This article is the second in a two-part series. Click here to read the first part.

On March 1, after two years of careful intelligence-gathering, a major crackdown was made by EUROPOL[1] and Romanian Police on a key migrant smuggling network emanating from Romania and neighbouring Serbia – both EU countries. Two of the arrested smugglers were Indian residents in Romania and were suspected of leading the network’s recruitment branch with links to India, and to many more Indian recruiters believed to be dispersed in EU countries across Central and Eastern Europe. All these resident recruiters have links to parochial gangs who transport the migrants locally.[2]

The busting of one part of a major hub-and-spoke human smuggling network is of little comfort to either India or the UK which, on 4 May 2021, signed an agreement on expediting the repatriation of ‘irregular’ migrants from India, largely from Punjab and Haryana.[3] Unauthorized immigrants are troublesome for any host country. It deprives it of valuable taxes, creates stagnation in wages for certain jobs, and often the involvement of a few in crime has the effect of creating xenophobia in residential communities. Sadly, for these irregulars – many unskilled and semi-skilled – their precarious status often makes them victims of unscrupulous agents and puts them at the receiving end of extortion, violence and abuse, usually by overseas employers and landlords.

Though India can be justifiably proud of her successful British-Indian community of 1.6 million, it must also be remembered that the early roots of this diaspora lie not in its storied class – like the Hinduja brothers, Laxmi Mittal, Ugandan Indian Mayur Madhvani, or celebrated economist Lord Meghnad Desai; but rather in Indian sailors (known as lascars), soldiers (faujis) and labourers. This was the profile of most irregulars of the time, many of them being Sikh youth.

Just like today, it was this group of immigrant workers which, during the colonial period of the early 1800s, triggered the greatest angst amongst the host population: inter-mixing and inter-marriage with local girls. They filled a growing gap in the UK labour market, working for cheap wages and longer hours, thereby enabling London’s docks and shipping in the colonial past, to today’s ‘Mom-n-Pop’ stores, small retail outlets and restaurants, to be financially viable. The latter were largely established by the post-independence immigrants of the 1950s and 1960s.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Migration was natural two centuries ago. In 1814, the English East India Company was made responsible for their Asian-born lascars who worked seasonally in London’s docks while waiting for their ships to be repaired or refitted or loaded with a full cargo before they could sail home.[4] [5] This was the only interaction that the English had with coloured people from the Indian subcontinent, as there were more of them seeking their fortunes out in British India rather than Indians going to the UK, with the exception of the few Indians studying in British universities.

