On 5 October 2018 the U.S. announced the launch of the International Development Finance Agency, a government agency to support America’s private sector enterprises investing and operating abroad.

For a country that prides itself on private, market-based, independently-managed multinationals, the creation of a state-backed enterprise for supporting investments abroad is surprising, regressive even. But such is the economic ferocity with which China has moved with its state-led investments globally, that it has forced the U.S. to reassess and develop a new approach towards outward foreign investments.

Chinese state-owned enterprises now have a formidable global footprint, owning everything from natural resources to infrastructure to financial services. In 2017, China was the third largest source of outward FDI at $125 billion, behind only the U.S. ($342 billion) and Japan ($160 billion)[1].

For decades, major western powers such as the U.S., Europe and Japan have aligned their private sector foreign investments in strategic assets, such as natural resources, with their foreign policy objectives. This history can be traced back to the British and Dutch East India companies – and earlier. The developing countries, on the other hand, have been so fixated on attracting capital inward that an outbound investment was feared as loss of capital, let alone being considered strategic.

Now, however, with the rise of China as also other emerging powers such as India, there is a new recognition of the need for outward foreign direct investments (OFDI) that can be made for strategic interests.

‘Strategic OFDI’ can best be defined as that outward foreign direct investment where the source of funds is backed by the government of the investor country, the asset targeted is of national importance to the investee country, and the resulting investment has geoeconomic and geopolitical dividends for both.

The sources of such funding are sovereign wealth funds (e.g. Abu Dhabi Investment Authority), foreign exchange reserves (e.g. China’s State Administration for Foreign Exchange or SAFE), government banks (e.g. Japan Bank for International Cooperation) and select private multinationals (e.g. Blackrock). The most attractive strategic assets are natural resources (e.g. oil reserves, farmland), physical infrastructure (e.g. ports), and most recently, financial market infrastructure (e.g. stock exchanges).

A typical geopolitical dividend for such an investment will be access to sensitive sovereign assets such as ports and transnational road corridors. A typical geoeconomic dividend will be the ability to influence the economic policy and regulations of the target country.

Sovereign wealth funds are the most popularly known source of such funds. Altogether, the top 80 sovereign wealth funds in the world now hold over $8 trillion of capital[2] — a dramatic rise of 60% since 2008[3]. Norway’s wealth fund tops the global list with $1 trillion in assets, followed by China Investment Corporation at $941 billion and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) at $683 billion.

On paper, the mandate of sovereign wealth funds is to invest in global business opportunities that can provide a healthy return for the nation’s wealth. This requires smart diversification of investments across geographic regions and industry sectors. However, given that these funds belong to the state, most of the investment decisions are discretionary and often strategic in nature, and nations have long used these funds to secure geoeconomic and geopolitical returns.

Such funds were critical in bailing out American financial companies when the trans-Atlantic crisis began in 2007. ADIA invested $7.5 billion in Citigroup for a 4.9%[4] stake in 2007, becoming the bank’s largest shareholder[i]. The same year, China Investment Corporation invested in Morgan Stanley for a 9.9% stake[5]. In all, sovereign wealth funds are estimated to have invested a total of $60 billion to bail out western financial companies in 2007 alone![6]

China’s Strategic OFDI began with its goals to secure natural resources purely for a rising economy and to expand the market footprint of its products and services – very similar to the precedents set by the western powers. What caught the world’s attention was China’s use of Strategic OFDI for aid. Risk capital in the form of equity has been a key need for developing countries which otherwise only had access to concessional debt financing from multilateral institutions like the World Bank. By taking equity stakes in infrastructure projects that it is helping build in foreign countries, China is able to simultaneously provide aid and make strategic OFDI.

It has now expanded this strategy into its transnational Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese enterprises now have a global footprint in 117 countries, worth $1.9 trillion – which are increasingly being funded with equity[7]. For instance, since the launch of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in 2013, a Gateway House report reveals that Chinese equity investments in Pakistan are becoming common – from less than one investment then, to 20 today, or 13.5% of 148 projects examined.

China has smartly diversified its strategic OFDI strategy to banks. In 2007, state-owned Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) bought a 20% stake worth $5.5 billion in South Africa’s largest bank, Standard Bank (SB)[8]. This investment bought the Chinese government direct influence in the bank with two seats on the bank’s board, and access to the bank’s operations cross 20 African nations that depend on the bank for their development financing. No surprise that the joint venture sponsored the 2015 Focus on China-Africa Cooperation Summit at which 100 infrastructure projects worth $80 billion were initiated across 30 African countries[9]. Since then ICBC has also acquired majority stakes of banks in other countries, like Bank of East Asia, Standard Bank of Argentina and Tekstil Bank of Turkey.

