The combined market capitalisation of the five Big Tech companies Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and Google (FAAMG) in September 2020 was over $6 trillion,[1] more than double the GDP of India.

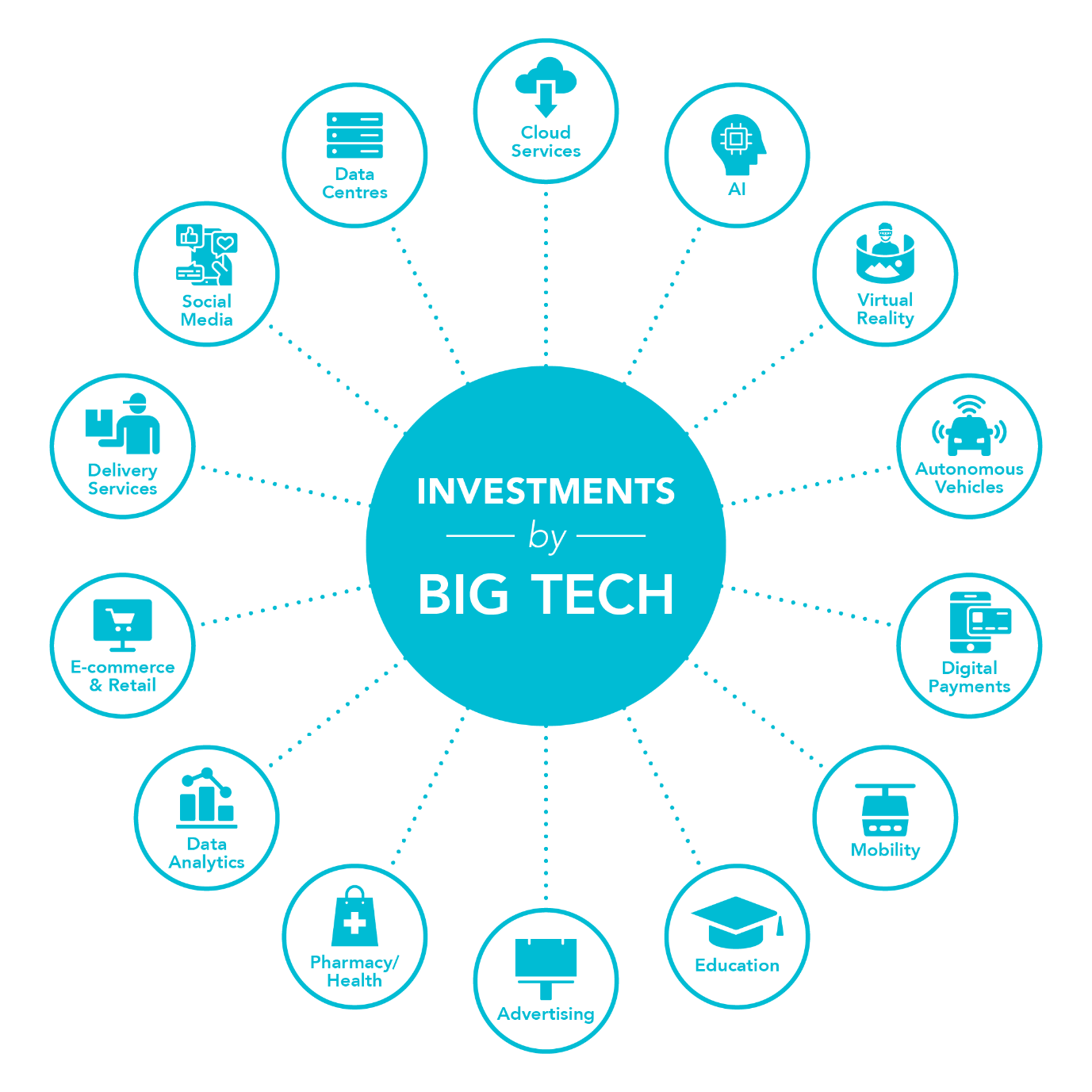

This staggering data point raises a fundamental question: what makes the big tech companies ‘big’? Three things: first, continuous investments across domains and sectors from e-commerce, digital payments to AI and autonomous vehicles; second, zero financial cost to users of the platform (excluding the cost of data, an evolving concept for users); three, network effects i.e., a phenomenon where every new user adds value to the big tech platform.

There’s nothing reprehensible about being big and established. But it is the ‘how’ of their dazzling growth that has red-flagged concerns about Big Tech. The world over, FAAMG companies have come under increased scrutiny for reasons ranging from monopolistic behaviour to data privacy to content moderation to advertising policies. In India, the most recent case against Big Tech was due to the amended (now suspended) Whatsapp privacy policy which allowed the platform to share metadata with its parent company, Facebook.[2] Australia introduced a media bargaining code[3] in December 2020 to curb anti-competitive practices by Big Tech by mandating a payment structure between the platform and news outlets. In the U.S., where there is a long history of anti-trust cases against tech and other giants, the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law concluded after an investigation in October 2020, that the Big Tech companies have been indulging in anti-competitive practices by abusing their status as gatekeepers of the internet.[4]

Mergers and acquisitions by Big Tech across sectors have been key to their burgeoning growth. In the COVID-19-hit year of 2020 itself, Salesforce acquired six companies,[5] Facebook acquired over seven companies including Kustomer, a customer service start-up, for $1 billion,[6] and Apple focussed its 2020 acquisitions on AI technology companies.

The infographic below provides a pictorial representation of the reach of the big tech companies, that indicates their power and ability to influence society, economy and even politics.