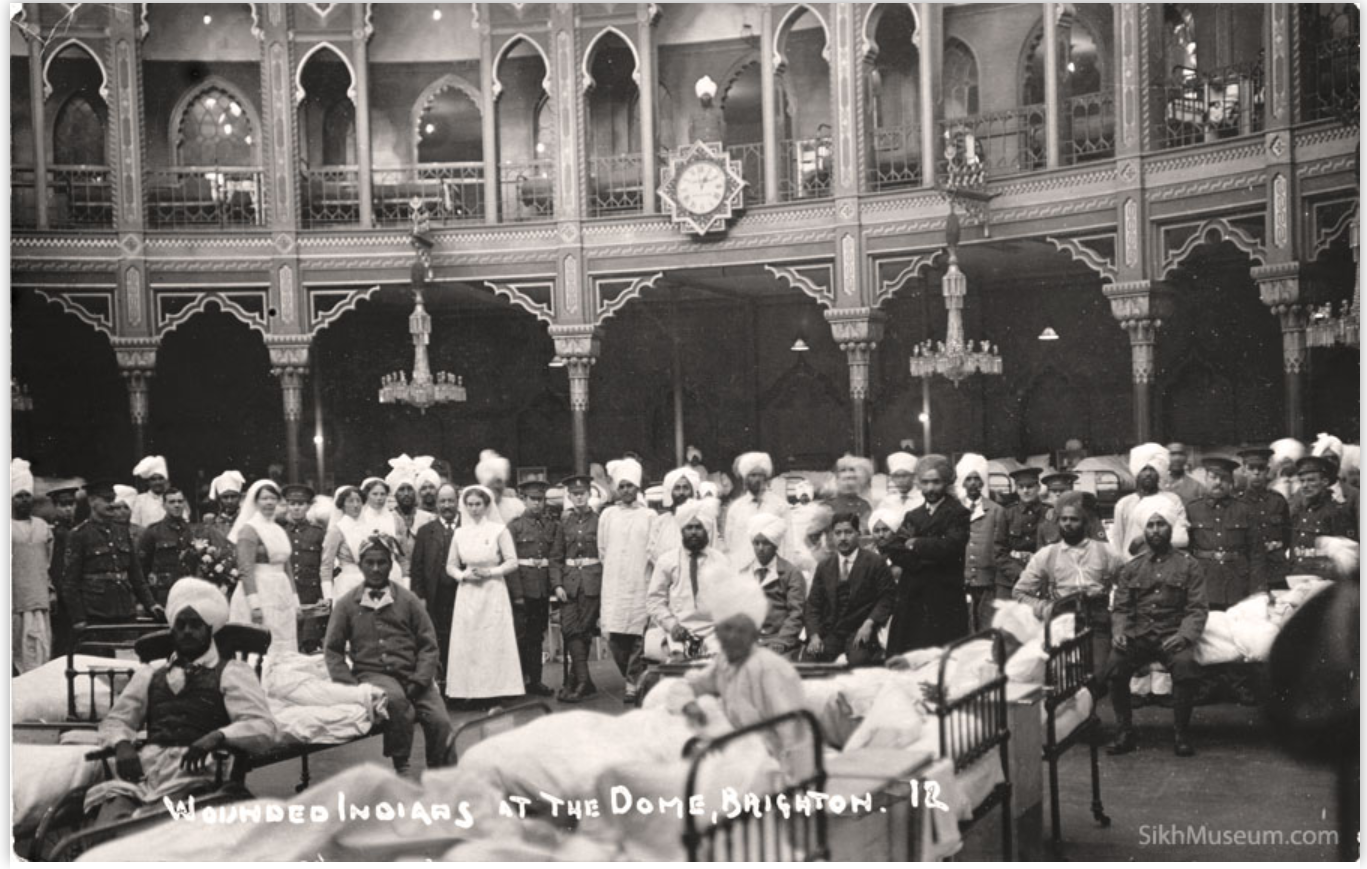

The First World War (1914-1918) saw a huge influx of British Indian regiments into Great Britain, many travelling from there to the Continent to fight alongside the Allied forces. Sikhs, designated a martial race by Victorian ethnologists,a made up 20% of the British Indian army during this period although they were less than 2% of British India’s population then.[6] Their experience of travelling and living as soldiers in the UK inspired a few early faujis and their families to immigrate. Britain already had in place its first immigration act, the Aliens Act of 1905, whose main criteria was the refusal of entry if immigrants could not demonstrate an ability to support themselves and their families.

Source: www.sikhmuseum.com

The inter-war years from 1918 to 1939 saw a sizeable inflow of migrants. One study[7] notes that “by 1939, almost every large (English) city seemed to have a small number of Sikh residents for the most part engaged in selling clothes in the markets”.[8]

The end of the Second World War saw migration from British colonies into the UK – and the return of the English back home as most colonies like India became independent soon after. Among the Commonwealth immigrants into Britain there were many Sikhs, who already had a tradition of travelling overseas as soldiers and a nascent network of resident kinsmen. Many who left were those uprooted from their homes in West Punjab due to India’s Partition. The pull factor for all was the demand for labour to reconstruct Britain after the Second World War. It was also Sikh family strategy then to send the youngest son overseas, whose earnings could add to family wealth from landholdings.

From 1950 to 1970 emigration from India into the UK peaked.[9] It coincided with a growing presence of Indians settling in Southall in west London, a fact that was noted when that town’s two cinemas were bought by Punjabi immigrants in late 1960s. This generation was largely successful.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Commonwealth Immigrants Bill (1961)[10] was the first of many barriers to this immigrant inflow from former British colonies. A ‘secondary’ immigration of East African Indians, many British passport holders, fleeing from the Africanization (nationalization) of Indian businesses in Kenya and Tanzania, had begun. It was followed by the expulsion of Indians in August 1972 by Uganda’s dictator Idi Amin, with thousands settling in England as they held British passports or under a newly introduced quota system.[11]

The 1990s were a tipping point for increased immigration from Punjab. The aftermath of the 1980s insurgency in Punjab saw immigration rise from this state to the UK due to unemployment at home, an established overseas community-and-family network, the continued market demand for labour in small restaurants, shops and manual work in the UK. In parallel was the proliferation of proactive travel agents who could ‘manage’ the logistics, border agencies and immigration checks, often with the help of international human smuggling networks. Thus, the migration corridor of ‘irregulars’ was established.

