This article is the first in a two-part series.

The H-shaped island of Bombay earned the moniker A ilha da boa vida (the island of good life) amongst Portuguese sailors and naval officers in the 16th century because the Island never failed in pleasing them during their brief stopovers. There was plentiful game hunting for recreation, food, sweet water, and rest for the tired crew. This was particularly so in 1529 when Portuguese Captain Heitor da Silva led the Portuguese naval fleet in sea battles with the navy of Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat and his allies in the waters off Bombay.[1]

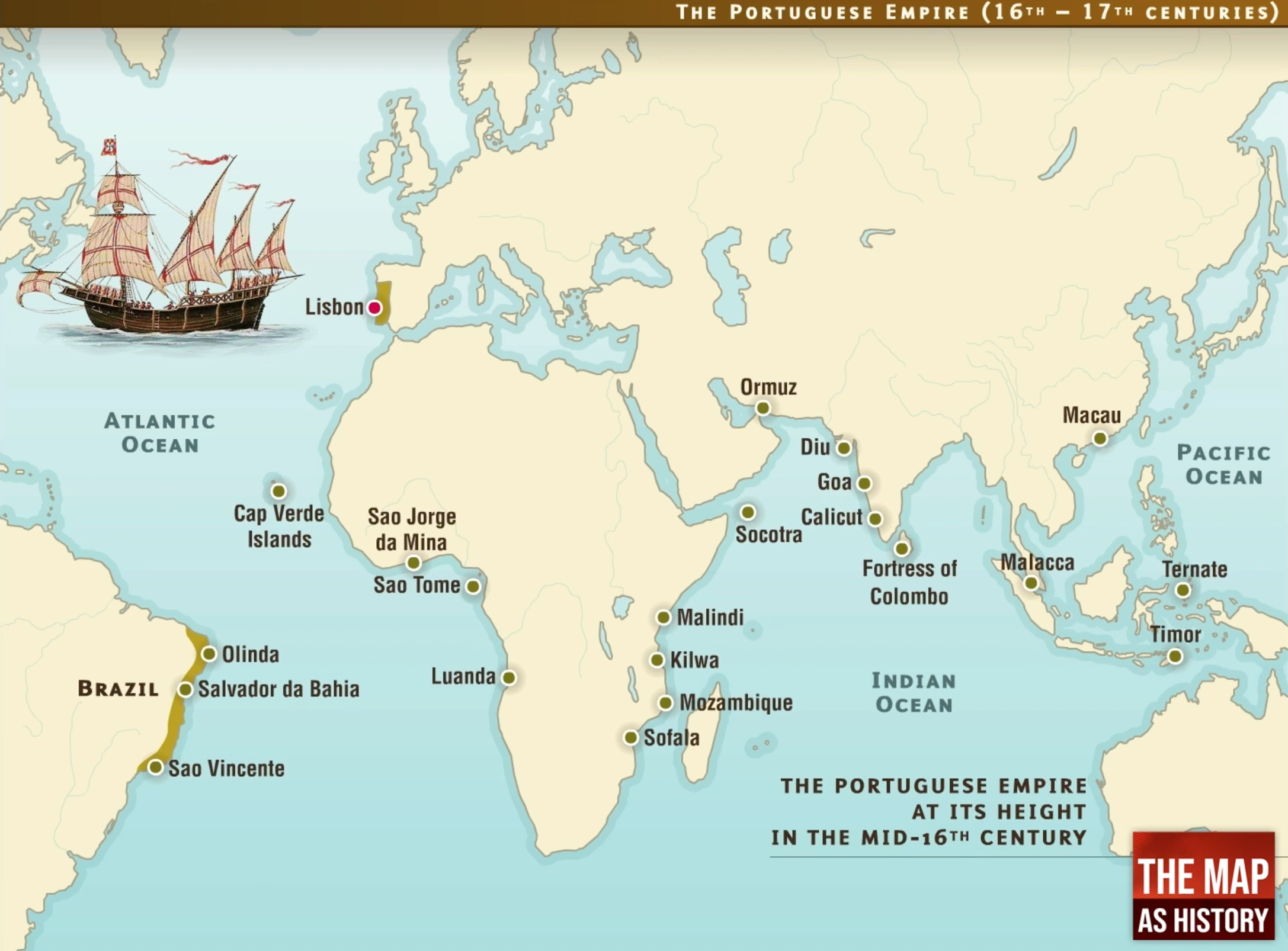

Bombay’s natural harbour provided a safe anchorage for the Portuguese fleet to retire to during these conflicts, but the islands did not merit their attention except for recreation, as it wasn’t a pre-existing port like their other acquisitions were – Mombasa, Hormuz, Goa and, later, Malacca (See Map 1). The Portuguese were instead focused on acquiring the more strategic port of Diu which controlled the maritime trade to the ports of the Gulf of Khambhat (a source of cotton piece goods) and the entire western seaboard of India.[2]

Courtesy: https://www.the-map-as-history.com/

Merchant shipping in this early modern period did not undertake transoceanic crossings. Most ships were unsuited for it and the profitability of the intra-coastal trade made transoceanic trade unattractive. But Diu, with its strategically located port, was a gateway to the pepper coast of the Malabar in south west India and beyond to South East Asia and the Far East. It was the reason the Portuguese persisted in the 15th century to discover a direct sea route to India. This was accomplished by Vasco da Gama when he arrived in Calicut with his ships in 1498. The goal was to break the five centuries old Venetian monopoly as suppliers of spices to the Continent[3] so that “all European nations would seek their spices from Lisbon”.[4]

It was the enormous profits of the spice trade – pepper from the Malabar coast, cinnamon from Ceylon, ginger, nutmeg, mace and cloves from South East Asia – that emboldened a small Iberian nation of just 1.4 million (in 1540) to forcibly break into an established network of Indian Ocean trading communities.[5]

The Portuguese wanted all key ports along the Indian Ocean littoral – just like China’s maritime Belt and Road Initiative desires today – in order to fully divert the spice trade from its final destination: Venice.

Venice[6] was a key distributor in Europe for goods arriving from the East. It was a network predicated on age-old collaborations between them and Mamluk Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, Arabs from the Gulf, the Safavids of Persia, coastal Indian and South East Asian kingdoms, like Calicut and Malacca, which the Portuguese tried to break into at the turn of the 16th century through force (superior artillery, cannons and warships – the nifty Caravels) and sometimes diplomacy.

