Global growth was the main issue in focus for world leaders in the run up to the G20 Summit in Hangzhou in early September- why it has become weaker and more fragile than expected, and is falling short of the 2014 Brisbane Summit’s target of raising global growth by an additional 2 percentage points by 2018.

The differences between expectations and outcomes are wider for emerging market countries; the sustained shortfalls in growth have had a direct effect on living standards and inequalities in advanced countries and in emerging markets. China—today the largest country in purchasing power parity terms—has become among the main subjects of the growth uncertainties. The global context has clear implications for India’s growth, which remains the fastest among major countries, and its ability to sustain it.—

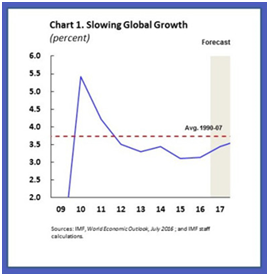

Let’s start by looking at the evidence on the state of the global economy. The reality is that global growth in 2016 is now projected at just over 3 percent (Chart 1)—below the outcome in 2014 and below expectations a year ago.

The repeated downward revisions to growth in recent years have reflected more the growth fundamentals, namely the capacity to grow sustainably (potential output), rather than cyclical factors.[1] Both advanced and emerging market countries have experienced successive declines in potential output and its growth rate: in the developed countries, the slowdown began before the financial crisis, and in the case of emerging markets, since the financial crisis.[2]

In both sets of countries, the leading cause has been lower efficiency of resource use, or total factor productivity (TFP) growth, likely resulting from rising misallocation of low-cost capital. The latest projections of potential output growth, for both sets of countries, for 2015-2020, are generally well below those made during the pre-crisis period (2003-2008), and for 2010-2014. The last quarter’s growth numbers for the United States signalled its third consecutive quarter of falling productivity despite improving employment.

The Hangzhou Summit committed to a Hangzhou Action Plan to address these challenges, nationally and multilaterally, and also build the resilience of the international financial architecture through strengthening the global financial safety net. Their importance is heightened by the expected rise in the Federal Reserve’s policy rate later this year and its implications for global capital flows, and the impact on countries with high corporate debt. Since the Hangzhou Summit, discussions have continued globally in the run up to the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings this week.

It helps that the G20 has recognised that central banks and monetary policy have been fully stretched, especially in the advanced countries. The emphasis now is rightly on taking coordinated steps to build the growth fundamentals through broadening structural reforms at national and multilateral levels: these have lagged since the Brisbane Summit.

At the national level, the Hangzhou Action Plan elevated the importance of additional public investment and necessary infrastructure in countries where there is sufficient fiscal space, especially in advanced countries, such as the United States and Germany, and in some emerging market countries. This will help demand support as well as potentially boost the recovery of productivity growth. However, in doing so, recent evidence from China confirms that infrastructure investment needs to be carefully selected and managed to boost growth.[3][4]

Beyond this, for many advanced countries and emerging markets, there are legacy debt issues from the financial crisis that have persisted and are constraining bank lending for infrastructure and growth. At the national and regional levels, (especially for the European Union), these debt issues need to be urgently addressed to nurture bank lending, private investment and innovation in more efficient sectors, and help reverse the overall trend of falling productivity.

Among emerging markets, and in China, in particular, this includes the interlinked problems of heavily leveraged financial and corporate sectors, from the rapid rise in corporate debt and real estate-related firms (close to 150 percent of GDP in China). As a result, in many emerging market countries, we are seeing weakening fundamentals in corporate balance sheets that are translating into rising bank vulnerabilities that will constrain bank financing for growth until fully addressed.

In India, too, stress tests of corporate and banking vulnerabilities confirm the risks from its high corporate leverage and the potential need to recapitalise state banks. It is important for the G20 to recognise that these fault lines have also resulted from the external spillovers from the unconventional monetary policies of many countries, especially in advanced ones.