But what has missed the world’s attention is China’s growing strategic OFDI in financial market infrastructure. In May 2018, a Chinese consortium comprising the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) bought 25% of the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) for $122 million. China even added a $37 million technical assistance package to sweeten the deal. Its bid was 50% higher than that of the closest competitor, the National Stock Exchange of India. This came close on the heels of an $87 billion[10] investment of the Pakistan Stock Exchange by a similar Chinese consortium in 2017, giving China a 30% stake in the institution.

These moves have critical geoeconomic implications. China can now push for the issuance of bonds in Bangladesh and Pakistan for funding Chinese infrastructure projects, enable cross-country listing securities with Chinese exchanges, launch yuan-denominated instruments, and even change regulations to deny the listing of companies from countries adverse to their China’s geopolitics.

It is surprising that India is not the natural choice for developing countries like Bangladesh to partner in financial market infrastructure. India has strong public and private players running market infrastructure and the Indian economy is similar to other developing countries. In fact, Indian firms like Financial Technologies, a private Indian company, have been early movers in building the infrastructure and buying equity stakes in foreign financial markets. Financial Technologies[ii] held a 60% stake in Bourse Africa (2008)[11], 51% stake in the Dubai Gold and Commodity Exchange (2005)[12], 100% of the Bahrain Financial Exchange (2011) and 100% of the Singapore Mercantile Exchange (2010)[13]. The Bombay Stock Exchange also welcomed a 5% stake by Germany’s Deustche Bourse in 2007 which eventually led to the BSE adopting the DB technology platform in 2013.

Like China, some Indian state companies have also been systematically expanding their strategic OFDI. A 2017 study by Gateway House shows that the foreign equity investments of India’s energy companies alone is now 70 projects spread across 25 countries[14].

In plain-outward FDI, the U.S. is the global leader. In 2017, the U.S. registered $346 billion in outward FDI. Its cumulative investments abroad have now crossed $7 trillion[15]. Since the majority of its investments are routed through holding companies in financial centres such as the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Caribbean Islands, Bermuda, and Singapore, it is difficult to assess the ultimate investee country and the assets targeted. The U.S. has energy multinationals like Exxon that is present in 38 countries and boasts a capital base of $18 billion[16]. And its investment banks such as Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch were the key underwriters (and initial equity holders) for foreign IPOs, including China’s largest companies such as PetroChina, Sinopec, China Mobile and Bank of China.

However, a report by the 2017 Congressional Research Service on outward FDI showed that more than 70% of investments were in the advanced economies of Europe, 96% of the total outward FDI was reinvested earnings, and majority of the investments were made to service the local markets in foreign countries. This means that American multinationals are not overt players in the strategic assets of developing countries.

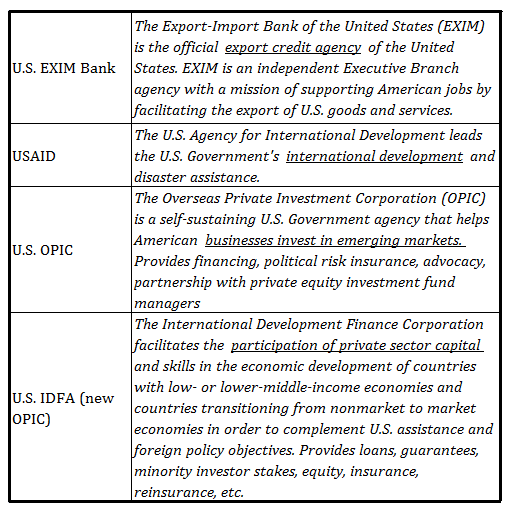

Nor are U.S. government agencies such as U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corp. (OPIC), U.S. Export-Import (EXIM) Bank , U.S. Development Credit Authority and USAID (aid agency) Enterprise Funds, which support outward investments, equipped to do so, being limited by their mandate and capital[iii]. The capital base of U.S. OPIC of $21.5 billion[17] and U.S. EXIM Bank of $24 billion[18] is Lilliputian compared to China EXIM Bank’s $344 billion[19].

For strategic OFDI, the U.S. seems to be relying on the Bretton Woods-era multilateral institutions, like the World Bank, to exert influence and direct financing.

Which is why the October 2018 launch of the International Development Finance Agency (IDFA) can be a game-changer. IDFA is slated to have a funding of $60 billion and the mandate to compete against Chinese and other foreign development finance institutions with equity financing rather than just debt financing and political risk insurance as is currently the case.

This change is visible in other major players like the $173-billion Japan Bank of International Cooperation (JBIC) that provides financing to Japanese multinational enterprises, and which has gradually upped its share of investment loans for enabling foreign equity investments from 40% to 70% since 2010[20].