Courtesy: The British Museum

They succeeded in the early 16th century – temporarily. The slump in the Venice trade from 1501-1506 when compared with normal supplies in 1496-98 makes this self-evident. Venetian exports of spices from Alexandria, sourced from the East and South East Asia, collapsed to less than a third (pepper was just 135 ton as compared to 480-630 ton three years earlier) and from Beirut, a key port for the Levant trade where spices arrived overland here from Persian Gulf ports like Basra, to just one sixth (10 ton compared to 90-240 ton).[7][8]

But in spite of controlling ports across the entire littoral of the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese failed in making their seaborne empire a profitable commercial enterprise in the long term – at least for its Crown.

Great powers everywhere have flaws, and the Portuguese were no exception.

They financially over-extended themselves, with capital expenditure exceeding their revenue through trade, the Cartaz (a pass for transiting through their territorial seas), customs, tribute and land. The Estado da India[9] (State of India) was too far away and spread out. In 1640, the Portuguese had 26 coastal ports across the Indian Ocean – after having lost many to the Omani Arabs, the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and closer home Bassein (Vasai) and Salsette to the Marathas. By 1670 it was down to 16.[10]

Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Portugal was a small nation with limited manpower to send overseas. It was already thinly spread from East Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, South East Asia, coastal China, West Africa and Brazil (See Map 1). Internal conflicts arose, with private Portuguese traders and later missionary enterprises[11] (after 1540) often trumping the interests of the Portuguese imperial enterprise in the East.

These inherent weaknesses became evident when they came up against the other European companies in the Indian Ocean, in particular the powerful Dutch East India Company in the 17th century. The Dutch captured the Portuguese strongholds of Colombo and Cochin. It was in this grand global geopolitical game that then Portuguese Bombay Islands played a small but significant role.

The Portuguese held Bombay for 127 years, when the very same foe – Sultan Bahadur Shah – who the Portuguese battled in 1520s, turned into an ally. He gifted his new ally in his fight against the Mughals in Delhi, the extensive Province of the North[12] which included Bombay islands, in 1534. Diu was gifted the next year.