In the last few years, governments around the world have questioned some of these investments alleging that their objective is to neutralise competition, leading to monopolisation and stifling of innovation. In December 2020, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission along with 48 U.S. States filed a case against Facebook alleging monopolisation and killing of competition by making large acquisitions including that of Instagram in 2012 for $1 billion and Whatsapp in 2014 for $19 billion.[7]

The U.S. Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Google in October 2020, alleging monopolistic practices in search advertising and anti-competitive practices by entering contracts with smartphone makers requiring they make Google their default search engine.[8]

Europe has moved heavily against Google in the recent past. The European Commission, in 2019, imposed a penalty of over $1 billion (approximately 1.3% of its annual turnover in 2018) on Google for abusing its dominant position in online advertising.[9] Google was found guilty of including anti-competitive clauses in contracts with its vendors, restricting them from hosting rivals’ content. In the past, Google has been subjected to similar fines by the European Commission, to the tune of over $6 billion, for abusing its dominance.

Amazon has been accused, in the U.S., of using the data of third-party sellers for furthering its own retail business on the platform[10] – a formal lawsuit is expected soon. The company has faced similar claims of misuse of third-party data, harming the smaller players, for its own benefit in Canada and the EU, in 2020.[11] The European Commission has even started a separate investigation to assess if Amazon gives preferential treatment to its own products. [12]

China is playing catch up too with its homegrown BAT (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent). In December 2020, China’s anti-trust regulator alleged that Alibaba, the country’s largest e-commerce company, violated the anti-monopoly law by entering into contracts that demanded exclusivity from vendors.[13] More recently, in March 2021, Tencent was fined $ 76,000 for not being transparent about its acquisitions.

While in the US, it is the Department of Justice, Federal Trade Commission and the states that are leading the anti-trust cases, and the European Commission in Europe, in India it is the Competition Commission of India (CCI). As he primary anti-trust watch dog, Competition Commission of India, in January 2020, launched an investigation into Amazon and Flipkart for abusing their dominant positions and carrying out acquisitions (such as the Walmart-Flipkart deal) with the aim to stifle competition and for using predatory pricing tactics. The companies have managed to obtain a stay on the CCI investigation from the Karnataka High Court.[14] In October 2020, CCI started a probe against Google for pre-installation of G-pay on Android phones and for forcing exclusivity for in-app purchases.[15] In another case in 2018, CCI imposed a penalty of $20 million on Google for abusing its dominant market position and for bias in search activities on the internet.[16]

In India, the primary legislation dealing with anti-trust is the Competition Act, 2002. The purpose of this law is to protect the industry and consumers from monopolistic behaviour that leads to abuse of dominance, predatory pricing or denying market access to rival or smaller players. In addition, the law also mandates ‘merger control’ which means that a merger transaction will require the prior approval of CCI if the deal crosses stipulated financial thresholds.[17] But, to cater to the all-pervasive tech sector, the Act needs updating as several transactions escape its scrutiny.

The Indian government is trying to update its regulation to deal with fast-moving Big Tech. In order to control unfettered investments in India, and to curb monopolisation in the e-commerce sector in particular, the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade introduced amendments to the Foreign Direct Investment Policy in 2018. This imposed embargoes on product exclusivity and prohibited inventory-based models for foreign e-commerce players.[18] Of course Flipkart and Amazon protested – but they did have to change their business models to align with the new regulations. In spite of such policy measures, companies continue to hold dominant market positions.

Globally, as the anti-trust movement against Big Tech gathers steam, it is time to find solid solutions. Breaking-up the Big Tech companies is not a sustainable long-term solution as this will merely open the door for a new set of dominant players – just as Blackberry and Yahoo were replaced by FAAMG. Governments must look at solutions that create a level playing field, a fair marketplace and promote consumer welfare as well as innovation in the industry.

One such solution is stricter control, in addition to the financial thresholds, by a nation’s anti-trust watchdog prior to a merger or acquisition which will entail a detailed investigation including a comprehensive due diligence into a potential transaction by the regulator.

In India in particular, as the government seeks to promote the use and adoption of technology across sectors, it must first adopt a whole-of-government approach. This is important especially as the issues in the technology sector including data, privacy, investments and anti-trust are all inter-linked and impossible to segregate. The technology sector will benefit immensely if the policy makers across ministries align and expedite policy-making – from Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology on data protection (personal and non-personal data) and AI, to Ministry of Commerce and Industry on e-commerce and FDI, to Ministry of Home Affairs on national security concerns, to the Competition Commission of India on anti-trust and merger control. This inter-ministerial collaboration can reap immense socio-economic benefits for the Indian economy, resulting in policies that reflect the New India.

Ambika Khanna is Senior Researcher, International Law Studies Programme, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2021 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckjones/2020/09/26/the-faamg-stocks-drive-the-markets/?sh=2c5eba495439

[2] https://www.whatsapp.com/legal/updates/privacy-policy/?lang=en

[3] https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r6652

[4] https://judiciary.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=3429

[5] https://hicglobalsolutions.com/blog/list-of-salesforces-acquisitions-in-2020-an-year-for-salesforce/

[6] https://about.fb.com/news/2020/11/kustomer-to-join-facebook/

[7] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2020/12/ftc-sues-facebook-illegal-monopolization

[8] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-monopolist-google-violating-antitrust-laws

[9] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_1770

[10] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-22/amazon-amzn-apple-aapl-could-be-next-for-antitrust-lawsuits

[11] https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/14/amazon-faces-antitrust-probe-in-canada.html

[12] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/pl/ip_19_4291

[13] https://techcrunch.com/2020/12/23/alibaba-antitrust-probe/

[14] https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/amazon-flipkart-probe-sc-declines-to-entertain-cci-plea-to-remove-karnataka-high-court-stay/article32946397.ece#

[15] https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/07-of-2020.pdf

[16] https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/07%20%26%20%2030%20of%202012.pdf

[17] Section 5 and 6 of the Competition Act, 2002.