As Strategic OFDI gains salience and permanence, it will invite deeper scrutiny than a simple commercial venture will merit. In February 2018, the U.S. securities regulator blocked China’s Chongqing Casin Group’s bid to acquire the Chicago Stock Exchange for $25 million, citing national security considerations. A bid by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) to acquire the American energy giant, UNOCAL, in 2005 and Dubai-backed DP World’s bid to acquire American ports, run by the British-firm P&O in 2006, were similarly blocked a decade ago.

To examine new bids by foreign entities in emerging and sensitive sectors such as private data and technology infrastructure the U.S. upgraded its national security legislation in August 2018 with the National Defense Authorization Act[21]. Canada, France, Germany and Japan have followed with similar legislations.

The competition for global assets as a strategic tool will intensify. The onus lies with governments to reconfigure their foreign policy to align with these developments.

Akshay Mathur is former Director, Research and Analysis & Fellow, Geoeconomic Studies, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

Footnotes

[i] In 2009, as Citigroup’s share price plummeted, ADIA sued Citigroup for losses. Arbitration proceedings that followed gave its decision in favour of Citigroup in 2017.

[ii] In 2013, Jignesh Shah, promoter of Financial Technologies was jailed for financial irregularities. FTs stake in DGCX was sold in 2016 and SMX was sold in 2013. Court proceedings are still underway.

[iii] US EXIM Bank is the official export credit agency, US OPIC is the official agency for American business investing in emerging markets, and US AID is the official foreign aid agency.

References

[1] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, World Investment Report 2018: Investments and New Industrial Policies, <https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2018_en.pdf>

[2] Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings, August 2018, <http://www.swfinstitute.org/sovereign-wealth-fund-rankings/>

[3] Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, What is a Sovereign Wealth Fund?, <http://www.swfinstitute.org/sovereign-wealth-fund/>

[4] Sidel, Robin, The Wall Street Journal, Abu Dhabi to Bolster Citigroup With $7.5 Billion Capital Infusion, 27 November 2007, <http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB119613039399104832>

[5] Merced, Michael J., and Keith Bradsher, The New York Times, Morgan Stanley to Sell Stake to China Amid Loss, 19 December 2007, <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/19/business/19cnd-morgan.html>

[6] Cohen, Benjamin J., ‘Sovereign Wealth Funds and National Security: The Great Tradeoff’, International Affairs, vol. 85, no. 4, 2009, pp. 713–731.

[7] American Enterprise Institute, China Global Investment Tracker, <https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/?ncid=txtlnkusaolp00000618>

[8] Olson, Parmy, Forbes, China Grabs A Slice Of Africa, 25 October 2007, <http://www.forbes.com/2007/10/25/standard-bank-icbc-markets-equity-cx_po_1025markets13.html>

[9] Standard Bank Group, Annual Integrated Report 2015, <http://reporting.standardbank.com/downloads/SBG_FY15_Annual%20integrated%20report.pdf>

[10] Pakistan American Business Association, Chinese Consortium Gets 40 percent Shares in Pakistan Stock Exchange, <https://pabausa.org/1259/chinese-consortium-gets-40-percent-shares-in-pakistan-stock-exchange/>

[11] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/financial-tech-buys-60-stake-in-bourse-africa/articleshow/3820833.cms

[12] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/financial-technologies-exits-dubai-gold-and-commodity-exchange-with-stake-sale-to-dmcc/articleshow/50760776.cms

[13] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/singapore-mercantile-exchange-begins-trading/articleshow/6466568.cms

[14] Bhandari, Amit, and Kunal Kulkarni, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, India’s global energy footprint, 14 February 2017, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/indias-global-energy-footprint/>

[15] Jackson, James K., Congressional Research Service, U.S. Direct Investment Abroad: Trends and

Current Issues, 29 June 2017, p. 2, <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RS21118.pdf>

[16] https://cdn.exxonmobil.com/~/media/global/files/summary-annual-report/2017-summary-annual-report.pdf

[17] https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/files/OPIC_Annual_Report_2016_web.pdf

[18] https://www.exim.gov/sites/default/files/reports/annual/EXIM-2016-Annual-Report.pdf

[19] http://english.eximbank.gov.cn/upload/accessory/20175/2017531315427099615.pdf

[20] Japan Bank for International Cooperation, JBIC Annual Report 2015, <http://www.jbic.go.jp/wp-content/uploads/page/2015/12/45003/2015E_01.pdf>

[21] Oleynik, Ronald A., Seth Stodder, Antonia I. Tzinova and Libby Bloxom, Mondaq, FIRRMA Expands CFIUS Jurisdiction In 2 Major Ways, 23 August 2018, <http://www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/x/730240/real+estate/FIRRMA+Expands+CFIUS+Jurisdiction+in+2+Major+Ways>