April 2019 marks the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Islamic Republic of Iran, barely two months after the Iranian Revolution shook the status quo — the Iranian rulers, West Asia, the whole world. Forty years ago, any mention of Iran – or Persia, as many still called it – brought to mind cats, carpets and crude oil. The Cold War was at its height, and Iran was a country firmly within the West’s purview, allied to the United States and other countries through economic, political and military alliances.

Today, that exotic picture has given way to one of a country of fanatical people, hell-bent on confrontation with the West, a member of the original trio, with North Korea and Iraq, whom Bush designated “the Axis of Evil”, the world’s “greatest exporter of terrorism” and a “rogue state” that has achieved “nuclear weapons breakout capability”.[1]

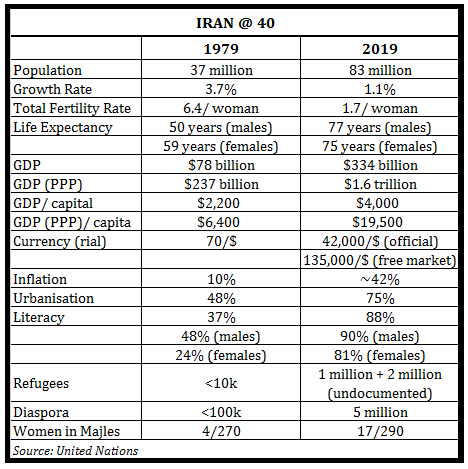

Such appellations do not convey the momentous changes that have taken place in Iran since 1979, some of it for the better, much of it for worse. Many contradictions lie beneath the apparent stability, a stability that is likely to stay while the Supreme Leader is alive. But tensions persist, such as those between religious mandate and technocracy; between tradition and youth, with its demands for a more modern way of life: nearly 50 million Iranians have no first-hand experience of the uprising that overthrew the Shah. Before the Revolution, a secular dictator ruled over a largely traditional people; today, a religious autocracy rules over an increasingly secularised population.

Politically, the Islamic Republic replaced a sham one-party constitutional monarchy. Even when there had been elections in the 1950s and 1960s, these were rigged, not bona fide expressions of the people’s will. Within this new theocracy, political authority flowed from the religious.

Since the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, the former Supreme Leader, in 1989, those in Iranian politics have been trying to lay claim to his legacy and stay true to his ideology just as after Lenin’s death, all future Soviet leaders claimed they were his heirs.

The current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has occupied the post for 30 years, is a purist who believes that any concession on the Revolution’s hard line could bring about a collapse of the entire system, as happened in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. The Supreme Leader is not only the head of state, but the highest-ranking political and religious authority in Iran.

Relating to the outside world

How does such power translate to external relations? One of the early slogans of the Revolution was, “Neither East, nor West, but the Islamic Republic”, and Iran firmly rejected alliances with the two major Cold War powers, the U.S. and the Soviet Union. But the taking of the American hostages by radical students in 1979 and the near-decade-long Iran-Iraq War left Iran isolated on the world stage, impelling it to reorient its foreign policy objectives and take a more pragmatic approach to neighbours and others. From wanting to export Islamic ideology, it now sought to consolidate its legitimacy at home. After the first Gulf War, and especially after the election of the reformist President Khatami in 1997, Iran developed much more constructive diplomatic relations with other states, especially with Europe, Russia and China.

Under Khatami’s successor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran’s foreign policy took on a much more ideological and populist stance. President Ahmadinejad’s second term, following a highly dubious re-election in 2009, not only caused widespread domestic protests and international criticism, but also coincided with the events of the Arab Spring and the bloody conflict in Syria.

Iran is now trying to build and maintain a so-called Shi’ite Crescent by exerting its influence and building alliances with Iraq, President Assad’s Syria, the Hezbollah, the Shi’a Islamist political party and militant group based in Lebanon, and the large Shia minorities of Yemen, Afghanistan and Turkey. Today, Iran acts as a regional (super)power, whereas before the Revolution it was only a first among equals.

State of the economy

At home, though, the Iranian regime has faced economic sanctions of one kind or another since the very early days of the Revolution, and over the years, these have taken a heavy toll on the country’s economy and people.

Since its nuclear programme became public in 2002, the UN and individual countries have imposed tough sanctions on it to try to prevent it from developing a military nuclear capability, the existence of which it vehemently denies.

In 2006, negotiations began with the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, Germany and the European Union to assure the world powers that Iran would not develop nuclear weapons.

When an agreement was eventually signed in 2015, the sanctions were partially lifted. But when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, the U.S. unilaterally withdrew from the nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions, hoping to force Iran to change its policies, including its support for regional militant groups. President Rouhani’s election win in 2013 led to a general mood of optimism as the country’s economic conditions improved, leading to his re-election in 2017, but his second term has been dogged by the fall-out of the U.S.’ withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and increased sanctions.

The economic impact thus far has been severe, with the Iranian economy contracting and expected to continue doing so by up to 4% in 2019, according to the IMF.[2] The Iranian currency (the Rial) has lost two-thirds of its value and inflation stands at 40%. Yet, the lowest strata of society has benefited greatly: access to basics, such as water, electricity, housing, healthcare and education, is nearly universal.

Tensions of the present

Many Iranians, while supportive of the regime, are increasingly frustrated by the economic, political and social constraints placed on them. There is some discontent in the country against the multi-billion- dollar cost of the continued support for President Assad’s Syria; the country’s pariah status worldwide; and the lack of civil liberties (especially for women), but the people are not inclined towards another bloody uprising — even if the U.S. may think otherwise.

In 2009, there were massive, nationwide, anti-government protests against the results of the 10th Presidential elections, which people regarded as deeply flawed. The “Green Movement”,[3] as it was called, was perceived then as the biggest threat to the regime since the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988. Protests erupted again after the events of the Arab Spring in 2011, though not on the same scale as before.

One act of civil disobedience, now termed the “Girls of Enghelab Street”,[4] had a young woman remove her mandatory hijab (white headscarf) in the middle of a demonstration in central Tehran, tie it to a stick and wave it at the crowd like a flag.

The treatment of women and the regime’s disregard of human rights remains deplorable. Earlier this week, Nasrin Sotoudeh, a prominent lawyer who dedicated her life to defending women’s rights and speaking out against the death penalty, was sentenced to a total of 38 years in jail and 148 lashes.[5]

The right to peaceful assembly is frequently violated and arbitrary arrests are an everyday occurrence. The country executes hundreds annually, and while this number has declined, some have also been executed for crimes they allegedly committed as children.

The regime is well-entrenched and faces no imminent external threats. Rather, the internal tensions within the ruling autocracy and its ability to fulfil the expectations of an ever-demanding populace will eventually decide whether it survives or falls.

Nader Fekri is Visiting Professor of Politics at Mumbai University.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] These are direct quotes from the U.S. State Department that have been in use since President Bush’s State of the Union speech in 2002.

[2] World Economic Outlook, October 2018, p. 41 <https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2018/October/English/main-report/Text.ashx>

[3] BBC News, ‘Ahmadinejad defiant on ‘free’ Iran poll’, 14 June 2009, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/8099115.stm>

[4] BBC News, ‘Iran’s hijab protests: The Girls of Revolution Street’, 5 February 2018, <https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-middle-east-42954970/iran-s-hijab-protests-the-girls-of-revolution-street>

[5] The Guardian, ‘Human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh jailed ‘for 38 years’ in Iran’, 11 March 2019,

<https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/11/human-rights-lawyer-nasrin-sotoudeh-jailed-for-38-years-in-iran>