In looking ahead to the priorities for public funding and growth, the Hangzhou Summit emphasised the interlinked roles of green financing and building sustainable infrastructure as the way forward toward eradicating poverty. Certainly, as emerging markets grow and urbanise, there will be rising demand for carbon consumption and urban infrastructure, and the communique stressed the need to ensure greater compliance with green standards in building urban infrastructure.

Imminent ratification of the Paris Agreement on climate change, helped by India’s support this week, is a major victory for multilateralism. Now, the international financial system needs to respond by building financial policies and regulations that attract private capital to help in the transition to a lower carbon global economy.[5] In this context, China’s interest in becoming a global leader in infrastructure, in part through its Belt and Road Initiative, will also be tested in its financing support for global climate action.

Among needed structural reforms, the Action Plan rightly pressed the need to reinvigorate global trade, recognising the rising political drive against globalisation in many countries. The weakness in global trade has also been elevated in the agenda for this week’s IMF/World Bank Annual Meetings.

The reality is that, in recent years, global trade growth has been weaker than global GDP growth, partly reflecting subdued global investment. But rising protectionism is another likely factor. The trade slowdown has curbed a key growth engine for the global economy, [6] and the impact has been especially severe in Asia since 2011. The Action Plan emphasised the room to reduce trade costs and eliminate temporary trade barriers. Although digital/ICT trade flows are surging, their impact on productivity has yet to be experienced, and the WTO needs to play a more central role in managing distortions to trade in services that could be of rising importance.[7]

The Hangzhou Action Plan broadened the overall policy focus by including additional commitments to promote inclusive growth, thereby recognising rising inequalities and the political attention they deserve. The communique elevated innovation as a new driver of growth, assuring developing countries special support in crossing their higher digital divide, especially through skills training and investments in education and health, and promising greater openness to surging digital flows. However, in this context, much more global attention and investment is needed for cyber security, which is of growing concern, especially in Asia.

The G20 also underlined in the communique the need to build the resilience of the global financial safety net, and broaden the use of the SDR: discussions on this issue have continued in the run up to the IMF Annual Meetings. However, it has become apparent that fundamental reforms of the IMF are not expected at this time and, as such, the focus is on ensuring its ability to attract bilateral borrowing agreements to build its lending capacity, at least until the next (17th) quota review can take place (expected by the 2017 Annual Meetings), and building greater cooperation with regional financing arrangements, such as the Chiang Mai Initiative.

Meanwhile, the Renminbi has become the fifth currency in the SDR basket of currencies, and there is certainly room to broaden the use of SDRs by central banks and other existing holders, to meet global liquidity needs.

The G20 has made wider and more specific commitments than in previous Summits, and the urgency of building global policy consensus to take them forward is greater than in the past. However, we are not there yet as coordinated structural reforms in key areas are still awaited to help reverse the ongoing “new normal” of mediocre global growth.

Anoop Singh is Distinguished Fellow, Geoeconomics Studies at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2016 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

Reference

[1] ‘Where are we heading? Perpectives on potential output’ in International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook (2015) <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/pdf/c3.pdf>

[2] Cette, Gilbert, John G. Fernald, Benoit Mojon, “Working Paper 2016-08: The Pre-Great Recession Slowdown in Productivity”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2016, <http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/wp2016-08.pdf>

[3] Atif Ansar, Bent Flyvbjerg, Alexander Budzier, and Daniel Lunn, ‘Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic fragility?’ Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 2016 , 360-390

[4] China still needs much more infrastructure investment per capita, but its rising investment was concentrated in less productive sectors such as real estate, and implemented by state owned enterprises (SOEs) that built excessive capacity in upstream sectors, such as coal, cement, steel.

[5] It helps that the Financial Stability Board has set up a task force on climate disclosure to advise how financial rules need to incorporate climate factors in pricing risk and financial assets.

[6] ‘Global Trade: what’s behind the slowdown’ in International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook (2016), <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/pdf/c2.pdf>

[7] Singh, Anoop, ‘Digital trade: new frontier’, International Center For Trade And Sustainable Development, 4 August 2016, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/re-energizing-global-trade-growth-new-frontiers-of-digital-trade/>