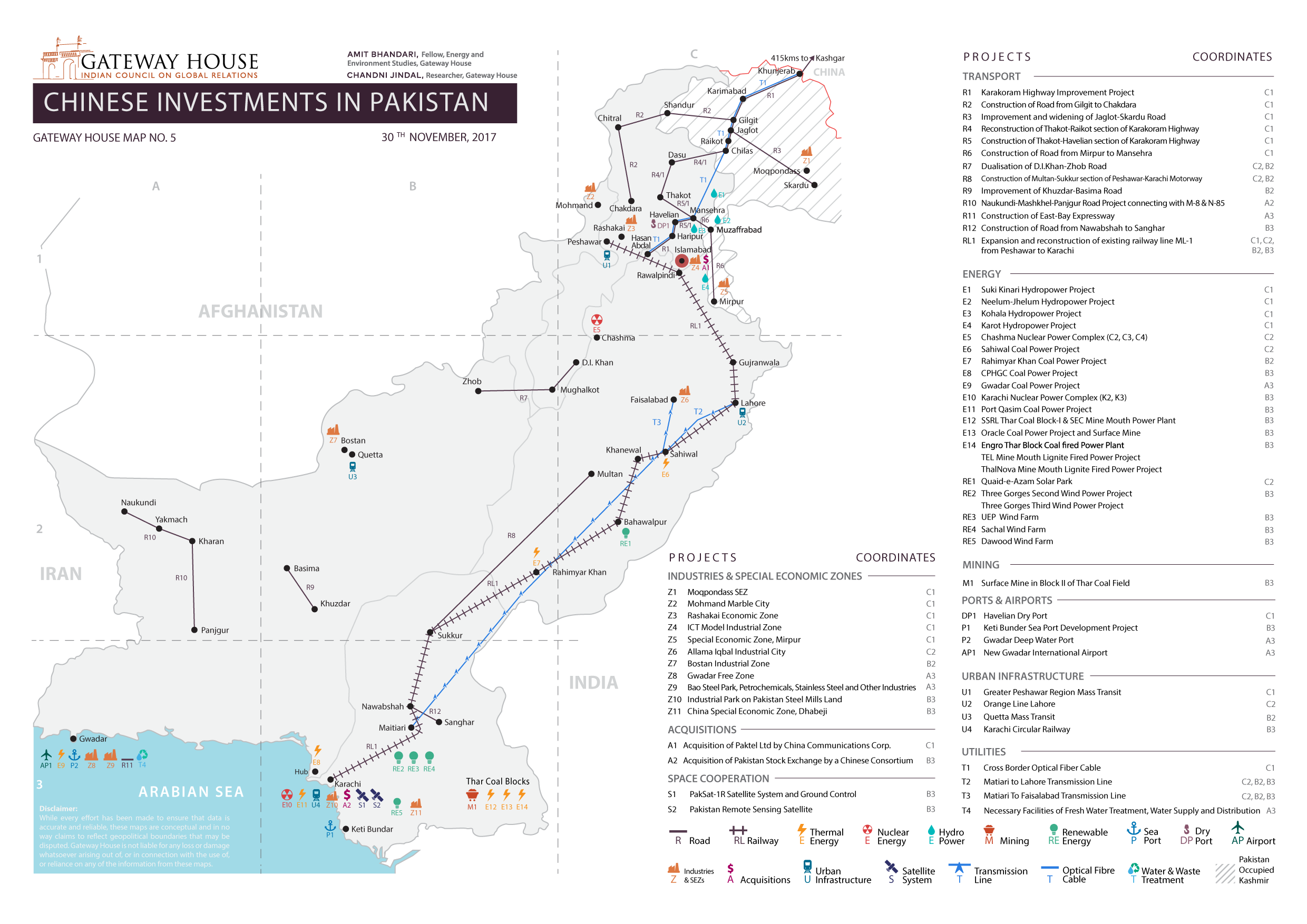

China’s total investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is pegged at $62 billion[1]. Detailed statistics are available for projects worth $42.6 billion, of which the power sector commands the largest portion, followed by roads, rail and urban infrastructure. So far, projects worth $2.3 billion have been completed and ones valued at $18.4 billion are under execution (November 2017). Some additional projects, such as nuclear power plants, which do not fall under CPEC, represent another $10 billion in Chinese investment.

While China touts the corridor as the flagship project of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and as a bid by President Xi Jinping to strengthen China-Pakistan ties, the economic logic for the spending is shaky. But its strategic implications are clear: The investments will facilitate the Chinese military presence in Pakistan and the Arabian Sea, where they can menace India’s oil and gas imports. It also will give China and Pakistan an opportunity to play a greater role in Afghanistan and Central Asia; this, too, could hurt India’s long-term long term strategic and economic interests.

