This is the third in a four-part series on Partition. Read the next one here.

Read the first one here and the second one here.

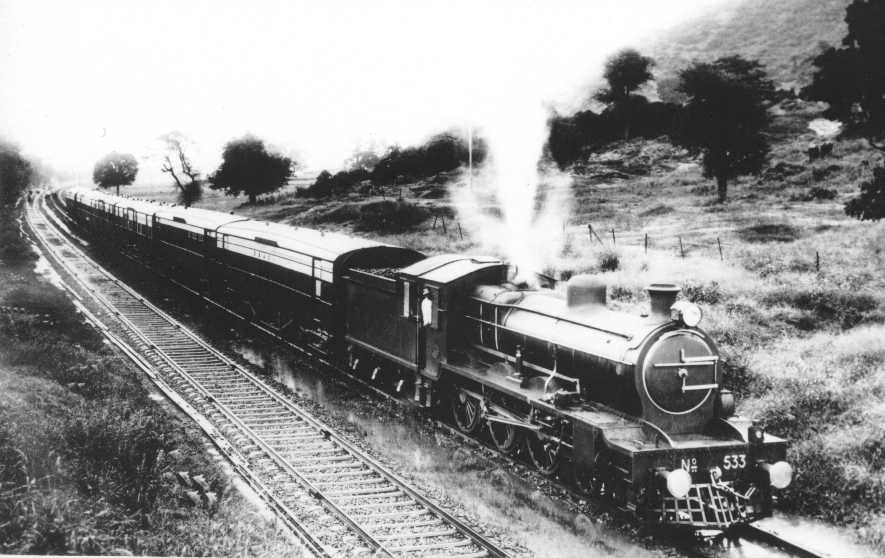

The majority of the Sikhs and Punjabis who made the abandoned military barracks of Sion-Koliwada Camp (renamed Guru Tegh Bahadur Nagar), Mumbai, their home hailed from the hilly tracts of NWFP, district Hazara, specifically, and its three tehsils or administrative divisions, namely, Haripur, Mansehra and Abbottabad. This area is now part of Pakistan and was renamed Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2010. They came directly to Bombay – having no relatives in East Punjab or Delhi – on BB&CI Railways’[1] famous train, the Frontier Mail. The train, renowned for its punctuality and astonishing speed, covered the distance of 2,335 km from Peshawar station to the BB&CI terminus at Bombay Central in 72 hours.[2]

“Military trucks came in the middle of the night to collect everyone (non-Muslims) from Fuljriyan village, Hazara District.[3] The entire community, my mother included, left the same night just before Partition, as riots had already begun in the Punjab,”[4] recalls Manmohan Singh, secretary, Sri Guru Singh Sabha, Dadar, widely known as the Dadar Gurdwara. They took refuge en route in Gurdwara Panja Saheb (in Hasan Abdal, 48 km from Rawalpindi), one of the holiest of Sikh shrines, that is even said to have a boulder sporting Guru Nanak Dev’s handprint or panja.[5]

From here, the refugees proceeded to Hasan Abdal station to board the Frontier Mail, with the option to either proceed directly to Bombay or take another train to Kashmir, where many NWFP Punjabis had relatives. Sikh, and Punjabi Hindu residents of the predominantly Pashtun speaking NWFP region, which lies close to Kashmir, had originally settled here in the wake of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s annexation of these territories. At the height of his rule, the Sikh Empire extended from the Khyber Pass in the northwest to the Sutlej River in the east, and from the Kashmir region in the north to the Thar Desert in the south.[6]

Along with these refugees from Hazara district, there arrived in Bombay a large community of Punjabis from Peshawar, located on the eastern end of the Khyber Pass and close to the Afghan border. Refugees from West Punjab (which became part of Pakistan) appear to have arrived in the city only after living for short periods in East Punjab, Delhi, Dehradun (Uttarakhand), Jagadhri (Haryana), Kashmir, and Ahmedabad, all of which have sizeable Punjabi populations even today.

Starting out in Bombay

Old-timers of GTB Nagar[7] recount how when they first arrived in Bombay, langar (or food from the community kitchen) was being served in the city’s first gurdwara, the Sri Guru Singh Sabha, said to have been established in 1919[8] on Dockyard Road (Shahid Bhagat Singh Road). It housed many refugee families. Punjabi Sikh and Sindhi refugees also lived in shanties along Dockyard Road, where a traditional langar of black dal, rice, roti, sabzi (vegetables) and sometimes a sweet, would be served to the hundreds who assembled. By all accounts there were about 10,000 refugees, mostly Punjabi Sikhs, who occupied the barracks at the Koliwada Camp.

The concept of sharing food went hand in hand with charity. According to one interviewee, “The reason why Punjabis have large bodies is because they house a large heart.” During emergencies, like the 26/11/ 2008 terror attack, the Dadar Gurdwara provided food at site for the Mumbai police and commandos. Closely located as it is to the Tata Memorial Hospital, it also offers lodgings to numerous outstation cancer patients for a nominal fee.

