Yunshan in 1971—all during the Cultural Revolution and the upward progression in their careers was uninterrupted throughout that decade.

Neo-Maoist sentiment, or ‘Red Revival’ as called by some, has elicited the tacit support of many ‘princelings.’ Some top cadres have tapped into this popular sentiment to shore personal credentials and possibly garner support of the Party’s ‘Cultural Revolution-era’ cadres who number over 30 million. Bo Xilai, a ‘Princeling’ (son of the late Bo Yibo–a Long March survivor, veteran senior Party cadre and friend of Deng Xiaoping) aspiring for elevation in 2012 to the Politburo Standing Committee, has launched a ‘Red revival’ campaign in his centrally-administered municipality of Chongqing. In January 2010, Chongqing approved inclusion of a Red Guard cemetery in the list of protected historical monuments and introduced ‘Red’ activities. Some PBSC members, including Xi Jinping, widely viewed as President Hu Jintao’s successor, have praised Bo Xilai’s ‘Red revival’ efforts. China’s Vice President and Military Commission Vice Chairman Xi Jinping, himself visited Mao’s former home in Shaoshan, Hunan, twice in the past six months. During his visit this past March, he praised the ‘spiritual legacy’ of Mao Zedong. Others like PBSC member and Security Czar, Zhao Yongkang and PBSC member Li Changchun, both due to retire at the next Congress in October 2012, have visited Chongqing and expressed support for Bo Yibo’s ‘Red’ movement. The Director of the powerful General Political Department (GPD) of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), Li Jinai, was another recent visitor.

Hinting at the strength of these ‘neo-Maoist’ sentiments some reports claimed that all but three of the seven PBSC members attended the lavish 90th anniversary celebrations of the Communist Party’s formation organized by Bo Yibo at Chongqing. Hu Jintao, Wen Jiabao and Li Keqiang stayed in Beijing along with the Director of the Party’s all-powerful Organisation Department, Li Yuanchao.

The tenor of Hu Jintao’s speech at the Party’s 90th anniversary appears to reflect the popularity of these sentiments. They are an acknowledgement of the influence of the over 30 million members who joined the Party during the Cultural Revolution and Party entrants born between 1960-70, or the hong er’dai. CCP Central Committee (CC) General Secretary Hu Jintao spent over 72 minutes reading out his 9,797-word carefully scripted speech where he recounted the successes achieved under the leadership of the Party, but also offered glimpses of potential future political tensions.

He dwelt, for instance, on the need for enhancing ‘socialist values’ and the ‘socialist spirit’ among Party cadres to bring them closer to the people. He warned that the challenges ahead are “more strenuous and pressing than at any point in the past.” Unlike on past occasions, this time Hu Jintao invoked Mao’s legacy. He referred more often to Mao Zedong and his contributions and to a lesser extent to Deng Xiaoping. Mao was mentioned five times while Deng merited only three mentions and Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao’s ‘scientific development concept’ mentioned even less. Hu Jintao pointedly referred to the ‘Four Cardinal Principles’, which though enunciated by Deng Xiaoping later became a buzzword of the ‘Left’. Hu’s speech paid unmistakable obeisance to Mao’s legacy and Mao Zedong Thought

Equally important and also reflecting more purist Marxist-Leninist-Mao Zedong thought is the emergence of the political thinking encapsuled in the comments of General Liu Yuan, Political Commissar of the PLA’s General Logistics Department. Tipped to soon enter the Central Military Commission, Liu Yuan was appointed full General in 2009 and is the son of former President Liu Shaoqi. At a conference in Beijing this May, attended by at least six other PLA Generals, he presented an essay, as part of a book, calling on China to rediscover its ‘military culture’ and asserted that ‘the Party has been repeatedly betrayed by General Secretaries, both in and outside the country, recently and in the past.’ The book advocated a ‘New Left’ to save China and the CCP. Liu Yuan is close to Vice President Xi Jinping, another ‘princeling’.

How long these differing trends of thought would be tolerated by senior

Party echelons is uncertain. Many emerging leaders are ‘princelings’ and have personally suffered, or witnessed the tragic suffering of their families, during the Cultural Revolution. Many remain unwavering in their loyalty to the Party, which they joined during the Cultural Revolution and see as vital for China’s rise, while a few venerate Mao’s legacy. They are most unlikely to allow neo-Maoist or other sentiments to become disruptive or derail reforms. Additionally, many of the Cultural Revolution entrants to the Party would be nearing retirement when their influence would diminish.

What does this potentially more purist ideology mean for India? For sure, India can expect a tougher, non-compromising stance by Beijing on issues perceived as affecting Chinese sovereignty and territorial issues – including those of the border. We are possibly entering a less flexible new era in Sino-Indian relations.

Jayadeva Ranade is a former Additional Secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2011 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.