Strategic, Not Economic Goals

For Pakistan, Chinese interest and investment could not have come at a better time. With the U.S. reducing its aid and thus relinquishing its role as Pakistan’s leading financial backer, China has moved to back its strategic relationship with Pakistan with big money. The benefits have already started to accrue to Pakistan. During 2016-17, Pakistan’s economy grew faster than it has for a decade, and the pace is expected to continue in 2017-18 as well[2].

However, CPEC is not a one-way ticket to prosperity for Pakistan. The project has downsides that will not be immediately apparent.

Proposed power sector investments illustrate the risks. They account for more than half of Chinese investment in Pakistan, and will add 60% to Pakistan’s existing power generation capacity. Pakistan needs power, but this volume will be difficult for Pakistan to absorb or export. The cost per megawatt of these projects is higher than similar projects in India. The expensive capacity will worsen the financial crisis in Pakistan’s power sector, leaving it highly indebted.

Most obviously, economically questionable investments appear to include propping up a flailing ally that is unable to keep pace with India, one of China’s major long-term rivals. They also could enable it to control a strategic port in the Arabian Sea. China, as the lender, can end up controlling the projects it has built and collecting revenues from them – as it has done for the Hambantota Port. But the diplomatic uses of its financial leverage over the Pakistani government could be priceless to China.

Food Security

A third motivation may be to secure food supplies for China, which is short of cultivable land. The Pakistani newspaper, Dawn, reported in June 2017 that the CPEC master plan[3], which hasn’t been publicly disclosed except in truncated form[4], envisages demonstration farms running into thousands of acres, food processing units and cold chains (systems for delivering refrigerated goods) in Pakistan. Islamabad has denied these claims, but its National Food Security Policy alludes to CPEC in relation to increasing agricultural cooperation between China and Pakistan[5]. China has a shortage of agricultural land and has been purchasing large parcels of it across the world in places such as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Mozambique and Ukraine. Agricultural cooperation under CPEC could be an extension of China’s food security policy.

Concerns for India

The CPEC presents challenges to India’s sovereignty, energy security and regional influence.

Sovereignty: The Karakoram Highway passes through Gilgit-Baltistan, which is Indian territory under illegal Pakistani occupation. Gilgit-Baltistan’s population is primarily Shia and already marginalised in Pakistan. It looks favourably on India, whereas the rest of Pakistan is Sunni-dominated and less friendly. Better connectivity allows Pakistan to change the demographic balance of the region, as China has done in Tibet and Xinjiang; that, in turn, enables it to incorporate Gilgit-Baltistan as a fifth province after a ‘referendum,’ permanently altering India-Pakistan relations.

Energy security: Gwadar Port, at the western edge of Pakistan’s troubled state of Balochistan, has no economic viability as an energy conduit or as a hub for exporting Chinese goods because of the sheer distance from China’s economic and consumption centres. But China may find Gwadar’s strategic location worth its $1.2 billion investment. Gwadar sits at the mouth of the Gulf of Oman, from where one-quarter of the world’s crude oil passes, including 65% of India’s oil imports. The port has natural value to China as a military base.

Regional influence: China is already the leading arms supplier to Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Since the military is an important power centre in all these countries, close ties to them give China a vote in their governance and policymaking. Along with being the leading investor in Pakistan, Myanmar and Sri Lanka, this allows China to make rules favouring its own companies to the detriment of India’s $20 billion trade with other SAARC nations.

This map is part of a larger book on Chinese Investments in India’s Neighbourhood. To see the project description and place an order for the book, please click here.

Amit Bhandari is Fellow, Energy and Environment Studies at Gateway House

Chandni Jindal is Researcher at Gateway House

Visualized and mapped by Debarpan Das

This map was exclusively developed by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Siddiqui, Salman, ‘CPEC investment pushed from $bbb to $62b’, Tribune, 12 April 2017, <https://tribune.com.pk/story/1381733/cpec-investment-pushed-55b-62b/>

[2] The World Bank, Pakistan to Record Highest Growth Rate in Nine Years: WB Report, (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2017), <http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2017/05/19/pakistan-to-record-highest-growth-rate-in-nine-years-wb-report>

[3] Husain, Khurram, ‘Exclusive: CPEC master plan revealed’, Dawn, 21 June 2017, <https://www.dawn.com/news/1333101>

[4] Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform, Government of Pakistan, Long Term Plan for China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (2017-2030), (Islamabad: Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform), <http://cpec.gov.pk/long-term-plan-cpec>

[5]Ministry of National Food Security and Research, Government of Pakistan, National Food Security Policy, (Islamabad: Ministry of National Food Security and Research, 2017), <http://www.mnfsr.gov.pk/userfiles1/file/19%20Revised%20Food%20Security%20Policy%2011%20September%202017.pdf>