Sharing food – besides the attendant camaraderie of the Punjabis – is how their repertoire of dishes became a staple in restaurants across Bombay, even those not run by them. The famed Langar Dal, the recipe for which has since figured in almost every well regarded Indian cookbook, had its humble origins in these community kitchens.

What may be better known, though, is the Fish Koliwada[9], created by Bahadur Singh, owner of Mini Punjab (Koliwada), one of the early Punjabi restaurants in the city. Other dishes that are evergreen on restaurant menus, are Tandoori Chicken, Naan, Dal Bukhara, Baingan (eggplant) Bharta, and many versions of paneer (cottage cheese).

Restaurateuring apart, in the early days, most refugees began earning a livelihood by hawking peppermints on trains, or became coolies, peons, and by the early 1950s, drivers of taxis and trucks. They attribute their success to support from already established community businesses, such as Mangaldas Verma, after whom Bombay’s Mangaldas Cloth Market is named, which helped many Punjabis get a foothold in the city’s cloth trade.

Similarly, Mangatram & Sons, Ishardas & Sons, and Dewanchand Ramcharan, were in the trucking business, or as one interviewee put it, “Sab tyre ke chakkar mein lag gaye” (everyone became involved in the automobile business), which included automobile spare parts and tyre shops, petrol pumps, and taxis.

Quite in opposition to these low-key, physically demanding professions, the flamboyant Punjabi personality found expression in the city’s Hindi film industry, with a string of actors, from the 1940s onwards (or even earlier, if one includes pre-Partition stars, like Prithviraj Kapoor), such as Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand, Sunil Dutt, Rajesh Khanna, and Dharmendra.[10] Among the prominent film directors are, Ramanand Sagar (of the tele-series, Ramayana) and Baldev Raj Chopra (of the tele-series Mahabharata).

Another facet of Punjabi culture that stands out is the Bhangra dance, and from the NWFP came the Gumbhar dance, whose beat is slower, but just as feisty.

So, as the fourth generation descendants of refugees from the former NWFP and Punjab grow up in the city they call home, they should not forget the Partition stories passed down to them and the pioneers who adapted – and also changed Bombay.

Sifra Lentin is Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House.

This is the third in a four-part series on Partition. Read the next one here. Read the first one here and the second one here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] The abbreviation BB& CI stands for ‘Bombay, Baroda & Central India’ railways. It is today’s Western Railways, whose headquarter is located opposite Churchgate Station. Today, the Frontier Mail, renamed the Golden Temple Mail runs from Mumbai’s Bombay Central Station to Amritsar Station.

[2] S, Shankar, ‘Classic Trains of India: Frontier (Golden Temple) Mail’, Indian Railways Fan Club, <http://www.irfca.org/~shankie/famoustrains/famtrainfrontier.htm> (Accessed on 30 August 2017)

[3] The British divided Hazara District into three Tehsils and annexed it to the Punjab. In 1901, when the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) was formed, Hazara was separated from Punjab and made a part of NWFP.

[4] According to historians Ian Talbot and Gurharpal Singh, “The precipitating event which triggered the violence in Punjab was the resignation on 2 March 1947 of the cross-community coalition government led by the Unionist PM Khizr Hayat Khan Tiwana. The Muslim League’s six-week agitation from 24 January 1947, ostensibly in the name of civil liberties, but in reality, to unseat the Unionist administration heightened communal tension in the Punjab’s twin cities of Lahore and Amritsar.”

Talbot, Ian, and Gurharpal Singh, The Partition of India (Delhi, Cambridge University Press, Reprint 2013), p. 75.

[5] Gurdwara Panja Saheb, Sindhi Wiki, <http://www.sikhiwiki.org/index.php/Gurdwara_Panja_Sahib> (Accessed on 30 August 2017)

[6] Singh, Khushwant, ‘Ranjit Singh’, Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ranjit-Singh-Sikh-maharaja> (Accessed on 30 August 2017)

[7] The author interviewed Nanak Chand Alag, Sardar Harcharan Singh Ratti, and Sardar Manmohan Singh, who is secretary of the Sri Guru Singh Sabha, Mumbai, a trust that runs the Dadar and C.S.T. (V.T.) gurdwaras in the city. She also spoke to Ishwar Lal Uppal at Hazara Society, Chunabatti. The non-GTB refugees spoken to were Romesh Sethi of Cuffe Parade and Sumitra Sethi of Marine Drive. The interviews took place over three days from 25 to 27 August, 2017.

[8] The earliest written record of the C.S.T. Gurdwara is 1919, therefore its centenary will be celebrated in 2019.

[9] Fish is not a staple food among Punjabis, but having settled in an island city and in the midst of a fishing village (lit. Koli wada translates to village of the Kolis, who are largely fishermen), they adapted the abundantly available local fish to their taste, thus Fish Koliwada was created.

[10] Other famous actors in the Hindi film industry are Manmohan Krishan, Madan Puri, Amrish Puri and Vinod Khanna.