By the early 2000s, with unemployment rates on the rise, this ‘craze to go abroad’ extended to the state of Haryana. Recently, the youth of Himachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir have added to the migration stream. Blending into the line of migrants to the UK are other subcontinental nationalities like Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, an added complication for both Indian and UK officials.

The dangers are acute for those who choose to be smuggled in[12] as evidenced by the March 1 raids by EUROPOL, which succeeded in blocking 30 irregulars from crossing borders within the EU.[13] However, the migration flow from India is unlikely to mitigate, especially with lack of a modern agriculture industry in Punjab and other northern states. Moreover, there is no stigma attached to being an ‘irregular’ back home, or shame in being repatriated. It’s a full-time pursuit. Many of those sent back either try to re-enter the UK or attempt another destination. The rewards for the tenacious far outweigh the risks they undertake. Unlike the early post-independent immigrants, the desperation of these young men to succeed is heightened by the debts undertaken by their families to sponsor their journey overseas.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House.

This article was written under the aegis of The Gateway House-FLAME Policy Lab at FLAME University, Pune.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2021 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] The abbreviation EUROPOL stands for European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation.

[2] EUROPOL news report 2 March 2021 “Gang smuggling Indian nationals busted in Romania”. URL: https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/gang-smuggling-indian-nationals-busted-in-romania

[3] Transatlantic Council on Migration, Donkey Flights: Illegal Immigration from the Punjab to the United Kingdom (Washington D.C., Migration Policy Institute, 2014), p.2. URL: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/BadActors-DonkeyFlights-FINALWEB.pdf Also, see United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Smuggling of Migrants from India to Europe particularly the UK: A Study on Punjab and Haryana (New Delhi, UNODC, 2009). URL: https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Smuggling_of_Migrants_from_India_to_Europe_-_Punjab_Haryana.pdf

[4] Lascar is a reference to any South Asian sailor. They are known to have traveled to and from London as early as the 17th C. Many worked on English East India Company (EEIC) ships, and were in demand not just by the EEIC but other European companies, as the mortality rate was lower among them compared to Europeans – given the arduous voyage from the Subcontinent to London or the Continent, and back. Most were on three-year contracts and were an exploited class – in terms of their living conditions both on land and at sea, pay and long hours.

[5] Another class of Indian workers who were visible in London were Indian ayahs (nursemaids) who often accompanied visiting or British families with young children returning home to Great Britain.

[6] SOAS University of London, “Empire Faith and War: The Sikhs and World Was One”, <> https://www.soas.ac.uk/gallery/efw/>

[7] Richard T. Shaefer, ‘Indians In Great Britain’ International Review of Modern Sociology, Volume 6 (Autumn), 1976. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41420610?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A11ddd1fb3d54df2e376a03744ee3e75f&seq=19#page_scan_tab_contents

[8] See Shaefer, p. 310.

[9] See Shaefer, p 310. In 1951, the Indian population in Great Britain was 30,800 or 41% of total coloured population, i.e., those from other Commonwealth countries. By 1961, 250,000 Indians resided in England & Wales of whom 81% had been born overseas, and by 1971, the Indian population rose to 483,000 or 38% of immigrants from Commonwealth nations.

[10] The 1961 Act was soon followed by Immigration from the Commonwealth Act (1965) and one in 1971, which introduced the one-year work permit that could be renewed only if an application is made to relevant authorities by the employer.

[11] Many East African Indians also immigrated to the United States and Canada. Some, especially the older people, preferred to return to their home villages, towns or cities in India. Ahmedabad has a special residential society built by East African Indian.

[12] Most irregular migrants are those who enter legally but become irregular later, like rejected asylum seekers, visa and work permit overstayers.

[13] https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/BadActors-DonkeyFlights-FINALWEB.pdf