It is well-known that the islands were the first British royal possession in the east, as they were gifted as a dower in 1661 by Portugal’s King John IV[13] on the marriage of his daughter Catherine da Braganza to England’s Charles II. The year coincided with a period when the Portuguese in Asia were under tremendous military pressure from the Dutch. The coming together of the House of Braganza with Great Britain’s House of Stuart through marriage, had a virtuous fallout. Portuguese India was saved from extinction by strong French and English diplomatic pressure on the Dutch after the royal marriage. This induced the Dutch to make peace with Portugal in 1661-63.

By then, however, the Portuguese seaborne empire was in irreversible decline in spite of the hard infrastructure they built across littoral Asia, much like China’s Belt and Road has built today. Caught up as the Portuguese were in their initial successes, they soon realized that building is separate from the difficult task of maintaining effective control and ensuring profitability.

Symbolically, the Estado da India, established in 1505, ended when the Indian Navy and armed forces took over its capital city of Goa in December 1961.

The lesson from the Portuguese experience for China’s string of pearls (Colombo, Gwadar, Djibouti ports) – which also double up as strategic naval ports – is this: aggression never pays. Nor does bankrupting allies through expensive loans for port development which ultimately result in the takeover of the host nation’s territory.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2021 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References:

[1] Edwardes, S.M., The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island, Vol, 2 (Bombay, Gazetteer Department, Government of Maharashtra, Reprint 1977), p. 28.

[2] Diu also secured the sea lanes for the supplies of essentials like rice, to Goa, the capital city of the Portuguese Estado da India. Goa in its early years was a key port for the supply of horses (from the Gulf region) and gold (from its port of Sofala, East Africa) to the Vijayanagar empire in the Deccan.

[3] The Italian city-state of Venice was the main outlet for the sale of spices in Europe. However, the Venetian enterprise was a collaborative one, involving Mamluk Egypt, the Ottomans, key coastal kingdoms like Calicut and Malacca.

[4] Subrahmanyam, Sanjay, The Portuguese Empire In Asia 1500-1700: A Political And Economic History (London, The Orient Group UK Ltd., 1993) p XX

[5] These traders comprised Arabs, Armenians, Jews, Persians, Gujarati and Kutchi Banias and Bohra, South Indian Mapilla and Chetty traders, Indonesian and Chinese traders, who owed their allegiance to their host kingdoms and traditional carriers – Arab seafarers- of their goods. The Portuguese were viewed as outsiders.

[6] In the 10th century both Venice and Genoa began to prosper through trade in the Levant. A bitter rivalry developed between the two, which culminated in the naval battle of Chioggia (1378–81), where Venice defeated Genoa and secured a monopoly of trade in the Middle East for the next century. Venice made exorbitant profits by trading spices with buyer-distributors from northern and western Europe.

[7] Wake, C.H.H., ‘The volume of European spice imports at the beginning at the beginning of and end of the fifteenth century’, Journal of European Economic History, 1986,Vol. XV, p. 633. Also, Subrahmanyam, Sanjay, The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700: A Political and Economic History (London and New York, Longman Group UK Ltd., 1993), p.66.

[8] Ibid. The export of other spices from Alexandria and Beirut too fell. Only 200 ton for 1501-1506 as compared to 580-730 ton (1496-98) from Alexandria, and just 35 ton (1501-1506) compared to 150-180 ton (1496-98) from Beirut.

[9] The Estado da India (1505-1961) was the name the Portuguese gave to that part of their empire which stretched from India to East Asia. In its widest sense, the name includes all Portuguese colonies east of the Cape of Good Hope and so, at its height in the 16th century, the Estado da India stretched from East Africa to Japan.

[10] Boxer, C.R., Portuguese India in the Mid-Seventeenth Century (Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1980), pp. 2-3.

[11] Catholic Missions like the Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinians, sustained themselves through trade and rents, in order to finance their work and institutions.

[12] The capital city of the Portuguese Province of the North was Bassein (today’s Vasai).

[13] He became the first Braganza king through a court revolt that overturned 60 years of Spanish Castilian rule in Portugal.